Privacy, Mine: the Right of Individual Persons, Not of the Data

“For true, lasting privacy, we must shift from the ‘privacy policies’ of companies, which spring from data protection laws, to the ‘privacy’ of individual persons, as contemplated by human rights laws.”

How do we accomplish this shift?

TL;DR (in summary)

- Privacy pertains to the person; “privacy” is the state of being free from public attention and unwanted intrusion.

- Data is not privacy, but data from or about a person can be private or not private depending on how it’s used, who is using it and who has control of it.

- In the digital world, a person’s privacy policy is like the clothing that one puts on to signal what data they consider private and what is not private.

- The companies (sites, apps and so on) that respect a person’s privacy will build relationships with that person over time.

- The accumulation of trust over time incentivizes good behavior by both parties, to preserve value and not lose it instantly.

We live in the age of surveillance marketing, where consumers’ privacy is being violated without their knowledge, consent or recourse. Data from and about consumers is collected en masse by ad-tech companies and traded for profit. But few consumers knew about it until things blow up like the Cambridge Analytica/Facebook scandal. Most consumers think they are interacting with the sites they’re visiting or the apps (like Facebook) they’re using, but they aren't aware of the dozens of hidden ad-tech trackers that siphon their data off to other places or the aggressive data collection and cross-device tracking of apps. Not only are they not aware, they also definitely did not give consent to third parties to use, buy and sell their data. They wouldn’t even know who ABCTechCompany was anyway if it asked for consent.

Consent Is Not the Same as Permission, But Consumers Are Tricked Anyway

Consumers are asked to agree to privacy policies on the sites they visit and the apps they use—that is, give consent to the companies’ handling of their data. But it’s common knowledge, backed by academic research, that online privacy policies are too byzantine for anyone to understand. So basically consumers have no choice if they want to move on—they are forced to click “accept” to the terms of the privacy policy without reading it. In fact, by some estimates, if everyone in the country actually read online privacy policies, it would eat up 54 billion hours a year, equivalent to almost $800 billion in time spent (at $15/hr).

Further, consumers may not have given permission to various companies to use their data, if they truly understood the legalese and appreciated the implications and consequences of agreeing to it. Social justice activist Renee Lloyd sums up the current situation in this way, “[Even though] the Privacy Policy is required to disclose the use of the data; [and] the terms of service is the means of consent, the current (non-GDPR) context Privacy Policies suffer from using broad language like ‘improving products’ to cover uses that may or may not be agreeable to the customer. The terms of service or other ‘contract’ is the place where consent is allegedly granted, rights are transferred and liabilities transferred. They are written in legalese making it nearly impossible for the customer to understand.”

John Wunderlich further warns, “we need to be careful not to accept the faux ‘notice and consent’ paradigm. This can lead to a form of victim blaming. Users should no more be expected to read, understand, and agree to all the privacy policies and consent notices that apply to their data on a daily basis than they should be required to be a qualified automobile mechanic who understands the inner workings of their car before they drive it.” Michelle De Mooy says “[the current] ‘notice and consent’ is designed to be swatted away, clicked on, and forgotten. It is privacy theater, not privacy.”

Also see NYTimes: How Silicon Valley Puts the ‘Con’ in Consent: “If no one reads the terms and conditions, how can they continue to be the legal backbone of the internet?”

Privacy Is Not Data Privacy, But the Two Often Get Confused and Conflated

Elizabeth Renieris (@hackylawyER) emphasizes a key distinction between privacy and data privacy (see On personal data)—the person is different from the data from or about the person. “Privacy has to do with the individual person not the data, which is why it's typically a right found in human rights laws, constitutions, etc., and not in regulations, such as data protection laws. If we only focus on the data, we lose sight of the person and their fundamental rights. Moreover, there is no such thing as ‘private’ data under data protection law, which presumes the data has been shared—and now needs protection. We risk giving up the whole notion of privacy if we only focus on the data.” Ultimately, it’s the privacy of the person, not the privacy of the data that matters. Furthermore, some types of data may be private or not private, depending on how it’s being used or who is using it, as I will analyze below.

Guy Jarvis adds, “Protecting data, rather than privacy, ensures privacy is always lost and up for sale, a commodity of value rather than a basic human right.” The data collected by ad-tech companies, along with the “privacy policies” written to protect them, is how the “Badtech Industrial Complex” continues to profit off consumers. The privacy nightmare rolls on for the individual person, who may not even realize it’s a nightmare.

