Pluto and Linux, the Underdog Superheroes

I'm a space nerd. That's probably not a surprise, but just how deep my nerdery goes might be. I have just about every space photo NASA has ever released. I schedule NASA.tv mission briefings on my Google Calendar as if they were specifically for me. I used to make my kids watch Shuttle launches on our TV, even if they were doing homework! (They didn't mind that so much.) Heck, growing up, I wanted to be an astronaut, but since I've worn Coke-bottle thick glasses since I was four years old, I realized I'd never be able to go to space. In fact, I'm a writer today because if I couldn't actually go to space, I wanted to write fiction about space.

I'm not a science fiction writer, although I hope someday that might change. (As a side note, if you haven't read The Martian by Andy Weir, you should do so right now. It's possibly my favorite book of all time!) I am, however, still an avid space fan. Thankfully, being a Linux user doesn't hinder me from using technology in order to augment my stargazing. In fact, Linux has an incredible set of tools available for the space nerd, and with the New Horizons probe recently passing Pluto, there's an increase in the number of people looking up at night. So first, I'm going to talk about how Linux can help you appreciate the heavens—then I plan to yammer on about Pluto for a bit. Don't worry, I'll warn you before this article jumps the shark!

The Software

There are four main astronomy packages for the Linux user. Only one of them is Linux-specific, but all work well with every distribution I've tried. There is a lot of overlap between the four programs, but each has its own unique twist as well.

Google Sky:

I want to love Google Sky—really. The idea of searching for objects in space using Google is really appealing. Unfortunately, it just never seems to work for me very well. It's perfectly possible that I've never seen how amazing it can be, but since other options exist that are Linux-native, I'm not willing to put too much effort into it.

My experience has been that Google Sky appears to have lots of graphical data, including Hubble imagery. Unfortunately, it lets you zoom in to only a few celestial objects, and in my experience, none of the planets, save Earth. I've had similar luck with Linux using Firefox and Chrome, and I even tried with OS X to similar result. If you're a Google fan and want to search the cosmos like you search for a local pizza joint, perhaps you'll have better luck than me. Check it out at https://sky.google.com.

Kstars:

Kstars is the Linux-specific program. And quite honestly, that's not entirely true. Although historically Kstars (part of the KDE suite) has been a Linux application, it does in fact run on multiple platforms. I'd be surprised if it runs as well on Windows as it does on Linux, but it seems only fair to mention the possibility.

And, although I'd like to say the Linux-specific application is my favorite, it's just not true. Kstars does have a boatload of data and more than half a million objects in its database, but the interface is more like a dynamic star map than a stargazing experience itself. That's not a bad thing, and if you're looking for research information or want to see exactly what the sky looks like from your yard, Kstars is great. To re-use my pizza metaphor from earlier though, Kstars is like my least favorite pizza. It's still pizza, and pizza is delicious!

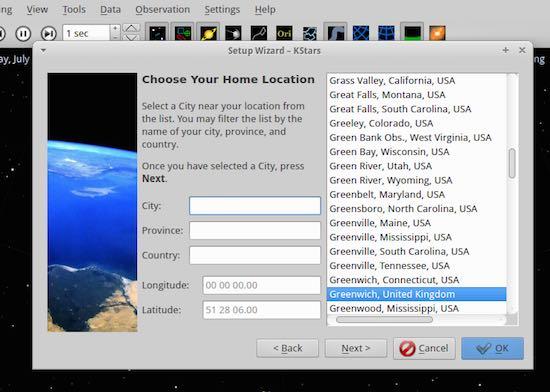

Kstars is available in most distribution's software repositories. It's

as easy as an apt-get or yum away, and there's no reason not to give it

a try. The initial setup wizard will ask you for your specific location

(Figure 1), and unless you live in a big city, it likely won't be able

to find you. In order to get an accurate view of your night sky, you'll

need to know your precise latitude and longitude coordinates. (Google

should be able to help you find that information.)

Figure 1. Kstars is a powerful program with loads of data and the ability to import even more.

Celestia:

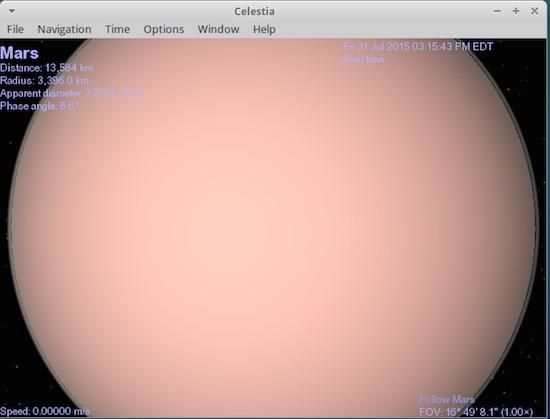

My favorite feature of Celestia (a GTK program) is the ability to "fly" to other planets (Figure 2). Perhaps it's my lingering dreams of being an astronaut, but there's something about flying through the cosmos to a distant planet or galaxy that really appeals to me. Celestia also does time shifting, which allows you to see what the stars and planets will look like, or did look like, on any given day. Although it's not exactly powerful enough to predict a collision with a Near Earth Asteroid, it does make planning for a future evening of stargazing much more fun. Traveling to a Dark Skies park with a Dobsonian light bucket only to discover Saturn has dipped below the horizon can make for a horrible evening. Time shifting is incredibly useful. You can get Celestia for your Linux (or other) computer in the software repository or at https://www.shatters.net/celestia.

