Cooking with Linux - Serious Cool, Sysadmin Style!

So, mon ami, I've granted your wish, and you've had lots of time to show me the packages you've chosen for today's menu. Let's see what you've come up with. But François, there are literally hundreds of choices here! It would take forever to load, configure and test all these packages. I must admit, you've made some excellent choices, but we can't possibly cover all these things. Don't fret. There may yet be a way, but we'll need the help of another great package to do this right. Good guess, mon ami, that is exactly what I am talking about. Quoi? Oh, I see. You have that one on your list as well. Perhaps you do, but I may show you a side of things you hadn't thought about.

Quickly, François! Put that list aside and get ready. Our guests will be here momentarily. In fact, I see them coming to the door now.

Welcome, everyone, to Chez Marcel, not only one of the world's great restaurants, but also a special dining experience where great open-source software meets great wine—and, of course, great customers. Please, mes amis, take your tables, sit down and be comfortable. Tonight's wine selection will arrive shortly, courtesy of my faithful waiter. François, kindly head down to the wine cellar and bring back the 2006 Quinta Do Infantado from Portugal. Henri brought in three cases today and left them by that collection of alien artifacts. Merci, François. Given today's topic, mes amis, we will be serving something a little different, a deep cherry-chocolaty, ruby-red port.

This time around, I've decided to let my faithful waiter select the menu. Unfortunately, as my mother used to say, his eyes are bigger than his stomach. Consequently, we needed to enlist the help of a really cool program to run his selection of really cool programs. As François will attest, putting together a menu can be difficult when so many great packages exist—the small, relatively trouble-free desktop applications you can install and try from your package manager, whether it be Synaptic, YaST or your distribution's favored package manager. To check some of them out, fire up your package manager and take a look at what's available. It's like Christmas or your birthday every time you look—free software, and lots of it, at your fingertips.

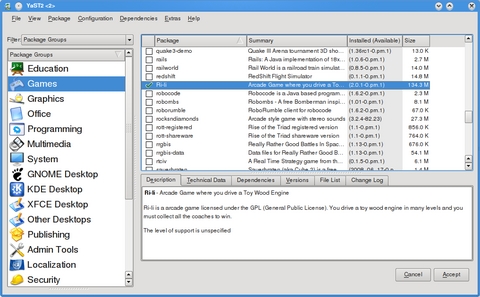

The computer I am using right now is running OpenSUSE, and frankly, it came with lots of cool software. But, as with all good things, I always want more, as would most people in this restaurant, I am sure. To try some cool new package, without knowing what it might be, start YaST and select Software Management from the menu. A second window opens from which you can search for a particular package. Let's say you want to install an instant-messaging client—other than the one your distribution came with, that is. Enter the word “instant” in the search field, and all of the packages that have instant in either their package name or description appear in the window to the right. You suddenly learn about Empathy or Pidgin and decide to give them a try.

Click on a package name, and a description of the software appears in the tabbed Description window in the right lower half of the screen (Figure 1). If this is the package you want, click on the check box next to the package name, then click the accept button in the bottom right-hand corner. Should there be dependencies associated with the package you chose to install, a pop-up window appears informing you of that fact. Click Continue, and the installation proceeds. That's all there is to it. If you'd rather browse, click the drop-down box labeled Filter, and select Package Groups to discover packages arranged according to, yes, groups. Looking through games, say you discover a cool-sounding program called Ri-Li, a wooden train arcade game, and decide to install it (Figure 1). By the way, Ri-Li actually is a great game, and I highly recommend it. Your kids will love it.

