Cooking with Linux - My Desktop Lies over the Ocean

You have been on the phone for an hour, François, and it is nearly time for our guests to arrive. Who are you talking to? Your cousin in Riviere-du-Loup? And, you're helping her with her Linux system? That is commendable, mon ami, but we have work to do. Yes, I realize it takes a great deal of time when you have to ask the other person to describe what she sees while you try to tell her what she should do next. It might be easier to demonstrate. Yes, I know she lives a few hundred kilometers away. With your Linux system and the right tools, being there doesn't have to mean hours and hours of driving. Wrap up your call quickly, and you'll learn everything you need to know when I serve up today's menu. Vite! Our guests are arriving as we speak.

Welcome, everyone, to Chez Marcel. It is a great pleasure to have you here, where fine Linux and open-source software meets great wine. Please, sit, while my faithful waiter takes a short trip to the wine cellar. François, please bring back the Collavini 2005 Villa Canlungo Pinot Grigio. Quickly, mon ami.

It only makes sense that being there, in person, to show somebody how to work with his or her system isn't always convenient. Taking control of an existing remote desktop session lets you work with the desktop as though you were there, without having to walk up a floor or drive several hundred miles. In that respect, it's not only a time-saver, but also environmentally-friendly (imagine having to fly overseas). Another great incentive for remote control is the office environment. Do you need to show users how to add an icon to their desktops? Connect to their desktops and let them watch. Have you received a call asking for help interpreting an error message? Connect to the system and ask the user to re-create the scenario while you watch. The possibilities are endless. Taking control of a remote desktop also provides everyone with a learning experience. For you, the person doing the teaching, it lets users show exactly how whatever went wrong, went wrong. For users, it lets them watch a master at work, so they too can learn the ways of Linux. This remote control is probably better referred to as desktop sharing.

Excellent, François has returned with the wine. Mon ami, after you have taken care of filling our guests' glasses, please take care of mine as well.

Both of the most popular Linux desktop environments—KDE and GNOME—come equipped with excellent solutions for desktop sharing. With these tools, users can invite someone either to watch their desktop session or take control of it. In an office environment, system administrators also can set it up so they can take control whenever necessary. Let's start this tour with the KDE desktop sharing application.

On my Kubuntu Linux system, remote desktop sharing is under the Internet menu. The command name is krfb, if you want to start it directly using your Alt-F2 run dialog. When you do so, a window labeled Invitation - Krfb appears (Figure 1).

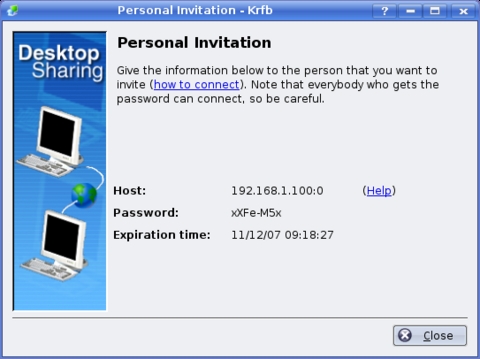

The window offers you three important choices. You can create either a New Personal Invitation or Invite via Email. The third button provides a more complex interface that allows you access to invitations that already have been created. You can delete existing invitations or create new personal invitations. There's also a Configure button at the bottom—a button that is of particular importance to system administrators. Let's leave those things for now and concentrate on creating a personal invitation. To do that, click the Create Personal Invitation button, and a window labeled Personal Invitation - Krfb appears (Figure 2).

For security reasons, the invitation itself lasts only an hour. If you don't do anything else, Desktop Sharing automagically comes up with a password and an expiration time for the session. The host address necessary for the connection also is displayed. Overriding either the password or the expiration time is not allowed. Make sure you pass on the information as it is shown to the person who will be connecting. When you have passed on the information (or written it down), click Close.

Note:

The IP address displayed may be an issue if you are trying to connect to a remote system that is on the other side of a home router or firewall. In those instances, you may need to set up a port redirect to allow port 5900 to connect to the PC you need to access. Because the way to do this varies from ISP to ISP and router manufacturer to router manufacturer, there isn't a quick way to explain it here. Your router documentation should cover this.

