Web 2.0 Development with the Google Web Toolkit

There's much hype related to Web 2.0, and most people agree that software like Google Maps, Gmail and Flickr fall into that category. Wouldn't you like to develop similar programs allowing users to drag around maps or refresh their e-mail inboxes, all without ever needing to reload the screen?

Until recently, creating such highly interactive programs was, to say the least, difficult. Few development tools, little debugging help and browser incompatibilities all added up to a complex mix. Now, however, if you want to produce such cutting-edge applications, you can use modern software methodologies and tools, work with the high-level Java language, and forget about HTML, JavaScript and whether Firefox and Internet Explorer behave the same way. The Google Web Toolkit (GWT) makes it easy to do a better job and produce more modern Web 2.0 programs for your users.

This question has several answers, including Sir Tim Berners-Lee's (the creator of the World Wide Web) view that it's just a reuse of components that were there already. It originally was coined by Tim O'Reilly, promoting “the Web as a platform”, with data as a driving force and technologies fostering innovation by assembling systems and sites that get information and features from distributed, different, independent developers and services.

This notion goes along with the idea of letting users run applications entirely through a browser, without installing anything on their machines. These new programs usually feature rich, user-friendly interfaces, akin to the ones you would get from an installed program, and they generally are achieved with AJAX (see the What Is AJAX? sidebar) to reduce download times and speed up display time.

Web 2.0 applications use the same infrastructure that developers are largely already familiar with: dynamic HTML, CSS and JavaScript. In addition, they often use XML or JSON for representing and communicating data between the server and browser. This data communication is often done using Web service requests via the DOM API XMLHttpRequest.

What Is AJAX?

The standard model for Web applications is something like this: you get a screenful of text and fields from a server, you fill in some fields, and when you click a button, the browser sends the data you typed to a server (wait), which processes it (wait), and sends back an answer (wait), which your browser displays, and then the cycle restarts. This is by far the most common way Web applications operate, and you must get used to the delays. Nothing happens immediately, because every answer that needs data from a server requires a round trip.

AJAX (Asynchronous JavaScript And XML) is a technique that lets a Web application communicate in the background (asynchronously) with a Web server to exchange (send or receive) data with it. This does away with the requirement to reload the whole page after every action or user click. Thus, using AJAX increases the level of interaction, does away with waiting for pages to reload and allows for enhanced functionality. A well-programmed application will send requests in the background, as you are doing other things, so you won't have to stare at a blank screen or a turning-hourglass cursor. This is the Asynchronous part of AJAX acronym.

The next part of the AJAX acronym is JavaScript. JavaScript allows a Web page to contain a program, and this program is what allows the Web page to connect to a server as previously described. However, it's not just a question of having JavaScript, but also of how it is implemented in the browser. Both Firefox and Internet Explorer both provide AJAX access, but with some differences, so programmers must take those differences into account when doing the connection. Data is usually retrieved using XMLHttpRequest, but other techniques are possible, such as using iframes.

Finally, the last part of the AJAX acronym is XML. XML is a standard markup language, used for sharing and passing information. As we've seen, the name of the DOM API for making Web service requests is named XMLHttpRequest, and most likely, the original intent was that XML be used as the protocol for exchanging data between browser and server. However, neither the X in AJAX nor the XML in XMLHttpRequest means that you have to use XML; any data protocol at all, including no protocol, can be used.

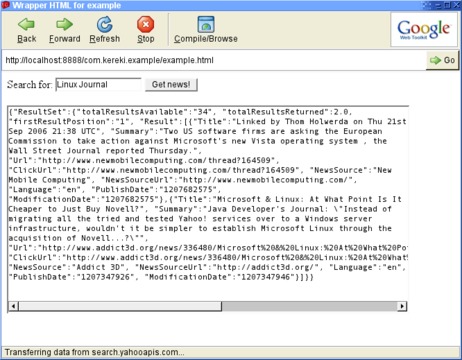

JSON (JavaScript Object Notation) often is used; it's more lightweight than XML, and as you might guess by its name, is often a better fit for JavaScript. See Figure 3 for some actual JSON code; remember, it's not meant to be clear to humans, but compact and easy to understand for machines.

AJAX comprises basic technologies that have been around for a while now, and the AJAX term itself was created in 2005 by Jesse Garrett. GWT uses AJAX to allow the client program to communicate with the server or execute procedures on it in a fully transparent way. Of course, you also can use AJAX explicitly for any special purposes you might have.