Surveillance Marketing Is What Caused the Current Privacy Nightmare

Ad tech has convinced marketers that “more data is better”—that having more data about users means better marketing. The promise of being able to target the right person at the right time with the right ad is what led to the development of the data collection machinery of ad tech and the privacy policies that go with that. But what we call digital marketing today is merely a euphemism for surveillance marketing. As explained in this article, "What Is Surveillance Capitalism? And How Did It Hijack the Internet?" ad tech was built on the triple myths of 1) the long tail, 2) behavioral targeting and 3) hypertargeting. It’s not even clear whether any of these actually drive more business outcomes. On the contrary, there is evidence that it doesn’t work. For example, P&G cut $200 million from its digital budgets and saw no change in business outcomes; Chase reduced the number of sites that showed its ads from 400,000 to 5,000 (a 99% decrease) and saw no difference in business outcomes.

Consider an alternate universe.

What if all this data collected by ad tech were not necessary? What if surveillance marketing was no better than good old-fashioned marketing. That’s hard to imagine, given the euphoria around ad tech companies with valuations in the billions of dollars but revenues that would be considered vaporware in every sense of the word. The surveillance marketing that caused this privacy nightmare would evaporate when the sunlight of common sense shone on it. If you eliminate surveillance marketing, you eliminate the privacy nightmare that it created. How do we accomplish that?

Turn That Privacy Frown Upside Down, with a Privacy Policy of the Person

To take a step toward this better future, let’s flip the current notion of privacy upside down. Currently, privacy is what ad-tech companies think it should be. Consumers see 100 different privacy policies when they visit 100 different sites. These policies are written by the ad-tech company lawyers to enable them to collect and use customers’ data and protect them from any liability arising from such use. Consumers are forced to consent to them, even though 100% of them don’t understand the legalese anyway.

What if we flipped this notion of privacy on its head? What if there was one privacy policy instead—the privacy policy of the individual. Every site that the person visits would have to consent to it, instead of the other way around. If the site respects the user’s privacy policy, then the user transacts with it and may even consider a longer term relationship with the site. A person’s privacy policy as opposed to sites’ or companies’ privacy policies is exactly what is contemplated by CustomerCommons.org.

The dictionary says “privacy is the state of being free from public attention or unsanctioned intrusion.” Privacy pertains to the person, not the data. So as long as individuals can set preferences for how their data or data about them is accessed and used, individuals can protect their own privacy. Doc Searls likes to put it this way, “just like humans wear clothing in the physical world to signal what they consider private or not private, in the digital world, the person’s own privacy policy is the virtual clothing they use to signal what data is private or not private.” Ad-tech companies’ interests are to maximize their own revenues, so they would be the worst (most conflicted) guardians of individuals’ privacy. Individuals are the best protectors of their own privacy—and they do so by controlling their data, determining what is private or not private. How do they do this?