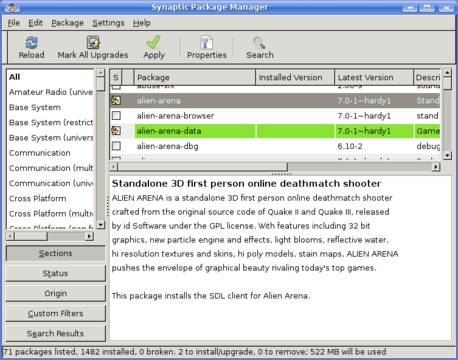

Installing software using the package manager from other distributions is just as easy, even if it does look a little different (see Synaptic's interface in Figure 2). This is all great fun and a great way to discover some of the amazingly cool software that free and open-source programmers have created. There's also little to worry about if you do your hunting and installing through your distribution's package manager. With multiple ways to search, descriptions of the packages and automatic installation of prerequisite packages, there's almost no reason not to load up, experiment and discover cool new stuff.

Figure 2. With installers like Synaptic, there's almost no reason not to try out at least one cool package every day.

However, if you are looking to try out packages that are more server-oriented, you might be a bit more reluctant. For situations where that cool software effectively comes down to installing a server and all its associated packages, things can become a bit more complex. For instance, installing a content management system isn't just a matter of downloading a package and having the prerequisites install automatically. You may not find the package in your distribution's repository at all. Once you know what you want to try, you'll still need a computer configured with an Apache server, PHP, MySQL (or PostgreSQL), a mail agent like Postfix, a handful of Perl modules and possibly a great deal more. That's why servers often are still the realm of career system administrators (and also why they get the big bucks).

Wouldn't it be awesome if you could just download a server running content management systems like Drupal or Joomla!, or customer relationship management software like SugarCRM or vTiger? Maybe what you really want to do is take an enterprise document management package like Alfresco for a spin or set up a bug-tracking system like Mantis or Bugzilla. And, what if you could have all those rather more complex prerequisites like the Web server, the mail agent and so on already taken care of? Well, you can. Several companies offer prebuilt servers running great open-source software packages like those I've mentioned. You just need to know where to look and how to run them.

Many of these systems are built as VMware images, though not exclusively. You'll find images to run on QEMU or KVM (both of which I've covered in earlier Cooking with Linux columns), Parallels, VMware and others. All of these packages perform hardware virtualization, literally reproducing a PC's hardware in memory so that you can install and run other Linux distributions (or BSD or Windows) on your PC. You create a virtual disk, boot from a CD or CD image, and install on that virtual hard drive. Then, you can run that new machine on your current desktop.

I am currently running OpenSUSE on this notebook, but I have several virtual machines installed as well. In a few seconds, I can start a virtual machine running Mandriva, Fedora, Puppy Linux, Kubuntu, CentOS and others. I do this regularly to test and run different Linux distributions. Those distributions each reside inside a disk image on my system. When the virtual machine is shut down, those distributions and their machines are just big files. That's the idea behind running enterprise software in a virtual appliance and where we start exploring.

Let's start our adventure at the aptly named Virtual Appliances (virtualappliances.net), a company that produces small Linux-based appliances that can be run from a virtual machine. These machines are prebuilt and configured with tools like Cacti, ntop or a LAMP (or LAPP) environment, and more. Just download, extract, and get ready for some quick machine deployments. For my example, I've decided to download the ntop appliance in VMware format. Because I don't have VMware on my notebook, I took advantage of VMware's free VMware Player, available from www.vmware.com/download/player. This is not the full VMware virtualization suite from which you can install and build your own machine. It is literally a player, as though that virtual appliance you are downloading were a movie you wanted to watch—not just any movie, but a really cool movie you can interact with.

First, download your machine from Virtual Appliances, and extract the tarred or zipped bundle somewhere on your hard disk. Next, download and install VMware Player from the site—you'll find versions for a number of architectures. When you start VMware Player (Figure 3), it offers some basic options that get right to the heart of the matter. You can open an existing virtual machine or download a virtual appliance. Click the Open button and navigate to where you have extracted the virtual appliance, then boot it.

Figure 3. The VMware Player lets you play a virtual appliance like you would play a movie—a movie you can interact with no less.