The Google Web Toolkit (GWT—rhymes with “nitwit”) is a tool for Web programmers. Its first public appearance was in May 2006 at the JavaOne conference. Currently (at the time of this writing), version 1.5.3 has just been released. It is licensed mainly under the Apache 2.0 Open Source License, but some of its components are under different licenses. Don't confuse JavaScript with Java; despite the name, the languages are unrelated, and the similarities come from some common roots.

In short, GWT makes it easier to write high-performing, interactive, AJAX applications. Instead of using the JavaScript language (which is powerful, but lacking in areas like modularity and testing features, making the development of large-scale systems more difficult), you code using the Java language, which GWT compiles into optimized, tight JavaScript code. Moreover, plenty of software tools exist to help you write Java code, which you now will be able to use for testing, refactoring, documenting and reusing—all these things have become a reality for Web applications.

You also can forget about HTML and DHTML (Dynamic HTML, which implies changing the actual source code of the page you are seeing on the fly) and some additional subtle compatibility issues therein. You code using Java widgets (such as text fields, check boxes and more), and GWT takes care of converting them into basic HTML fields and controls. Don't worry about localization matters either; with GWT, it's easy to produce locale-specific versions of code.

There's another welcome bonus too. GWT takes care of the differences between browsers, so you don't have to spend time writing the same code in different ways to please the particular quirks of each browser. Typically, if you just code away and don't pay attention to those small details, your site will end up looking fine in, say, Mozilla Firefox, but won't work at all in Internet Explorer or Safari. This is a well-known classic Web development problem, and it's wise to plan for compatibility tests before releasing any site. GWT lets you forget about those problems and focus on the task instead.

According to its developers, GWT produces high-quality code that matches (and probably surpasses) the quality (size and speed) of handwritten JavaScript. The GWT Web page contains the motto “Faster AJAX than you can write by hand!”

GWT also endeavors to minimize the resulting code size to speed up transfers and shorten waiting time. By default, the end code is mostly unreadable (being geared toward the browser, not a snooping user), but if you have any problems, you can ask for more legible code so you can understand the relationship between your Java code and the produced JavaScript.

Before installing GWT, you should have a few things already installed on your machine:

Java Development Kit (JDK), so you can compile and test Java applications; several more tools also are included.

Java Runtime Environment (JRE), including the Java Virtual Machine (JVM) and all the class libraries required for production and development environments.

A development environment—Google's own developers use Eclipse, so you might want to follow suit. Or, you can install GWT4NB and do some tweaking and fudging and work with NetBeans, another popular development environment.

GWT itself weighs in at about 27MB; after downloading it, extract it anywhere you like with tar jxf ../gwt-linux-1.5.3.tar.bz2. No further installation steps are required. You can use GWT from any directory.

For this article, I used Eclipse. For more serious work, you probably also will require some other additions, such as the Data Tools Platform (DTP), Eclipse Java Development Tools (JDT), Eclipse Modeling Framework (EMF) and Graphical Editing Framework (GEF), but you easily can add those (and more) with Eclipse's own software update tool (you can find it on Eclipse's main menu, under Help—and no, I don't know why it is located there).

Before starting a project, you should understand the four components of GWT:

When you are developing an application, GWT runs in hosted mode and provides a Web browser (and an embedded Tomcat Web server), which allows you to test your Java application the same way your end users would see it. Note that you will be able to use the interactive debugging facilities of your development suite, so you can forget about placing alert() commands in JavaScript code.

To help you build an interface, there is a Web interface library, which lets you create and use Web browser widgets, such as labels, text boxes, radio buttons and so on. You will do your Java programming using those widgets, and the compilation process will transform them into HTML-equivalent ones.

Because what runs in the client's browser is JavaScript, there needs to be a Java emulation library, which provides JavaScript-equivalent implementations of the most common Java standard classes. Note that not all of Java is available, and there are restrictions as to which classes you can use. It's possible that you will have to roll your own code if you want to use an unavailable class. As of version 1.5, GWT covers much of the JRE. In addition, as of version 1.5, GWT supports using Java 5.

Finally, in order to deploy your application, there is a Java-to-JavaScript compiler (translator), which you will use to produce the final Web code. You will need to place the resulting code, the JavaScript, HTML and CSS on your Web server later, of course.

If you are like most programmers, you probably will be wondering about your converted application's performance. However, GWT generates ultra-compact code that can be compressed and cached further, so end users will download a few dozen kilobytes of end code, only once. Furthermore, with version 1.5, the quality of the generated code is approaching (and even surpassing) the quality of handwritten JavaScript, especially for larger projects. Finally, because you won't need to waste time doing debugging for every existing Web browser, you will have more time for application development itself, which lets you produce more features and better applications.