Some Data Comes from the Person; Other Data Is about That Person

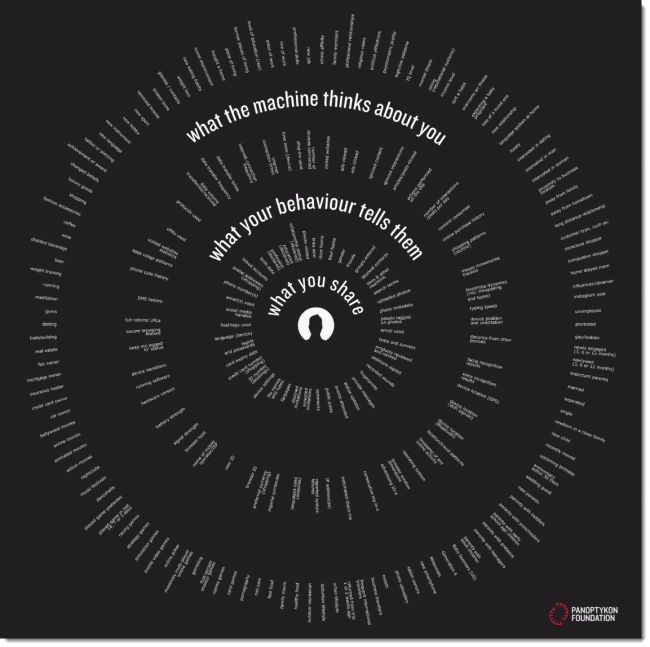

The following chart neatly shows three categories of data: 1) what you share, 2) what your behavior tells others and 3) what the machine thinks about you. The second and third categories are not even the personal data of individual persons; they are derived by third parties through data collection—that is, what sites they visit, what they search for, who they are friends with and so on. Most of this information is beyond the control of individuals, because they literally don’t know who is collecting it and what they will do with it. And those third-party ad-tech companies that collected it have no relationship with the individuals, so it’s not even possible for them to ask for consent. But if the privacy policy is that of the individual, and companies must agree to its terms to the handling, usage and sale of said data, then all of the above is solved.

Source: https://panoptykon.org/sites/default/files/3levels.png

The Privacy Policy of the Person Requires Tools to Enforce

People can specify their preferences with a privacy policy, but they also need technology tools to help them enforce it. These tools cannot be supplied by ad-tech companies or any other company that can be paid off by ad tech. For example, Google offers a free browser Chrome, a free mobile operating system Android, free email with Gmail, and other services—all of these were created to help Google collect data from every possible aspect of consumers’ lives. Facebook built or bought Instagram and WhatsApp to do the same. Consumers downloaded Adblock Plus to help them block ads and ad trackers, thinking it was an independent company. But Adblock Plus sold them out by taking payments from ad-tech companies to let ads and trackers through.

If you’re not creeped out yet, see the documentary The Creepy Line, where researchers demonstrate how tech giants collect data and manipulate individual person’s thoughts, without the subjects even realizing they have been manipulated.

Individual persons need tools that are not made by ad tech. For example, the Electronic Frontier Foundation’s offers a browser extension called PrivacyBadger that blocks trackers. It works by sending a DNT (do not track) signal to all trackers and observing whether trackers respect it. If certain trackers do not respect the DNT signal, PrivacyBadger blocks it. Brave Browser and DuckDuckGo are other good examples of tech that was designed specifically to help consumers who couldn’t protect themselves and didn’t know who to trust.

With appropriate tools, consumers can then start the process of building trust—trust in the sites and apps that respect their privacy and provide valuable content. When users interact with the site or app, there is a transaction of value. And the transaction is between those two parties, with no hidden third-party trackers doing other shady stuff. According to Doc Searls’ transaction vs relationship framework, transactions are one-off exchanges of value, and relationships are a sequence of transactions between the same two parties over time. Consumers choose to keep interacting with sites and apps that respect their privacy preferences, thus building up trust. It takes time to build trust, but all trust can be lost in an instant, if violated. This paradigm incentivizes good behavior—that is, sites have an incentive to maintain trust and not take actions that violate it—like what AdBlock Plus did. John Wunderlich adds, “Privacy is emergent from the relationship the people enter into.” In other words, privacy is a key characteristic of a trust relationship between two parties—a symmetrical exchange of value, over time. In the current world of “surveillance capitalism”, this relationship—if it can even be called that—is asymmetrical. Companies derive all the benefit from use of personal data, at the expense of the individual person.

Data Is Not Privacy, But Data Can Be “Generally Considered to Be Private”

Now let me generalize this concept of the privacy policy of the individual beyond surveillance marketing. There are many types of data, many usage scenarios for the data, and many different people who use the data or from whom the data comes. So there are infinite combinations of type, usage scenarios and people, such that ruling a piece of data to be absolutely private at all times or absolutely not private at all times is impossible.

