New Projects - Fresh from the Labs

To start off this month, I deal with my petrol-head side straightaway and look at the racing simulator VDrift. For those who read my column last month, you may recall I made a brief mention of this project. This month, I take a more in-depth look at it. To quote the Web site:

VDrift is a cross-platform, open-source driving simulation made with drift racing in mind. It's powered by the excellent Vamos physics engine. It is released under the GNU General Public License (GPL) v2. It is currently available for Linux, FreeBSD, Mac OS X and Windows (Cygwin).

This game is in the early stages of development but is already very playable. Currently the game features:

19 tracks: Barcelona, Brands Hatch, Detroit, Dijon, Hockenheim, Jarama, Kyalami, Laguna Seca, Le Mans, Monaco, Monza, Mosport, Nurburgring Nordschleife, Pau, Road Atlanta, Rudskogen, Spa Francorchamps, Weekend Drive and Zandvoort.

28 cars: 3S, AX2, C7, CO, CS, CT, F1, FE, FF, G4, GT, M3, M7, MC, MI, NS, RG, RS2, SB, T73, TC, TL, TL2, XG, XM, XS and Z06.

Compete against AI players.

Simple networked multiplayer mode.

Very realistic physics.

Mouse-/joystick-/keyboard-driven menus.

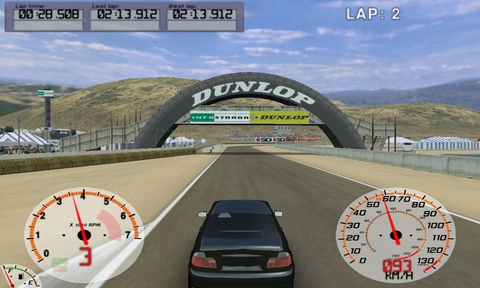

Determination is needed when approaching the notoriously dangerous and difficult corkscrew section at Laguna Seca.

Installation

I was pleasantly surprised by this project's main installation method, as it eschews all of the usual repository and source stuff and uses Autopackage instead. I've always been a big fan of Autopackage, because it combines the perks of a Windows-style package installation (double-click, Next, Next, Next, Finish—you get the idea) with the added structural benefits of a UNIX-style architecture. There is a source file buried deep under several layers of the Web page, but the choice given for Linux on the main page is an Autopackage, so we'll stick with that here and hopefully annoy some pedantic Debian developers in the process—the natural enemy of the Autopackage!

Grab the package and save it somewhere locally. Once it's downloaded, you need to flag it as executable (don't worry, this is just a once-off), either by turning the executable option on for the file in the file manager of your choice, or by entering the following at the command line:

$ chmod u+x VDrift-2007-03-23-full-2.package

Now, you can run the package simply by clicking on it, and follow the Next, Next, Next prompts. You can choose to install it locally or system-wide, depending on whether you have a root password. Note that you can run this from the command line, but it's a bit like mixing 12-year-old Scotch with Coke—it just defeats the purpose. If this is your first time with an Autopackage, before VDrift installs, Autopackage installs itself to your system along with a neat Add/Remove Programs-style utility called Manage third-party software in your system menu, where you can remove VDrift (or any other Autopackages) later if you want. Don't worry; this also is a one-time-only process. Autopackages will skip straight through to installing after you have Autopackage on your system.

During the installation, Autopackage checks your system for compatability, and if it encounters any problems, it tells you in the installation window. If you are missing any needed requirements, you can install them in the meantime and run the Autopackage again simply by clicking on it. In terms of libraries, the documentation says you need the following:

libsdl: simple direct media layer.

libglew: OpenGL extension utilities.

sdl-gfx: graphics drawing primitives library for SDL.

sdl-image: image file-loading library for SDL.

sdl-net: low-level network library for SDL.

vorbisfile: file-loading library for the Ogg Vorbis format.

libvorbis-dev: the Vorbis General Audio Compression codec.

Once the installation process is over, VDrift should install itself under your menu, somewhere along the lines of Games→Simulation→VDrift.

Usage

The first thing you should do is crank up the graphics as much as humanly possible. The default graphics level is very conservative, and even with the graphics turned up, it still has the occasional feel of “ye olde Pentium 133”. So, head to the Options→Display section, and then go to the Advanced section below. Texture size, Anisotropic filtering, Antialiasing and Lighting quality will all have a big effect on the look of the game. Back in the main Display section, you can switch between full-screen and windowed mode, as well as change the resolution. If you want to make life easier, you can choose between either miles or kilometers per hour, and enabling the track map really helps when driving somewhere unfamiliar.

VDrift Controls

W: gear up.

S: gear down.

Up arrow: accelerate.

Down arrow: brake.

Left/right arrows: steering.

Spacebar: handbrake.

F1–F6: camera angles.

Given the general emphasis on physics, you really do get the feeling that this game is meant to be controlled by a steering wheel. If you have one, please, plug it in. In the Controls section, you can tweak any wheel, pedals, joystick or joypad options under Joystick Options as well as adjust the force feedback settings. If you're a poor bloke like myself, and you can't afford a steering wheel and are stuck with a keyboard, you'll want to turn on the driving aids, such as traction control, ABS and the auto-clutch. I also found that to have any feel without constantly spinning off, I had to change Speed Affect on Steering to 100%.