Packages

Using GWT requires learning about several packages. The most important ones are:

com.google.gwt.http.client: provides the client-side classes for making HTTP requests and processing the received responses. You will use it if you need to do some AJAX on your own, beyond the calls done by GWT itself.

com.google.gwt.i18n.client: provides internationalization support. You will need it if you are developing a system that will be available in several languages.

com.google.gwt.json.client and com.google.gwt.xml.client: used for parsing and reading XML and JSON data.

com.google.gwt.junit.client: used for building automated JUnit tests.

com.google.gwt.user.client.ui: provides panels, buttons, text boxes and all the other user-interface elements and classes. You certainly will use these.

com.google.gwt.user.client.rpc and com.google.gwt.user.server.rpc: these have to do with remote procedure calls (RPCs). GWT allows you to call server code transparently, as if the client were residing in the same machine as the server.

You can find information on these and other packages on-line, at google-web-toolkit.googlecode.com/svn/javadoc/1.5/index.html.

Now, let's turn to a practical example. Creating a new project is done with the command line rather than from inside Eclipse. Create a directory for your project, and cd to it. Then create a project in it, with:

/path/to/GWT/projectCreator -eclipse ProjectName

Next, create a basic empty application, with:

/path/to/GWT/applicationCreator -eclipse ProjectName \

com.CompanyName.client.ApplicationName

Then, open Eclipse, go to File→Import→General, choose Existing Projects into Workspace, and select the directory in which you created your project. Do not check the Copy Projects into Workspace box so that the project will be left at the directory you created.

After doing this, you will be able to edit both the HTML and Java code, add new classes and test your program in hosted mode, as described earlier. When you are satisfied with the final product, you can compile it (an appropriate script was generated when you created the original project) and deploy it to your Web server.

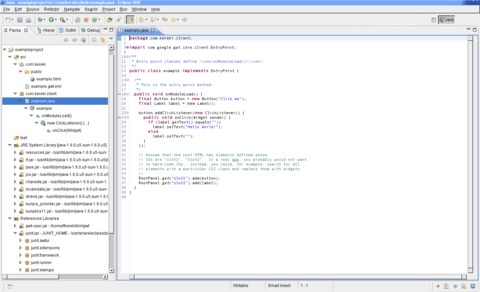

Let's do an example mashup. We're going to have a text field, the user will type something there, and we will query a server (okay, with only one server, it's not much of a mashup, but the concept can be extended easily) and show the returned data. Of course, for a real-world application, we wouldn't display the raw data, but rather do further processing on it. The example project itself will be called exampleproject, and its entry point will be example, see Listing 1 and Figure 1.

Listing 1. Projects must be created by hand, outside Eclipse, and imported into it later.

# cd

# md examplefiles

# cd examplefiles

# ~/bin/gwt/projectCreator -eclipse exampleproject

Created directory ~/examplefiles/src

Created directory ~/examplefiles/test

Created file ~/examplefiles/.project

Created file ~/examplefiles/.classpath

# ~/bin/gwt/applicationCreator -eclipse exampleproject \

com.kereki.client.example

Created directory ~/examplefiles/src/com/kereki

Created directory ~/examplefiles/src/com/kereki/client

Created directory ~/examplefiles/src/com/kereki/public

Created file ~/examplefiles/src/com/kereki/example.gwt.xml

Created file ~/examplefiles/src/com/kereki/public/example.html

Created file ~/examplefiles/src/com/kereki/client/example.java

Created file ~/examplefiles/example.launch

Created file ~/examplefiles/example-shell

Created file ~/examplefiles/example-compile

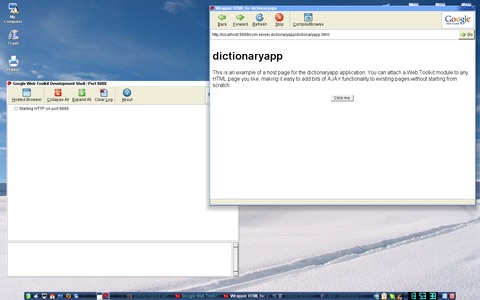

According to the Getting Started instructions on the Google Web Toolkit site, you should click the Run button to start running your project in hosted mode, but I find it more practical to run it in debugging mode. Go to Run→Debug, and launch your application. Two windows will appear: the development shell and the wrapper HTML window, a special version of the Mozilla browser. If you do any code changes, you won't have to close them and relaunch the application. Simply click Refresh, and you will be running the newer version of your code.