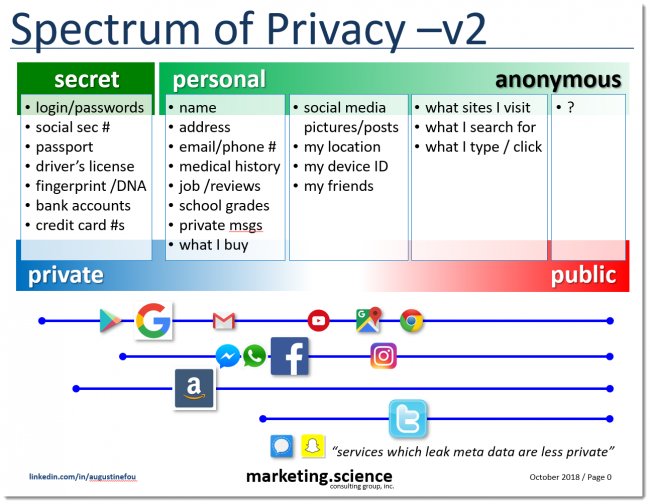

What we tend to call “privacy” today may be better thought of as “generally considered private” versus “generally considered not private”, and that refers to the data. Keep in mind, privacy pertains to the individual person, not the data. Data can be private or not private, depending on many factors. Certain types of data, like social security numbers and fingerprints, are generally considered private, but that’s not absolute and at all times. Other types of data, like email addresses and phone numbers, may be generally considered not private, but again, that’s not absolute, at all times.

These “generally considered” buckets may be illustrated by the following:

Now consider the following, as it relates to the data, not the person.

Data is private, or not, depending on usage scenario. Are pieces of data like your social security number, bank account numbers and fingerprints private? You might think, of course, your social security number is private. But what if you needed to write it down on a college application? Are your name, home address and phone number private? You might think your home address is not private, because it’s in the phone book and anyone can look it up. But, what if you didn’t want a stalker to know where you lived? What about the sites that I visit, apps that I use and what I search for online? This means that any piece of data can be private or not, depending on how it is going to be used.

Someone’s social security number is private in certain cases and not private in others. A person’s fingerprint is private in some cases and not in others, and so on. The context or usage scenario comes into play to determine whether a piece of data is private.

Data is private, or not, depending on the person. A racy selfie may be happily shared by one person on social media, but another person would be mortified if even a family photo was accidentally posted online. A millennial may freely hand their driver's license to a doorman checking age at a bar and even let them scan it into some machine without a second thought, but a more experienced person might wonder where that data goes, where is it stored, who has access to it, or what would happen if that data was stolen? So the picture in the first example and the drivers license in the second could be private or not, depending on the person.

Hamed Haddadi, adds a simple example to illustrate that while individual pieces of data in isolation can be public, “the combination of data might [need to] be private. My current location and my home address can be public by themselves. But when combined—I am at a different place from my home address—the risk might be higher; a bad guy might choose to rob my house then.” So the combination of data needs to be private, while the individual pieces may not need to be private.

Data is private, or not, depending on who has control. The social media site to which the racy selfie was posted or the maker of the license-scanning machine that stored the data might have policies on how to handle the data. But the privacy conundrum is equivalent to the 100 sites with 100 privacy policies example above. Consumers wouldn’t understand it, even if they clicked to consent to it. Sometimes after consumers agree to a privacy policy, it might be changed. What if the users don’t agree with the new terms? Would they have to leave the social network and find something else? Most consumers can’t or won’t. So they are stuck and have to accept the updated privacy policies of the services they are using.

But if we turned that around, like I said above, and made it the person’s privacy policy that sites and services have to agree to, that puts the control of the data in the hands of the individual person? That person who shared the racy selfie may change their mind in the future and want to remove it. If the social media site controlled the piece of data and the policies governing its use, it may be hard to remove and ensure that any copies are removed, because it’s no longer in the control of the person who posted it in the first place. However, if control of the data was in the hands of the individual—the origin and owner of the data—and the privacy policy was theirs and not privacy policy of someone else, all of the above would work. Companies like Iain Henderson’s JLINC.com have already started building such tech that gives individual persons a “control panel” where they can manage their own data attributes and permissions, in a standard way across the many suppliers or vendors they interact with.

Privacy Pertains to the Person; Her Data Can Be Private or Not, as Long as She Chooses

In conclusion, privacy pertains to the human person and should be thought of in terms of a human right. Data is not privacy, but data may be private or not private, depending on how it’s being used, who is using it and who has control of it. A privacy policy of the individual human person is necessary, and it's a needed replacement for the privacy policies promulgated by ad-tech companies seeking to protect their interests and maximize profits. The privacy policy of the person is like digital clothing, which signals what data they consider private. Companies that respect the person’s privacy builds relationships with the person, and the accumulation of trust over time incentivizes continued good behavior between the two parties.

This is how we build a sustainable future where human person’s privacy is respected and protected.