OOo Off the Wall: What New Users Need to Know About OpenOffice.org

What do new users need to know about OpenOffice.org?

The question is worth asking. Any large piece of software has its own ways of doing things, and OpenOffice.org is no exception. In fact, because of its history and its design assumption that users are at least as interested in designing documents as in writing them, OpenOffice.org needs more orientation than most. OOo is not difficult to learn, but if you approach it expecting it to behave exactly like another office suite, especially MS Office, you are setting yourself up for frustration.

To orient themselves to OpenOffice.org, new users need to know its interface shortcomings and the limits of its on-line help. They also need to know the logic of its interface design and the importance of styles and templates in an efficient work flow. The more they know beforehand, the better the chance is that their first encounters with OpenOffice.org will go smoothly.

OpenOffice.org's long history has left it with three main interface standards:

The native one, as seen in the Border and Background tabs common to paragraphs in Writer, cells in Calc and objects in Draw.

The MS Office clone, such as the drawing toolbar in version 2.0.

Individual standards used by a single developer, such as the common design of Laurence Godard's wizards for installing new dictionaries and free fonts.

Any of these standards would be fine on their own. True, MS Office has more than its share of exhibits in the interface hall of shame, but copying it at least gives users a familiar environment. However, when mixed together, the result is an interface that is harder than it needs to be.

Moreover, to make matters worse, many parts of the interface fall into none of the three main levels. For example, in version 2.0, the warning that a Java Run Time environment is required is given in a pop-up window in Files > Document, but as part of the window's text in Tools > Mail Merge Wizard. Similarly, while styles are used in Writer to design page styles within the document, Impress and Draw use master slides, in which the design is set as an abstraction invisible in normal views of the file.

Because of these different interface standards, terminology in OpenOffice.org often is inconsistent. For example, "outline numbering" refers both to a type of list available in automatic numbering and numbering styles and to Tools > Outline Numbering, which sets up an altogether different type of outline numbering. Even more importantly, the latter manages which styles are used by several other tools.

Equally troublesome is the term "conditions". In the broadest sense, a condition simply is a set of circumstances under which a setting comes into effect. Yet, in practice, the word is applied to several different circumstances. In some cases, conditions are logical expressions that are set when a field or section is hidden; essentially, they're means to toggle a feature on or off. However, a conditional text field is one that specifically toggles two alternatives texts on and off. You would think that its name would be similar to the field that allows several alternative texts to be chosen. But, no, that is an input list, and it doesn't use conditionals at all. Then, in paragraph styles, "condition" is used to describe how the style's formatting changes in different contexts. All of these uses are related, but they are different enough that using the same term for all of them creates unnecessary difficulties.

Other confusing terminology includes:

Slides: the pages of a document in Draw. This usage probably reflects the close relation between Draw and Impress, but it is confusing when laying out brochures and other documents that also could be done in a word processor.

Numbering Styles: styles not only for numbered lists but also for bullet lists and quick outline numbering. Happily, this usage has been retired in version 2.0 in favor of the more accurate List Styles

Text Frames: a frame that is added without content for adding text and objects, as opposed to one added automatically when an object is added. Although the term is used in the Navigator, it is confusing because no menu item of that name is available. Instead, you choose Insert > Frame, which could refer to the object that encloses any object.

Faced with such interface consistencies, users may turn, naturally enough, to the OOo on-line help. However, while improving all the time, it has troubles of its own. Common complaints about the help include:

It doesn't always explain when features are unique to a particular operating system. For instance, because Windows supports the OLE standard while other operating systems do not, the Help contains references to using DDE Links that are unavailable under GNU/Linux.

It mentions features that are unavailable.

It does not mention features that are available.

Its explanations are incomplete, misleading or plain wrong.

It asssumes a level of knowledge about a subject that most users don't have.

Figure 1. OpenOffice.org's help is improving, but it still has a ways to go. Use it as your first resort, but not your last.

These problems don't occur happen regularly, but they do occur often enough to be a concern.

To be fair to the writers, the on-line help is getting better with each release. In fact, version 2.0's help is looking to be the best yet. Still, the on-line help consists of 90,000 words; it's the size of a small novel. And, despite the strong efforts of the project's Documentation team, much remains to be done.

Fortunately, unlike the shortcomings of proprietary software, those in OpenOffice.org can be combatted. If any of those in OpenOffice.org really disturb you, join the project and file an issue here and then vote for the issue being resolved. You even can campaign for changes if you feel strongly enough.