Now, let's get to our changes. Because we're using JSON and HTTP, we need to add a pair of lines:

<inherits name='com.google.gwt.json.JSON'/>

to the example.gwt.xml file. We'll rewrite the main code and add a couple packages to do calls to servers that provide JSON output (see The Same Origin Policy sidebar). For this, add two classes to the client: JSONRequest and JSONRequestHandler; their code is shown in Listings 2 and 3.

The Same Origin Policy

The Same Origin Policy (SOP) is a security restriction, which basically prevents a page loaded from a certain origin to access a page from a different origin. By origin, we mean the trio: protocol + host + port. In https://www.mysite.com:80/some/path/to/a/page, the protocol is http, the host is www.myhost.com, and the port is 80. The SOP would allow access to any document coming from https://www.mysite.com:80, but disallow going to https://www.mysite.com:80/something (different protocol), https://dev.mysite.com:80/something (different host) or https://www.mysite.com:81/something (different port).

Why is this a good idea? Without it, it would be possible for JavaScript from a certain origin to access data from another origin and manipulate it secretly. This would be the ultimate phishing. You could be looking at a legitimate, valid, true page, but it might be monitored by a third party. With SOP in place, you know for certain that whatever you are viewing was sent by the true origin. There can't be any code from other origins.

Of course, for GWT, this is a bit of a bother, because it means that a client application cannot simply connect to any other server or Web service to get data from it. There are (at least) two ways around this: a special, simpler way that allows getting JSON data only or a more complex solution that implies coding a server-side proxy. Your client calls the proxy, and the proxy calls the service. Both solutions are explained in the Google Web Toolkit Applications book (see Resources). In this article, we use the JSON method, and you can find the source code at www.gwtsite.com/code/webservices.

The simple JSON method requires a special callback routine, and this could be a showstopper. However, many sites implement this, including Amazon, Digg, Flickr, GeoNames, Google, Yahoo! and YouTube, and the method is catching on, so it's quite likely you will be able to find an appropriate service.

Listing 2. Source Code for the JSONRequest Class

package com.kereki.client;

public class JSONRequest {

public static void get(String url,

JSONRequestHandler handler) {

String callbackName = "JSONCallback"+handler.hashCode();

get(url+callbackName, callbackName, handler);

}

public static void get(String url, String callbackName,

JSONRequestHandler handler) {

createCallbackFunction(handler, callbackName);

addScript(url);

}

public static native void addScript(String url) /*-{

var scr = document.createElement("script");

scr.setAttribute("language", "JavaScript");

scr.setAttribute("src", url);

document.getElementsByTagName("body")[0].appendChild(scr);

}-*/;

private native static void createCallbackFunction(

JSONRequestHandler obj,

String callbackName) /*-{

tmpcallback = function(j) {

obj.@com.kereki.client.JSONRequestHandler::

onRequestComplete(

Lcom/google/gwt/core/client/JavaScriptObject;)(j);

};

eval( "window." + callbackName + "=tmpcallback" );

}-*/;

}

Note that the last two methods are written in JavaScript instead of Java; the JavaScript code is written inside Java comments. The special @id... syntax inside the JavaScript is used for accessing Java methods and fields from JavaScript. This syntax is translated to the correct JavaScript by GWT when the application is compiled. See the GWT documentation for more information.

Listing 3. Source Code for the JSONRequestHandler Class

package com.kereki.client;

import com.google.gwt.core.client.JavaScriptObject;

public interface JSONRequestHandler {

public void onRequestComplete(JavaScriptObject json);

}

You can find the code for this listing and the previous one at www.gwtsite.com/code/webservices.

Let's opt to create the screen completely with GWT code. The button will send a request to a server (in this case, Yahoo! News) that provides an API with JSON results. When the answer comes in, we will display the received code in a text area. The complete code is shown in Listing 4, and Figure 3 shows the running program.

Listing 4. Source Code for the Main Program

package com.kereki.client;

import com.google.gwt.core.client.EntryPoint;

import com.google.gwt.core.client.JavaScriptObject;

import com.google.gwt.user.client.ui.*;

import com.google.gwt.json.client.*;

import com.google.gwt.http.client.URL;

import com.kereki.client.JSONRequest;

import com.kereki.client.JSONRequestHandler;

public class example implements EntryPoint {

public void onModuleLoad() {

final TextBox tbSearchFor = new TextBox();

final TextArea taJsonResult = new TextArea();

taJsonResult.setCharacterWidth(80);

taJsonResult.setVisibleLines(20);

final HorizontalPanel hp1 = new HorizontalPanel();