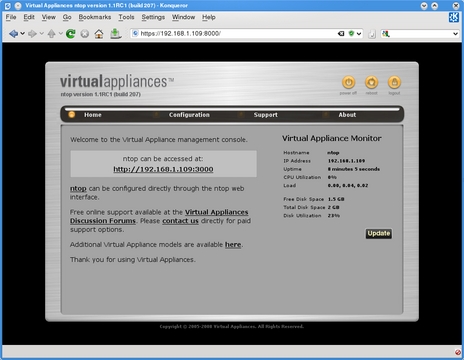

Once the machine is booted, a message tells you the address you can use to log on to the VA Management Console, in this case https://192.168.1.109:8000 (Figure 4). Make sure you read the final boot messages so you can get the right address. Open your favorite browser, surf to this address, and enter the console's user name and password (admin and admin). From here, you'll be able to configure the virtual machine further or get information on the various packages that are installed. For instance, the VA console tells me that ntop is running on http port 3000.

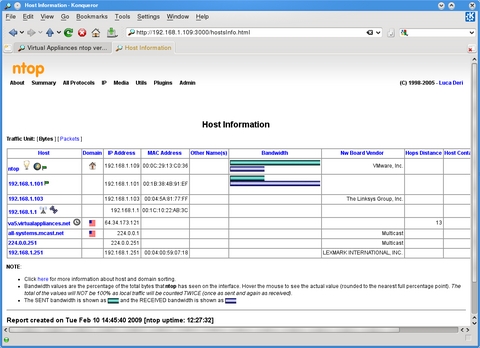

Using the information provided, I then can start using the installed software. ntop now sits on my system, listening to network traffic and gathering statistics (Figure 5). Everything about this feels like I am running a separate machine. It has its own IP address, runs independently of any other system on the network and is self-contained.

Figure 5. The virtual appliance, in this case using ntop, is up and rolling seconds after the boot completes.

Before I move on, remember that Download button on the front of the VMware Player? That button will open a browser to VMware's collection of virtual appliances, many of which are free, community-contributed builds. It's also a great place to look for other virtual appliances. There's a huge selection sorted into categories along with descriptions and user ratings.

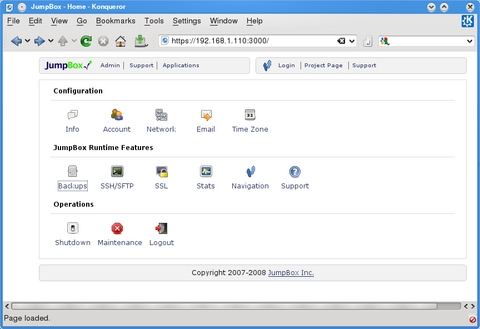

Another site you might want to visit is JumpBox (www.jumpbox.com). Once again, there are tons of virtual machines available, sorted into categories. JumpBox builds machines running the latest enterprise applications, but it does charge for this service (although at $149 annually, it seems inexpensive). JumpBox does, however, provide slightly older releases for free. Even if you don't want to shell out the dollars for a membership, you still can download and evaluate a number of great packages.

The VMware Player isn't the only game in town. Another great piece of virtualization software is VirtualBox, an open-source package freely distributed under the GPL. It's one I use every day, and one I highly recommend. Let's use VirtualBox to run an appliance from JumpBox. I've selected and downloaded a free copy of SugarCRM for this demonstration.

