Implement Port-Knocking Security with knockd

When dealing with computer security, you should assume that hackers will be trying to get in through any available doors your system may have, no matter how many precautions you might have taken. The method of allowing entrance depending on a password is a classic one and is widely used. In order to “open a door” (meaning, connect to a port on your computer), you first have to specify the correct password. This can work (provided the password is tough enough to crack, and you don't fall prey to many hacking attacks that might reveal your password), but it still presents a problem. The mere fact of knowing a door exists is enough to tempt would-be intruders.

So, an open port can be thought of as a door with (possibly) a lock, where the password works as the key. If you are running some kind of public service (for example, a Web server), it's pretty obvious that you can't go overboard with protection; otherwise, no one will be able to use your service. However, if you want to allow access only to a few people, you can hide the fact that there actually is a door to the system from the rest of the world. You can “knock intruders away”, by not only putting a lock on the door, but also by hiding the lock itself! Port knocking is a simple method for protecting your ports, keeping them closed and invisible to the world until users provide a secret knock, which will then (and only then) open the port so they can enter the password and gain entrance.

Port knocking is appropriate for users who require access to servers that are not publicly available. The server can keep all its ports closed, but open them on demand as soon as users have authenticated themselves by providing a specific knock sequence (a sort of password). After the port is opened, usual security mechanisms (passwords, certificates and so on) apply. This is an extra advantage; the protected services won't require any modification, because the extra security is provided at the firewall level. Finally, port knocking is easy to implement and quite modest as far as resources, so it won't cause any overloads on the server.

In this article, I explain how to implement port knocking in order to add yet another layer to your system security.

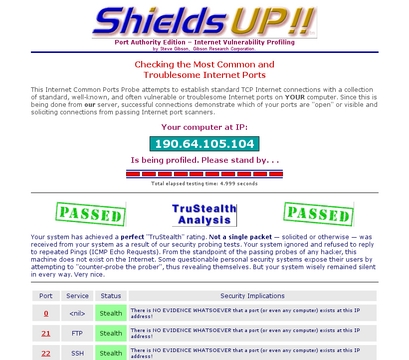

Would-be hackers cannot attack your system unless they know which port to try. Plenty of port-scanning tools are available. A simple way to check your machine's security level is by running an on-line test, such as GRC's ShieldsUp (Figure 1). The test results in Figure 1 show that attackers wouldn't even know a machine is available to attack, because all the port queries were ignored and went unanswered.

Figure 1. A completely locked-up site, in “stealth” mode, doesn't give any information to attackers, who couldn't even learn that the site actually exists.

Another common tool is nmap, which is a veritable Swiss Army knife of scanning and inspection options. A simple nmap -v your.site.url command will try to find any open ports. Note that by default, nmap checks only the 1–1000 range, which comprises all the “usual” ports, but you could do a more thorough test by adding a -p1-65535 parameter. Listing 1 shows how you can rest assured that your site is closed to the world. So, now that you know you are safe, how do you go about opening a port, but keep it obscured from view?

Listing 1. The standard nmap port-scanning tool provides another confirmation that your site and all ports are completely closed to the world.

$ nmap -v -A your.site.url Starting Nmap 4.75 ( https://nmap.org ) at 2009-10-03 12:59 UYT Initiating Ping Scan at 12:59 Scanning 190.64.105.104 [1 port] Completed Ping Scan at 12:59, 0.00s elapsed (1 total hosts) Initiating Parallel DNS resolution of 1 host. at 12:59 Completed Parallel DNS resolution of 1 host. at 12:59, 0.01s elapsed Initiating Connect Scan at 12:59 Scanning r190-64-105-104.dialup.adsl.anteldata.net.uy (190.64.105.104) [1000 ports] Completed Connect Scan at 12:59, 2.76s elapsed (1000 total ports) Initiating Service scan at 12:59 SCRIPT ENGINE: Initiating script scanning. Host r190-64-105-104.dialup.adsl.anteldata.net.uy (190.64.105.104) appears to be up ... good. All 1000 scanned ports on r190-64-105-104.dialup.adsl.anteldata.net.uy (190.64.105.104) are closed Read data files from: /usr/share/nmap Service detection performed. Please report any incorrect results at https://nmap.org/submit/ . Nmap done: 1 IP address (1 host up) scanned in 2.94 seconds

The idea behind port knocking is to close all ports and monitor attempts to connect to them. Whenever a very specific sequence of attempts (a knock sequence) is recognized, and only in that case, the system can be configured to perform some specific action, like opening a given port, so the outsider can get in. The knock sequence can be as complex as you like—for example, a simple list (like trying TCP port 7005, then TCP port 7006 and finally, TCP port 7007) to a collection of use-only-once sequences, which once used, will not be allowed again. This is the equivalent of “one-time pads”, a cryptography method that, when used correctly, provides perfect secrecy.