Enough of this boring setup rubbish though, let's drive! Head into Practice Game, and select a car and a track. Remember, the physics engine is very harsh on driving and will show no quarter to any need-for-speed arcade-racer types. Do not glue the accelerator down! Just keep dabbing at it to begin with—particularly if you're using a keyboard—until you gain more confidence. I found the MC (Mini Cooper) and the XG (which appears to be some kind of BMW, perhaps a 5 series) to be the easiest cars to drive, and the easiest track is Weekend Drive, which had easy corners and will give you an initial feeling for the game.

The default view is behind the wheel, and at a fairly low graphics level, it will not give much of a speed sensation. Things just don't look that fast even in real life unless you have a lot of objects whizzing by your side, and VDrift is fairly minimal in terms of road-side distractions. I recommend keeping a close eye on the speed to begin with instead of just feeling it, so you can compare it to real life. In real life, would you take that corner at 73mph? No, you'll understeer into the railing or your back end will swing out. So, practice for half an hour on something long and twisty, such as the Nordschleife Nurburgring circuit, which is simply epic and one of the longest circuits in the world. This track is incredibly hard, and you'll keep coming off, but the corners are endless, and you'll learn to adapt very quickly to the harsher aspects of this game. Mind you, I am a bit of a masochist, so if it puts you off, try another track!

The early development bugs do show through almost immediately in VDrift. I found that restarting a track would cut the sound out, and when I tried to change graphical options, things kept resetting and would rarely stay the same between game sessions. When I was driving, I often ran into the kind of jumping physics that have always plagued large 3-D games, especially when you stray from the track. Several times after coming off a tricky hairpin, I had to restart the track. Racing is still pretty rudimentary, and it's not always obvious what you're doing, so things are still best in one-player mode. But, look past this, because you can see that so much passion and research went into this project, with its amazing touches and brilliant locations.

Yes, this game does have a lot of bugs, but it's allowed to—it's in development. You may curse and swear at this incomplete game, which is often ugly and quite harsh to play (and definitely not friendly to beginners). But, ten seconds later, a moment will come when everything looks beautiful, you're in the zone, control is coming naturally and an authentic touch by a big fan will put a huge grin on your face. There really is a large sense of ambition with this game, and if you can look past the early development flaws, you'll find a real gem. The code currently is being rewritten as a side project called Refactor, so I really hope this game sees the support and development it deserves, because it could be brilliant—definitely one to watch.

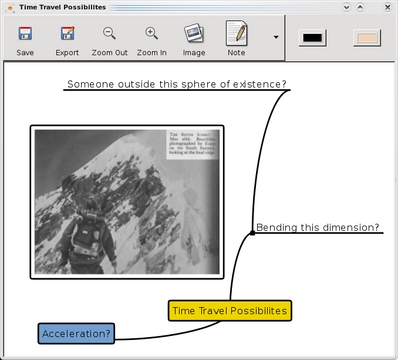

CharTr is an artistic piece of software made for fun to give mind mappers good usability. For those unfamiliar with mind mapping, Wikipedia says the following:

A mind map is a diagram used to represent words, ideas, tasks or other items linked to and arranged radially around a central key word or idea. It is used to generate, visualize, structure and classify ideas, and as an aid in study, organization, problem solving, decision making and writing.

Currently, its stated features are as follows:

Basic mind map with curved links.

Link folding.

Colors.

Outline box of several selected nodes.

Audio/text/images embedded as notes.

Automatic saving.

SVG, PNG, PDF and PS export.

Numerous keyboard shortcuts (with an eased keyboard navigation, vim-like).

Idea bookmarking.

Search for text in nodes.

Math equations.

Installation

CharTr does have a few obscure requirements, so you should look through your repositories. You need Python, PyGTK, Cairo, GStreamer, Numpy and python-plastex for mathematical equations. Once you have these sorted out, head to the Web site where you have a choice of a source tarball or Debian package.

If you grab the .deb package, install it by entering the following in a terminal from whichever directory contains the file:

$ sudo dpkg -i chartr_0.16_i386.deb

Now, run CharTr by entering:

$ chartr

If you get the source version, download and extract the tarball, and then open a terminal in the new CharTr directory.

You need to invoke Python manually, by entering the following:

$ python chartr.py

Usage

Once inside, click that big shiny New button, and a new window appears, called a Map. In the big expanse of white, left-clicking brings up a text cursor allowing you to type in some text. Press Enter, and the text is placed inside a box. The first of these is yellow, allowing for a central idea from which others ideas can flow. If you click on the original box and add some text somewhere else on the map, it is placed in a blue box, and a black line links to it. Right-clicking lets you move the map around, and if you look at the toolbar at the top, you can zoom in and out, as well as add images. If you check the drop-down box toward the right, you also can add bits of audio, notes or some already-provided icons—very handy! Once you've finished making a mind map, you can export it to a picture file. Check the documentation page at code.google.com/p/chartr/wiki/CharTrDocumentationEn for more information on general usage.

All in all, this is a nice and simple application with some great aesthetics that will find favor with students and teachers alike. It's still buggy for the moment, but I hope to see it included in major distros, especially educational ones.

Brewing something fresh, innovative or mind-bending? Send e-mail to John Knight at knight.john.a@gmail.com.

John Knight is a 24-year-old, drumming- and climbing-obsessed maniac from the world's most isolated city—Perth, Western Australia. He can usually be found either buried in an Audacity screen or thrashing a kick-drum beyond recognition.