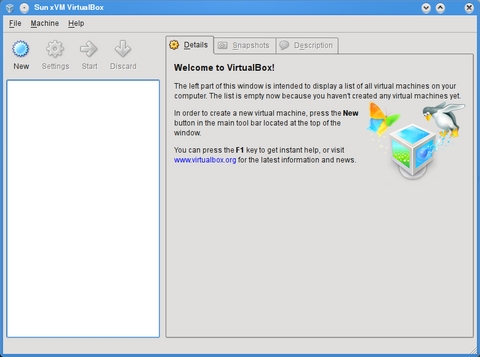

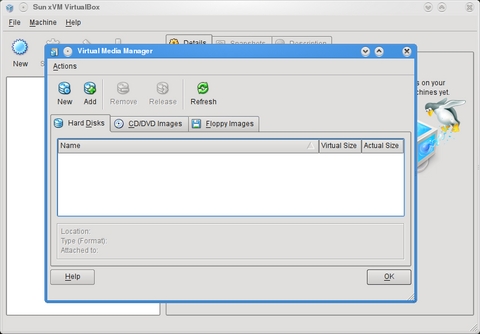

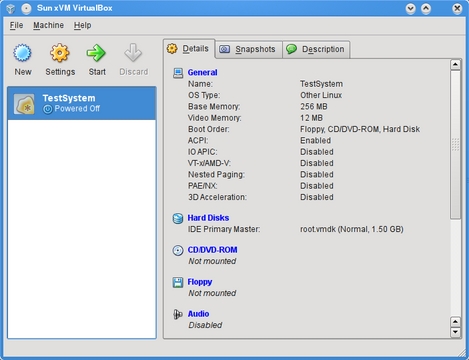

Visit virtualbox.org, download a copy of VirtualBox for your distribution, and install it. When you start VirtualBox the first time, there are no machines running in it. Think of it as a blank slate, or better yet, a new computer with a blank hard drive waiting for your favorite distribution (Figure 6).

Next, you need to tell VirtualBox about the virtual appliance image. To do this, click File on the menu bar and select Virtual Media Manager. When the window appears (Figure 7), you can start adding the virtual disk images from which you'll boot your machine. Click the Add button, then navigate to the SugarCRM virtual appliance folder. Look for the root folder and attach the root.vmdk file. Usually, that vmdk file is all you need, but with JumpBox, there's another step that I'll visit shortly. Click OK to continue.

Figure 7. You'll need to tell VirtualBox about your virtual appliance so the machine you create can boot it.

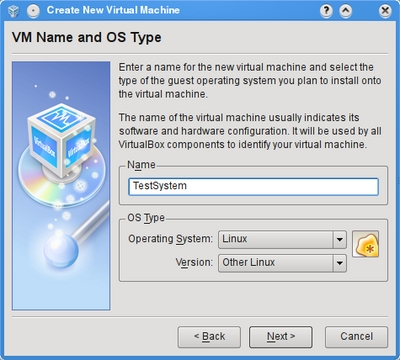

Unlike VMware Player, VirtualBox is the whole application, which means you can create different configurations of virtual machines, make a virtual hard drive and install a brand-new machine onto that disk. Click the New button on the top right, and you are presented with a wizard that takes you through all the steps necessary to create this machine. The first step is to name this machine and tell VirtualBox what OS it will be running (Figure 8). Click Next, and VirtualBox asks you how much memory (RAM) you want to give this machine. The default is 256MB. Click Next again, and you're asked about the hard disk you want to use.

This is where things get interesting. If you choose to use an existing disk, from an existing virtual machine, you can select it from the drop-down list. Machines you added from the Virtual Media Manager will appear here. On another day, you would click New and create a hard drive onto which to load the latest Ubuntu, Mandriva or whatever your favorite distribution might be. Assuming you went the virtual appliance route, select the image name, then click Next and you're almost done. Your new virtual machine is listed in the left sidebar (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Once a new machine has been created in VirtualBox, it shows up in a list on the left sidebar. There can be many machines here.