Before setting this up, let me explain why it's a good safety measure. There are 65,535 possible ports, but after discarding the already-used ones (see the list of assigned ports in Resources), suppose you are left with “only” 50,000 available ports. If attackers have to guess a sequence of five different ports, there are roughly 312,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 possible combinations they should try. Obviously, brute-force methods won't help! Of course, you shouldn't assume that blind luck is the only possible attack, and that's why port knocking ought not be the only security measure you use, but just another extra layer for attackers to go through (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Would-be attackers (top) are simply rejected by the firewall, but when a legit user (middle) provides the correct sequence of “knocks”, the firewall (bottom) allows access to a specific port, so the user can work with the server.

On the machine you are protecting, install the knockd dæmon, which will be in charge of monitoring the knock attempts. This package is available for all distributions. For example, in Ubuntu, run sudo apt-get install knockd, and in OpenSUSE, run sudo zypper install knockd or use YaST. Now you need to specify your knocking rules by editing the /etc/knockd.conf file and start the dæmon running. An example configuration is shown in Listing 2. Note: the given iptables commands are appropriate for an OpenSUSE distribution running the standard firewall, with eth0 in the external zone; with other distributions and setups, you will need to determine what command to use.

Listing 2. A simple /etc/knockd.conf file, which requires successive knocks on ports 7005, 7007 and 7006 in order to enable secure shell (SSH) access.

[opencloseSSH]

sequence = 7005,7006,7007

seq_timeout = 15

tcpflags = syn

start_command = /usr/sbin/iptables -s %IP% -I input_ext 1

↪-p tcp --dport ssh -j ACCEPT

cmd_timeout = 30

stop_command = /usr/sbin/iptables -s %IP% -D input_ext

↪-p tcp --dport ssh -j ACCEPT

You probably can surmise that this looks for a sequence of three knocks—7005, 7006 and 7007 (not very safe, but just an example)—and then opens or closes the SSH port. This example allows a maximum timeout for entering the knock sequence (15 seconds) and a login window (30 seconds) during which the port will be opened. Now, let's test it out.

First, you can see that without running knockd, an attempt to log in from the remote machine just fails:

$ ssh your.site.url -o ConnectTimeout=10 ssh: connect to host your.site.url port 22: Connection timed out

Next, let's start the knockd server. Usually, you would run it as root via knockd -d or /etc/init.d/knockd start; however, for the moment, so you can see what happens, let's run it in debug mode with knock -D:

# knockd -D

config: new section: 'opencloseSSH'

config: opencloseSSH: sequence: 7005:tcp,7006:tcp,7007:tcp

config: opencloseSSH: seq_timeout: 15

config: tcp flag: SYN

config: opencloseSSH: start_command:

/usr/sbin/iptables -s %IP% -I input_ext 1

-p tcp --dport ssh -j ACCEPT

config: opencloseSSH: cmd_timeout: 30

config: opencloseSSH: stop_command:

/usr/sbin/iptables -s %IP% -D input_ext

-p tcp --dport ssh -j ACCEPT

ethernet interface detected

Local IP: 192.168.1.10

Now, let's go back to the remote machine. You can see that an ssh attempt still fails, but after three knock commands, you can get in:

$ ssh your.site.url -o ConnectTimeout=10 ssh: connect to host your.site.url port 22: Connection timed out $ knock your.site.url 7005 $ knock your.site.url 7006 $ knock your.site.url 7007 $ ssh your.site.url -o ConnectTimeout=10 Password: Last login: Sat Oct 3 14:58:45 2009 from 192.168.1.100 ...

Looking at the console on the server, you can see the knocks coming in:

2009-09-03 15:29:47:

tcp: 190.64.105.104:33036 -> 192.168.1.10:7005 74 bytes

2009-09-03 15:29:50:

tcp: 190.64.105.104:53783 -> 192.168.1.10:7006 74 bytes

2009-09-03 15:29:51:

tcp: 190.64.105.104:40300 -> 192.168.1.10:7007 74 bytes

If the remote sequence of knocks had been wrong, there would have been no visible results and the SSH port would have remained closed, with no one the wiser.

The config file /etc/knockd.conf is divided into sections, one for each specific knock sequence, with a special general section, options, for global parameters. Let's go through the general options first:

You can log events either to a specific file by using LogFile=/path/to/log/file, or to the standard Linux log files by using UseSyslog. Note: it's sometimes suggested that you avoid such logging, because it enables an extra possible goal for attackers—should they get their hands on the log, they would have the port-knocking sequences.

When knockd runs as a dæmon, you may want to check whether it's still running. The PidFile=/path/to/PID/file option specifies a file into which knockd's PID (process ID) will be stored. An interesting point: should knockd crash, your system will be safer than ever—all ports will be closed (so safer) but totally unaccessible. You might consider implementing a cron task that would check for the knockd PID periodically and restart the dæmon if needed.

By default, eth0 will be the observed network interface. You can change this with something like Interface=eth1. You must not include the complete path to the device, just its name.

Every sequence you want to recognize needs a name; the example (Listing 2) used just one, named openclosessh. Options and their parameters can be written in upper-, lower- or mixed case:

Sequence is used to specify the desired series of knocks—for example, 7005,7007:udp,7003. Knocks are usually TCP, but you can opt for UDP.