The other option is an e-mail invitation, which is essentially the same thing, except the connection details are sent via e-mail rather than read over the phone. The only catch here is that you are sending the means to access your system via e-mail during that one-hour period. If you choose this option, you'll receive a warning about plain-text e-mail over the Internet and the wisdom of encrypting said e-mail. Click Continue to get past the warning, and a KMail message appears (with instructions on how to connect), ready for you to click Send. If no one answers the invitation, it disappears within an hour.

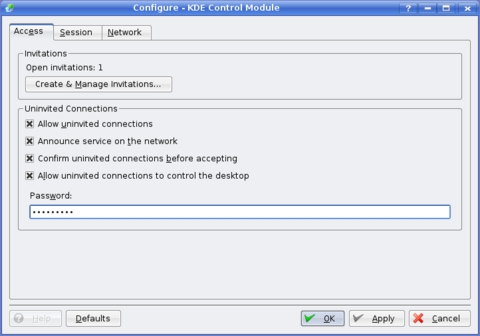

Before we move on, click Close to get past all those invitations, and we'll have a look at another means of providing access—uninvited connections (that's our mysterious Configure button). If sending an e-mail invitation presents interesting security concerns, a wide-open, permanent invitation should ring additional bells. Nevertheless, in an office environment, it also may be the sanest method of giving yourself access. Click the Configure button to bring up the Configure dialog from the KDE Control Centre (Figure 3). Yes, that is correct. This configuration dialog also is available by running the KDE Control Centre from the K menu (or by using the kcontrol command name) and looking under the Internet & Network menu for Desktop Sharing.

If you check the Allow uninvited connections box, you still have to assign a password for connecting. Furthermore, you have the opportunity to “Confirm uninvited connections before accepting”. You also can decide whether to give those uninvited connections the ability to control the desktop. If you don't check the latter, users can give you control at any time by selecting the desktop sharing icon that appears in their system tray.

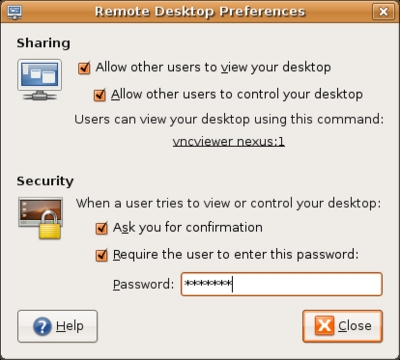

On the GNOME side of things, there's a program called Remote Desktop Sharing. On a typical GNOME setup, click System on the top menu bar, then look under Preferences for Remote Desktop (if you like, you can run the command directly using /usr/lib/vino/vino-server). The Remote Desktop Preferences menu appears as shown in Figure 4. Needless to say, I love the name.

Figure 4. GNOME's remote desktop invitation is run by a command named vino-server. Suddenly, I'm thirsty.

Some of this is going to look very familiar, because many of the questions mirror those of the KDE Control Centre configuration for desktop sharing. If you simply want to show what your desktop is doing (and let somebody follow along), click the Allow other users to view your desktop check box. If you are looking for help, or you want to help the person on the other end, make sure the person sharing checks the Allow box, second from the top. Users who want to leave a sharing session open all the time may decide to check the Ask you for confirmation button, so that a remote user has to have their permission. Finally, if this is an unattended connection, you'll surely want to assign a password to allow this connection to happen. Although it may not seem apparent here, you also can generate an e-mail invitation by clicking the command listed under Users can view your desktop using this command.