Button bGetNews = new Button("Get news!",

new ClickListener() {

public void onClick(Widget sender) {

JSONRequest.get(

"https://search.yahooapis.com/"+

"NewsSearchService/V1/newsSearch?"+

"appid=YahooDemo&query="+

URL.encode(tbSearchFor.getText())+

"&results=2&language=en"+

"&output=json&callback=",

new JSONRequestHandler() {

public void onRequestComplete(

JavaScriptObject json) {

JSONObject jj= new JSONObject(json);

taJsonResult.setText(jj.toString());

};

}

);

}

});

hp1.add(new Label("Search for:"));

hp1.add(new HTML(" ",true));

hp1.add(tbSearchFor);

hp1.add(new HTML(" ",true));

hp1.add(bGetNews);

RootPanel.get().add(hp1);

RootPanel.get().add(new HTML("<br>",true));

RootPanel.get().add(taJsonResult);

}

}

The code in Listing 4 shows access to a single service, but it would be easy to connect to several sources at once and produce a mashup of news.

After testing the application, it's time to distribute it. Go to the directory where you created the project, run the compile script (in this case, example_script.sh), and copy the resulting files to your server's Web pages directory. In my case, with OpenSUSE, it's /srv/www/htdocs, but with other distributions, it could be /var/www/html (Listing 5). Users could use your application by navigating to https://127.0.0.1/com.kereki.example/example.html, but of course, you probably will select another path.

Listing 5. Compiling the Code and Deploying the Files to Your Server

# cd ~/examplefiles/ # sh ./example-compile Output will be written into ./www/com.kereki.example Copying all files found on public pathCompilation succeeded # sudo cp -R ./www/com.kereki.example /srv/www/htdocs/

We have written a Web page without ever writing any HTML or JavaScript code. Moreover, we did our coding in a high-level language, Java, using a modern development environment, Eclipse, full of aids and debugging tools. Finally, our program looks quite different from classic Web pages. It does no full-screen refreshes, and the user experience will be more akin to that of a desktop program.

GWT is a very powerful tool, allowing you to apply current software engineering techniques to an area that is lacking good, solid development tools. Being able to apply Java, a high-level modern language, to solve both client and server problems, and being able to forget about browser quirks and incompatibilities, should be enough to make you want to give GWT a spin.

Resources

Google Web Toolkit Applications by Ryan Dewsbury, Prentice-Hall, 2008.

Google Web Toolkit for AJAX by Bruce Perry, PDF edition, O'Reilly, 2006.

Google Web Toolkit Java AJAX Programming by Prabhakar Chaganti, Packt Publishing, 2007.

Google Web Toolkit Solutions: Cool & Useful Stuff by David Geary and Rob Gordon, PDF edition, Prentice Hall, 2007.

Google Web Toolkit Solutions: More Cool & Useful Stuff by David Geary and Rob Gordon, Prentice Hall, 2007.

Google Web Toolkit—Taking the Pain out of AJAX by Ed Burnett, PDF edition, The Pragmatic Bookshelf, 2007.

GWT in Action: Easy AJAX with the Google Web Toolkit by Robert Hanson and Adam Tacy, Manning, 2007.

AJAX: a New Approach to Web Applications: www.adaptivepath.com/ideas/essays/archives/000385.php

AJAX: Getting Started: developer.mozilla.org/en/docs/AJAX:Getting_Started

AJAX Tutorial: www.xul.fr/en-xml-ajax.html

Apache 2.0 Open Source License: code.google.com/webtoolkit/terms.html

Eclipse: www.eclipse.org

Google Web Toolkit: code.google.com/webtoolkit

GWT4NB, a Plugin for GWT Work with NetBeans: https://gwt4nb.dev.java.net

Java SE (Standard Edition): java.sun.com/javase

Java Development Kit (JDK): java.sun.com/javase/downloads/index.jsp

JSON: www.json.org

JSON: the Fat-Free Alternative to XML: www.json.org/xml.html

NetBeans: www.netbeans.org

Same Origin Policy, from Wikipedia: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Same_origin_policy

Web 2.0, from Wikipedia: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Web_2

What Is Web 2.0?, by Tim O'Reilly: www.oreillynet.com/pub/a/oreilly/tim/news/2005/09/30/what-is-web-20.html

XML: www.xml.org

Federico Kereki is a Uruguayan Systems Engineer, with more than 20 years' experience teaching at universities, doing development and consulting work, and writing articles and course material. He has been using Linux for many years now, having installed it at several different companies. He is particularly interested in the better security and performance of Linux boxes.