One_Time_Sequences=/path/to/file allows you to specify a file containing “use once” sequences. After each sequence is used, it will be erased. You just need a text file with a sequence (in the format above) in each line.

Seq_Timeout=seconds.to.wait.for.the.knock is the maximum time for completing a sequence. If you take too long to knock, you won't be able to get in.

Start_Command=some.command specifies what command (either a single line or a full script) must be executed after recognizing a knock sequence. If you include the %IP% parameter, it will be replaced at runtime by the knocker's IP. This allows you, for example, to open the firewall port but only for the knocker and not for anybody else. This example uses an iptables command to open the port (see Resources for more on this).

Cmd_Timeout=seconds.to.wait.after.the.knock lets you execute a second command a certain time after the start command is run. You can use this to close the port; if the knocker didn't log in quickly enough, the port will be closed.

Stop_Command=some.other.command is the command that will be executed after the second timeout.

TCPFlags=list.of.flags lets you examine incoming TCP packets and discard those that don't match the flags (FIN, SYN, RST, PSH, ACK or URG; see Resources for more on this). Over an SSH connection, you should use TCPFlags=SYN, so other traffic won't interfere with the knock sequence.

For the purposes of this example (remotely opening and closing port 22), you didn't need more than a single sequence, shown in Listing 2. However, nothing requires having a single sequence, and for that matter, commands do not have to open ports either! Whenever a knock sequence is recognized, the given command will be executed. In the example, it opened a firewall port, but it could be used for any other functions you might think of—triggering a backup, running a certain process, sending e-mail and so on.

The knockd command accepts the following command-line options:

-c lets you specify a different configuration file, instead of the usual /etc/knockd.conf.

-d makes knockd run as a dæmon in the background; this is the standard way of functioning.

-h provides syntax help.

-i lets you change which interface to listen on; by default, it uses whatever you specify in the configuration file or eth0 if none is specified.

-l allows looking up DNS names for log entries, but this is considered bad practice, because it forces your machine to lose stealthiness and do DNS traffic, which could be monitored.

-v produces more verbose status messages.

-D outputs debugging messages.

-V shows the current version number.

In order to send the required knocks, you could use any program, but the knock command that comes with the knockd package is the usual choice. An example of its usage is shown above (knock your.site.url 7005) for a TCP knock on port 7005. For a UDP knock, either add the -u parameter, or do knock your.site.url 7005:udp. The -h parameter provides the (simple) syntax description.

If You Are behind a Router

If you aren't directly connected to the Internet, but go through a router instead, you need to make some configuration changes. How you make these changes depends on your specific router and the firewall software you use, but in general terms you should do the following:

1) Forward the knock ports to your machine, so knockd will be able to recognize them.

2) Forward port 22 to your machine. Although in fact, you could forward any other port (say, 22960) to port 22 on your machine, and remote users would have to ssh -p 22960 your.site.url in order to connect to your machine. This could be seen as “security through obscurity”—a defense against script kiddies, at least.

3) Configure your machine's firewall to reject connections to port 22 and to the knock ports:

$ /usr/sbin/iptables -I INPUT 1 -p tcp --dport ssh -j REJECT $ /usr/sbin/iptables -I INPUT 1 -p tcp --sport 7005:7007 -j REJECT

The command to allow SSH connections would then be:

$ /usr/sbin/iptables -I INPUT 1 -p tcp --dport ssh -j ACCEPT

And, the command for closing it again would be:

$ /usr/sbin/iptables -D INPUT -p tcp --dport ssh -j ACCEPT

Port knocking can't be the only security weapon in your arsenal, but it helps add an extra barrier to your machine and makes it harder for hackers to get a toehold into your system.

Resources

The knockd page is at www.zeroflux.org/projects/knock, and you can find the knockd man page documentation at linux.die.net/man/1/knockd, or simply do man knockd at a console.

For more on port knocking, check www.portknocking.org/view, and in particular, see www.portknocking.org/view/implementations for several more implementations. Also, you might check the critique at www.linux.com/archive/articles/37888 and the answer at www.portknocking.org/view/about/critique for a point/counterpoint argument on port knocking.

Read en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transmission_Control_Protocol for TCP flags, especially SYN. At www.faqs.org/docs/iptables/tcpconnections.html, you can find a good diagram showing how flags are used.

Port numbers are assigned by IANA (Internet Assigned Numbers Authority); see www.iana.org/assignments/port-numbers for a list.

To test your site, get nmap at nmap.org, and also go to GRC's (Gibson's Research Corporation) site at https://www.grc.com, and try the ShieldsUp test.

Check www.netfilter.org if you need to refresh your iptables skills.

Federico Kereki is an Uruguayan Systems Engineer, with more than 20 years' experience teaching at universities, doing development and consulting work, and writing articles and course material. He has been using Linux for many years now, having installed it at several different companies. He is particularly interested in the better security and performance of Linux boxes.