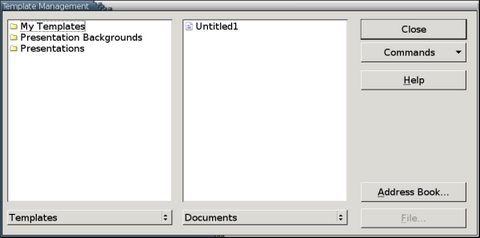

Several tools in OpenOffice.org create a virtual directory in their file managers. In other words, the view you have in the tool does not correspond to any actual system of folders on your hard drive. You can move around the virtual directory from within the tool, but you cannot move outside it. Tools that have virtual directories include File > Templates > Organize and Tools > Gallery.

Figure 2. Virtual directories--directories that correspond to nothing on the hard drive--are used by OpenOffice.org to simplify the display. However, they can be confusing if you want to find where the files actually are located.

The main reason for virtual directories is to give a unified view of the templates available from both the main installation and your own customized user account. Instead of forcing you to navigate through a series of directories that are useless for your purpose, OpenOffice.org creates an artificial view.

Think of a virtual directory as something similar to the placement of My Documents at the top of the folder hierarchy in the Windows Explorer. Both are artificial views created for convenience.

In most cases, you should not need to look at the hard drive directories that make up the virtual directories. However, in case you ever need to, you can find them by looking at Tools > Options > OpenOffice.org > Paths.

Styles, graphics, tables and other objects always have names in OpenOffice.org. These names help you to manage your documents. They also extend the functionality of the Navigator, which works better when objects are given meaningful names.

Names are assigned when an element is created or added to the document. Default names consist of the element and the first available number, for example, Graphic1 for the first unnamed graphic in a Writer document.

In a simple document that won't be revised, the default names are usually good enough. But in a longer document with a long shelf life, they can slow you down. For example, what is the name of the file used by Graphic1? You can open the Graphics tab to find out, but you won't be able to tell from the Navigator. By using descriptive names, you can save yourself the trouble of drilling down to find the source file.

The best naming convention depends on your work habits and the elements, but some useful ones are:

By functionality: for example, Chapter Title for a style for chapter titles

By format: for example, Graphic - No Border for a frame

By file: for example, portrait.png for a graphic. How useful this convention is depends partly on how descriptive the file names are.

By caption: for example, Unemployment Figures, 1999-2001. If the caption is numbered, you might want to include that but not alone. Otherwise, you are back to the problem of undescriptive names.

There is no correct naming convention for everybody, simply one that suits your thinking and work habits.

Whatever conventions you choose, decide them at the start and stick to them. You can rename objects by selecting them and opening the right-click window, but the easiest time to name an element is when you make or add it.

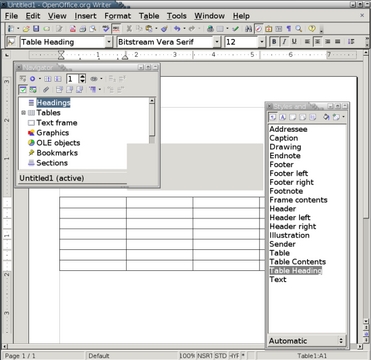

Like Adobe's proprietary products, OpenOffice.org always has made heavy use of floating windows. Floating windows are small windows that sit on top the main editing window. They can be moved to whatever position is convenient or docked to one side of the editing window.

Figure 3. Floating windows, toolbars and tear-off menus are fundamental to OpenOffice.org's internal logic.

OpenOffice.org uses four main floating windows:

The Navigator (F5): a tool for moving around in a document, outlining and managing master documents. It is most powerful when you name objects in a meaningful way.

Styles and Formatting (formerly the Stylist) (F11): a tool for applying and managing styles.

The Data Source Window(F4): a tool for managing registered databases and adding the information in them to documents.

The Gallery (Tools > Gallery): OpenOffice.org's built-in expandable clipart collection

In addition, applications may have other floating windows, such as the Task and Slide Sorter panes in Impress.

With version 2.0, the concept of floating windows has been augmented by floating toolbars. These toolbars open automatically, depending on the cursor position. They replace the sliding menus and the menus opened by a long-click in earlier versions. The only problem with them is they open in the center of the editing window, which usually is precisely where you are working, and have to be moved to one side.

