Need a Script?

Of all the things a body can write, a great number of them these days require something a little different from the good-old word processor. Podcasts, corporate video presentations, radio and television advertisements, short and feature films, stage plays, animations, training videos and television shows all require scripts. More than that, they require scripts written to particular formatting standards.

Those formatting standards are stringent—an improperly formatted script won't be looked at twice by people who are used to working with proper scripts. When one is writing a book or an article, most of the work can be done in a simple text editor—almost everything that comes with a modern word processor is related to typesetting, which can be done as a whole separate step if one so desires. With scripts, the story is somewhat different. When you write for a script-based medium, the physical format of the script dictates a series of storytelling conventions that are enforced by the typesetting structure. Attempting to write a script without effective typesetting is a pain—the formatting gets in the way of the creative process.

In the bad-old days, there basically were two options (other than writing it out by hand and having a minion type it for you):

You could format on the fly as you go using tabs, carriage returns and spaces.

You could create a template for OpenOffice.org or a comparable word processor.

The former, as I alluded to already, is a major pain. The latter has the problem of not giving you the full range of flexibility sometimes needed in scripts, such as subscript or superscript annotation or simultaneous dialogue.

Writing a proper script requires a specialized tool, and specialized tools are expensive. In recent years, a number of commercial tools have grown up to address this need. However, the resulting commercial tools, such as Final Draft, are expensive and many have a reputation for being difficult to use and (in some cases) unreliable. None of these tools run on Linux without a bottle full of Wine and a couple good shots of whiskey, and even then your mileage may vary.

Last summer, however, a new tool emerged from a tortuous two-year beta period and attained usability—CeltX.

CeltX is the brainchild of a Newfoundland-based company that formed in 2005 and aimed to create the ultimate open-source screenwriting and preproduction program. After some early failed experiments with proprietary file formats, the project settled on an open system based on Mozilla and using XML, HTML and open-standards graphics formats to do its work.

Far more sophisticated than a mere document template, CeltX has all the tools a writer needs to develop a script from a single line concept through to a salable final draft. Beginning with a “text editor” that works more like a stripped-down version of OpenOffice.org Writer than it does like gedit, writers can input their notes organized in whatever way they find most useful—for example, creating a separate text file for every subplot or for every character's individual arc, in order to concentrate on the different threads of the story before marrying them together.

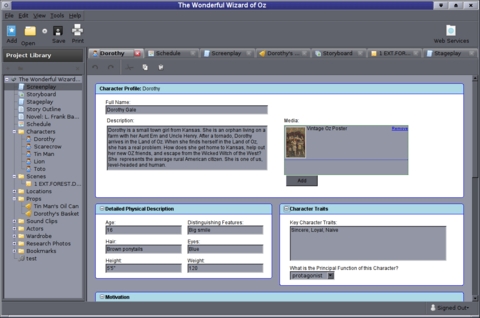

This ability to organize different items hierarchically doesn't stop with the text sheets—a number of writing aids are available for adding to the pile and to make organization easier. For example, detailed forms for creating character dossiers are included. The forms have fields for everything you'd expect, and a few things you wouldn't—physical description, a graphics field for a photo or concept sketch, the role(s) that the character plays in the drama, motivations, goals, family background, education, habits and vices, and likes and dislikes.

Figure 3. A character dossier from CeltX's “Wizard of Oz” sample project—notice the hierarchical project tree in the sidebar to the left.

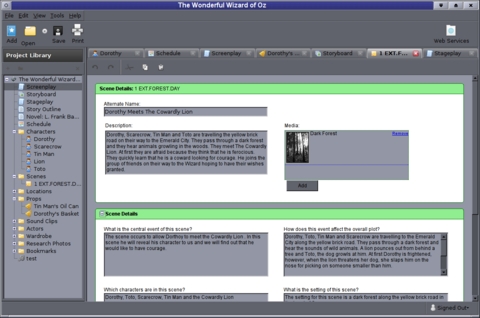

Similar forms are available for building detailed scene descriptions from one's notes, listing out setting, duration, protagonist/antagonist relationships, and the description of the action and character development that must happen in the scene. Because CeltX is based on Mozilla, it includes things like a tabbed interface that lets users keep their relevant character dossiers, scene descriptions, text snippets and scripts open side by side, so that they can reference notes and dossiers quickly while working on the script proper. Used to their full advantage, good writers can plan the entire film except for the spoken dialogue before they ever begin the actual script, and then easily refer to those notes during composition.

Figure 4. The scene element, which actually continues on for quite a bit longer than can fit in a screenshot. All of CeltX's description elements are similarly thorough.

When it comes to the work of actually creating the script, CeltX does a marvelous job. Built-in templates for the four major types of scripts in common usage are included: Screenplays, Stage Plays, Radio Plays and A/V scripts (these are used for advertisements and other narrated visual media). Adding one of these (or a number of them) to any point in the project is a two-click enterprise and very straightforward.

Once inside the script editing module proper, users have the option of typing into the template, which formats things properly on the fly, or using the index cards outlining feature—something veteran script writers will find very useful.