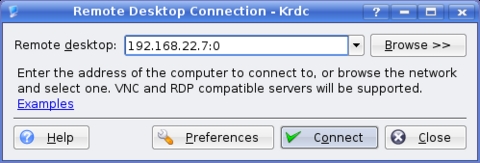

To connect to a remote shared desktop, you can use any VNC client—the GNOME vino-server program suggests vncviewer as the command to use—including a Java-enabled browser. The invitation e-mail tells you how to do this. The slicker, desktop-oriented way to do this is by using the tools provided by your desktop environment. The KDE Remote Desktop Connection program (Krdc) can be started from the Internet K Menu, where you'll see it listed as Remote Desktop Connection. From the dialog that pops up, you can enter the host connection information as shown in Figure 5.

The connection program can be used simply by entering the sharing host's address and pressing Connect. Another window appears asking you to specify the quality of your connection—whether it be a fast LAN connection, a slow dial-up connection or something in between. When you do connect, what happens depends on how the invitation was created. If the confirm option was set, a warning message appears on the remote desktop asking for confirmation. On the client side, you then may be asked for a password.

Note:

KDE client programs can connect to GNOME desktops and vice versa.

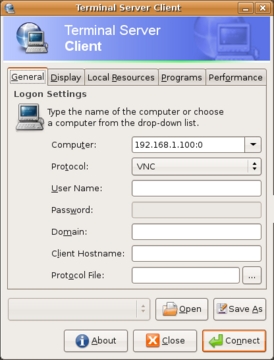

On the GNOME side of things, remote connections are done with the Terminal Server Client program (Figure 6). You'll find it under Applications in the Internet menu, but you also can run it directly with tsclient.

The Terminal Server Client has five tabs, the most important of which is the General tab. Enter the remote computer's address (including the :0 display extension as shown by the desktop sharing server program), and make sure you select VNC as the protocol from the drop-down list. For these remote desktop sessions, you simply can click Connect and be done. As with the KDE client, the remote user may need to confirm the session (which may require you to enter a password) and then manually give you control of the mouse and keyboard. The additional tabs allow you to define your display size, set color depth or modify some performance-related parameters. Incidentally, both the KDE remote client and the GNOME Terminal Server Client also let you connect to an RDP session as well.

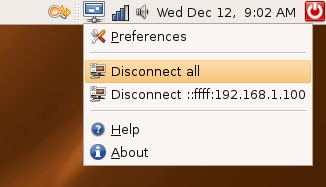

Once a session is open, a tray icon appears in your system tray. The GNOME icon looks like a small terminal screen (Figure 7), and the default KDE tray icon (Figure 8) looks like a screen with a globe in front of it. In both cases, you can right-click on the tray icon where a drop-down or pop-up menu will show you active connections and give you a means to terminate them.

Figure 7. The GNOME Desktop Sharing Tray Icon with Drop-Down Menu

Figure 8. The KDE desktop sharing system tray icon (top right next to the clock) lets you manage connections and desktop control.

Once you have established a connection, the remote system becomes a window on your current desktop. You can switch to full-screen mode, or as is the case with the KDE client, you can drag the window to any size you desire, then click the Scale button to resize the remote control session dynamically (Figure 9).

Despite the many advantages of doing things at a distance, there is only one way to enjoy a glass of wine, and that is by being there. Luckily, François, our most excellent waiter, is not elsewhere, but right here in this restaurant. As the clock ticks ever closer to closing time, I'm sure we can convince him to let us enjoy a little more wine before we head to our respective homes. If you please, François, make sure everyone's glass is refilled. Raise your glasses, mes amis, and let us all drink to one another's health. A votre santé! Bon appétit!

Resources

Marcel's Web Site: www.marcelgagne.com

The WFTL-LUG, Marcel's Online Linux User Group: www.marcelgagne.com/wftllugform.html

Marcel Gagné is an award-winning writer living in Waterloo, Ontario. He is the author of the Moving to Linux series of books from Addison-Wesley. He also makes regular television appearances as Call for Help's Linux guy and every month on radio's Computer America show. Marcel is also a pilot, a past Top-40 disc jockey, writes science fiction and fantasy, and folds a mean Origami T-Rex. He can be reached via e-mail at mggagne@salmar.com. You can discover lots of other things (including great Wine links) from his Web site at www.marcelgagne.com.