OpenOffice.org has two ways of designing a document, manual overrides and styles. Manual overrides are by far the most common way of designing a document. Using manual overrides, whenever you want to change the default formatting, you select a portion of the document--for example, a page or a group of characters--and then apply the formatting using the toolbars or one of the menus. Usually, it's Insert or Format, although Tools has a role or two to play. Every time you want to format something, you do it individually. This style of formatting is popular only because it requires no special knowledge. In effect, it involves using a word processor as though it were a typewriter.

The alternative is to use styles. Styles are a list of format settings. Their advantage is you set them up in one place and then tag the parts of your document where you want to use them. If you want to change the format of all the tagged areas, you don't have to visit each area individually, the way you do when using manual overrides. Instead, you change the style settings. Instantly, all the areas tagged with that style also are changed.

For example, imagine that you are preparing a 10-page essay for a class. You have decided to use Bitstream Vera Sans with a size of 10 points. An hour before class, you re-read the professor's instructions and find that she only accepts work written with a serif font of 12 points. If you used overrides, you would barely have time to change the font in every paragraph. By contrast, if you used styles, you could change the font to 12 point Bitstream Vera Serif and be ready to re-print your essay in less than a minute. By using styles, you save yourself untold time and effort. You also force yourself to get organized, never a bad thing.

Styles are created by right-clicking on the Styles and Formatting (or Stylist) floating window and selecting New from the pop-up menu.

The advantages of styles are compelling in any office suite. Yet, in OpenOffice.org, they are even more compelling than usual. OpenOffice.org greatly extends the concept of styles. Writer not only has the paragraph and character styles of the average word processor, but it also has styles for pages, lists and frames. What's more, OpenOffice.org makes the concept of styles prominent in other applications, too. Styles in Draw, for example, are a considerable time saver in a graphics project.

This proliferation of styles gives OpenOffice.org more power than rival office suites. However, it also means that if you don't use styles, you won't be able to use many advanced features. They're simply unavailable for use with manual overrides.

Designing a document every time you sat down to write would be overwhelming. Nor would you want everyone working on a project to design his or her own template. In either case, time would be wasted and efforts duplicated. Yet that is what you do every time you start a document using File > New.

Sometimes, of course, you have no choice except to start a new document. However, at the cost of a little planning, you can save enormous time and effort by designing a few templates to meet most of your needs.

Templates are a special category of OpenOffice.org documents that can be used to structure other documents. Templates are not unique to OpenOffice.org. However, because of the program's emphasis on styles, they play a larger role in OOo than in most other office applications. All OpenOffice.org applications except Math use them. Contents also can be stored in them, which is especially important for Impress's Wizard, which lets you choose the structure of a presentation before you start to create it. But the main purpose of templates is to store structure for re-use.

OpenOffice.org comes with a few templates and more can be downloaded. More importantly, you can design your own templates. Designing your own templates begins with thinking about the types of documents that you write. For instance, if you are a student, you might find that you write three main types of documents: essays for classes, informal letters home and formal letters to apply for summer jobs. Therefore, you would want a template for each of these types of documents. Probably, too, you would want to design a generic template for other documents. You could set the generic template as the default, and choose the others as you needed them. Once you create these four templates, save them using File > Templates > Save.

After this initial work, most of your documents already are designed before you have to write them. The only change to your work flow is that instead of starting a document by selecting File > New and a document type, you select File > New > Documents and Templates.

The first time a new user encounters OpenOffice.org, other impressions probably will be lost in the overwhelming sense of difference. If you are used to working another way, you also may jump to the conclusion that OpenOffice.org's way of doing things is inferior.

If you are interested in learning OpenOffice.org, get to know these quirks. Then work with them for a couple of weeks before deciding what you think of them. Only then will you have a chance of getting beyond your initial impression.

It may be that OpenOffice.org's ways aren't yours. If so, you have no shortage of materials. If you prefer to work from the command line, LaTeX may be a better tool for you. If you've always formatted manually and don't want to change, then a less styles-oriented office application, such as Abiword or KOffice, might be a better choice. However, if you know what to expect going in, you can work with OpenOffice.org's quirks instead of being puzzled by them--and make an informed decision rather than one based on the comfort of familiarity.

Thanks to Alexandro Colorado for suggesting that this topic needed to be covered.

Bruce Byfield is a course designer and instructor and a computer journalist who writes regularly for NewsForge and the Linux Journal Web site.