In the old days when we had to work by hand or wrestle with word processor templates, a lot of screenwriters would begin by scribbling one- to two-sentence scene descriptions on index cards and sticking them to a corkboard. We'd then rearrange things until we got a dramatic structure that seemed to work, and then use the order we settled on as the rough outline for the script. CeltX made good use of this paper-world convention by including an Index Cards screen for laying out the scenes and shuffling them around into the correct order before diving in and writing the dialogue. The shuffling feature continues to work after the script has been written, making post hoc rearrangement of the script a breeze. Once the writing is done, the script can be exported to PDF or HTML, retaining its proper formatting, or to plain text (which, alas, loses much of the formatting).

However, CeltX is not merely a tricked-out word processor. It aims to be a full-fledged preproduction suite, and it succeeds famously. It has forms for describing every prop, every set design, every location, every piece of lighting and camera equipment, and every actor. Further forms are available for greenery, practical effects, explosives, digital effects, production vehicles, character vehicles, animals, craft services, and just about everything else a body could ever need to produce a motion picture, stage play or other performing arts piece. Using these forms to annotate the script, it's very simple to create a production breakdown—the first step toward budgeting and scheduling a project for shooting.

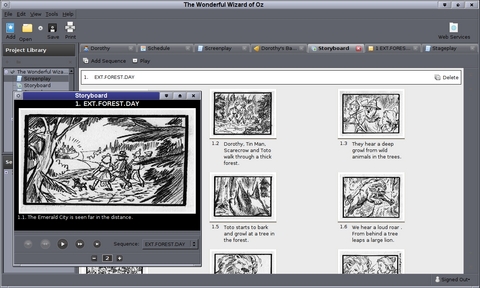

Although CeltX does not contain a budgeting system, it does contain a calender for production scheduling, as well as a couple other invaluable tools for pushing the production forward. Planning a project for production has a long and detailed set of challenges, not the least of which is the translation of the written word into visual images. To this end, filmmakers have traditionally employed storyboards.

Storyboards are, for lack of a better description, a comic-book version of the screenplay drawn up from directions contained in the script. The camera angles, movement and editing are planned out in as detailed a manner as possible (usually with the input of the director and the director of photography), and these storyboards are then used in the budget breakdown—the planned camera angles and motion help the photography directors ascertain the equipment (lenses, dollies, steadicams, cranes and so forth) that they'll need to shoot the film successfully. The storyboards also often are taken on set to guide the director of photography as the film is shot to make sure the production team covers all the proper camera angles and performances.

CeltX contains a very usable storyboarding module. A storyboard can be constructed with imported images (scanned illustrations, photographs from rehearsals or what have you) on a per-sequence basis, and then played back in an included flipbook to give the approximation of an animatic, helping the director get a feel for the timing of a scene before it's shot.

Of course, CeltX is a commercial enterprise, and its business model revolves around a raft of Web services that it offers through CeltX Project Central. Although the CeltX folks intend to add premium features as the user base grows, the basic membership is free, and for that freedom, users get quite a powerful program. By signing up for the account, users have the option of creating a private or a public publishing account. A public account lets users show their script to the CeltX community to solicit comments and compare notes, while a private account shared among a small group allows for group collaboration on the script and production breakdown.

If, for example, your storyboard artist, producer or client, and your director need to work together on a production breakdown, each can be given access to the project. The director can annotate the script and the storyboard cells that the storyboard artist draws, the producer can give notes for the screenplay content and budget, and they can collaborate on revisions and breakdown in real time (or in delayed time ad hoc, which is much more convenient). This kind of collaboration reduces the number of necessary production meetings and greatly facilitates the collaborative process—and it, like the software, is free.

I should emphasize, however, that one need not be a member at CeltX Project Central in order to use CeltX in-house, or to export its results to open formats. Membership at Project Central is both free and optional—it's a value-added service for CeltX users, not a lock-in tactic, which makes it the best of all worlds.

Now, the coup de grace. All of the additional elements, including storyboards and music, can be used to mark up the script. By referencing these elements in the script, everything is tied together for producing production breakdown reports on a scene-by-scene basis, giving the prospective producer and director everything they need to produce a film (other than the actual money, personnel and equipment).

There are times when those of us determined to travel in the land of open source must settle for “good enough”. This is particularly the case in the realm of multimedia production. With CeltX, that's not the case. By combining several industry-standard document template formats with a well thought-out preproduction system offering thorough production breakouts and top-rate reports, CeltX has leapt right to the head of the pack. My only regret is that there isn't a basic book template included, as many of the included tools also are indispensable to novelists, and I'd very much like to use it for my next book. However, its open nature means that the document templates are editable. Now, if I could just learn the XML API it uses, perhaps I could extend the capabilities of this system just a little bit further.

Excuse me, I believe I have some software modification to do.

Dan Sawyer is the founder of ArtisticWhispers Productions (www.artisticwhispers.com), a small audio/video studio in the San Francisco Bay Area. He has been an enthusiastic advocate for free and open-source software since the late 1990s, when he founded the Blenderwars filmmaking community (www.blenderwars.com). He currently is the host of “The Polyschizmatic Reprobates Hour”, a cultural commentary podcast, and “Sculpting God”, a science-fiction anthology podcast. Author contact information is available at www.jdsawyer.net.