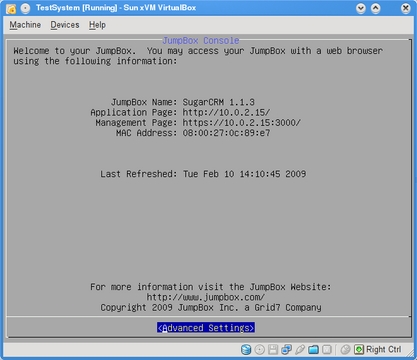

One last thing, and this is where it's actually easier with VMware's Player (which isn't GPL'd software, unfortunately). You'll see only one hard disk attached on the left. JumpBox appliances generally use two virtual disks for each machine: one for the root (root.vmdk) and one for data (data.vmdk). You need to add the data disk as well. Click the blue Hard Disks link, then navigate to the data disk and add it. The only thing you really need to be careful about here is making sure the root disk is first in line, as VirtualBox will boot from the hard disk. You'll find yourself back at the VirtualBox start screen but with at least one virtual machine ready to start. Click the Start icon, and your virtual appliance boots. Once booted, the virtual machine displays some information about the machine. On first boot into a virtual appliance, that screen most likely will have three links (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Your SugarCRM JumpBox is up and running under VirtualBox. Follow the links provided on the boot page to access your new machine's application or management page.

One link will take you to a page where you can finish configuring your machine—usually a minor task as almost everything else is done for you in the virtual appliance. There also will be links to access the application's page and its administration console. The JumpBox administration page gives you access to basic machine operations, such as performing a shutdown or running a backup so you can recover the machine state should disaster strike (Figure 11).

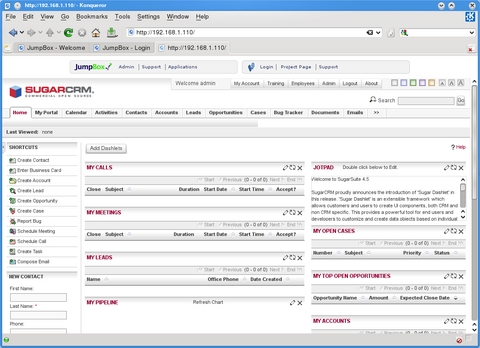

Of course, the real excitement comes from trying out that cool application or suite. By downloading a JumpBox virtual appliance and simply booting it (in either VMware Player or VirtualBox), I pretty much have instant access to a full SugarCRM implementation without all those steps involving Web servers, databases and so on (Figure 12).

Figure 12. What it's all about: a virtual appliance running enterprise-class software like SugarCRM in no time at all.

The new virtual machine runs like any other machine, and in some ways, it runs better. You can turn off a virtual machine and save its execution state so that when you reboot, at a later time, everything is exactly as it was. Any open application is open as it was. This kind of technology—the ability to load up virtual appliances and deploy them in minutes—is what cool really means. Take some time to check out Virtual Appliances, JumpBox and VMware's Virtual Appliance Marketplace, and I guarantee that it will change your sysadmin life forever.

As you can see, mes amis, it is possible to have it all, at least in a virtual sense. Best of all, you can have it fast (after the download completes). Unfortunately, we cannot save the restaurant's current state or that of the wine. All open bottles must be emptied; a delightful imposition, I am sure you will all agree. François, please attend to our guests and refill those glasses once more before we say Au revoir. Please, mes amis, raise your glasses and let us all drink to one another's health. A votre santé! Bon appétit!

Resources

JumpBox: jumpbox.com

Virtual Appliances: virtualappliances.net

VirtualBox XM: www.virtualbox.org

Download Free VMware Player: www.vmware.com/download/player/download.html

VMware's Virtual Appliance Marketplace: www.vmware.com/appliances

Marcel's Web Site: www.marcelgagne.com

Cooking with Linux: www.cookingwithlinux.com

WFTL Bytes!: wftlbytes.com

Marcel Gagné is an award-winning writer living in Waterloo, Ontario. He is the author of the Moving to Linux series of books from Addison-Wesley. Marcel is also a pilot, a past Top-40 disc jockey, writes science fiction and fantasy, and folds a mean Origami T-Rex. He can be reached via e-mail at marcel@marcelgagne.com. You can discover lots of other things (including great Wine links) from his Web sites at www.marcelgagne.com and www.cookingwithlinux.com.