Figure 2. A still photo can't do the "flying" feature justice.

Stellarium:

I won't try to hide it, Stellarium is my favorite piece of astronomy software. Celestia wins the wow factor with its "cruise through space" feature, but Stellarium wins for me in every other way—except when it comes to quitting the program. Honestly, I couldn't figure it out for a long time. There's no quit button from what I can tell, and I just couldn't figure out how to exit the program (which starts in full-screen mode, making quitting even more challenging). Let me save you some time: Ctrl-Q. You're welcome.

Some of my favorite features include:

-

Graphical Horizon: not only does Stellarium give you the view of the sky from your latitude and longitude coordinates, but it also shows you what to expect on the horizon. This includes what it might look like with trees, buildings and so on (Figure 3). Although it's a generic trees/buildings skyline, it does help approximate what you can expect to see. If Jupiter is just over the horizon, you might not see it if there are houses in the way. It's not perfect, but it's a great visualization tool. That said, I think it would be amazing to integrate a feed from Google Street View to see what the actual skyline might look like, but I'm sure there are practical reasons that hasn't been implemented.

-

Night Mode: the other programs I mention in this article might have a night mode, but I've never seen the option. With Stellarium, a simple click into night mode will change all the graphics to a red color. If you're a stargazer, you probably know that red lights don't ruin night vision like other colors of light. That means you can take your laptop out with you and use it in the field to identify objects without ruining your adjusted night vision.

-

Interplanetary Visitation: okay, I made that term up, but as a wannabe science fiction writer, it's a pretty significant feature. Have you ever wondered what the stars look like from Mars? With Stellarium, you can adjust your point of reference and see the universe from other places in the universe. I can't wait for the data to be updated enough to stand on Pluto and look at Charon with high-resolution images from New Horizons.

-

Time Shifting: this isn't unique to Stellarium, but it's a feature I really like. Not only can you travel to a different time in the past or future, but you actually can "fast-forward" time to see the changes that will occur in a pseudo-video of events. This helps young kids see the stars move when in real life they appear to be static. (Okay, the stars aren't actually moving around, it's us that is moving, but that's part of the discussion to have with your kids. More learning!)

Figure 3. The horizon feature is incredible and helps identify where you're looking.

Stellarium is available in most distributions, or you can head over to https://stellarium.org and download the version for your operating system. Some nights, especially in the winter, I like to play with Stellarium and stare at the night sky from the confines of my cozy house. A large monitor and a dark room can make Stellarium almost as good as the real thing. Almost.

Mobile Magic

As much as I like computer software for finding and planning stargazing sessions, they're honestly not my go-to way to technologize the cosmos. For that, I tend to whip out my cell phone and point it at the sky. No, I don't try to call E.T.; rather I employ apps like Star Walk (my favorite) to use "augmented reality", which is the coolest thing since telescopes.

With Star Walk (or Sky Map, or Star Chart), you simply hold your phone toward the sky, and using GPS coordinates, motion sensors and digital compass, the app shows you an overlay of what you're pointing at. Want to know what that super-bright star is on the horizon? (It's probably Venus.) Just point your phone at it, and you'll see a nice clear label. Not sure if you're seeing a cluster of stars in the distance or just a smudge on your binoculars? Pinch out to zoom in and look (Figure 4). Truly, smartphones have changed the way nerds like me share excitement about stars and such with others. I've personally never seen Pluto in a telescope, but I've pointed my phone at the sky knowing I'm looking in the right direction. It's a little like having a GPS device for stargazing. It's incredibly awesome.

Figure 4. Smartphones have changed the way we stargaze.

You can find Star Walk and the other Android apps I mentioned in the Google Play store. I could give you URLs, but really, I've come to the conclusion that it's easier just to search by name. Star Walk isn't free, but it's only a few dollars and well worth the price of admission. And with that, I must warn you, I'm going to talk about our formerly-a-planet friend, Pluto.

Shawn's Excitement, and Soapbox

Almost exactly in time for my 40th birthday (literally, three days before), the New Horizons probe zoomed past Pluto and its moons at more than 50,000km/hr. There was no way for it to slow down, but the flyby was the goal of the mission, and it succeeded! In a matter of a week, we learned more about Pluto than we've ever known in the history of mankind—and that information wasn't what we were expecting at all.

Pluto is so small and cold, we expected to see an ancient, cratered, frozen rock. Instead, we discovered a geologically active world with young mountain ranges and atmospheric attributes never imagined possible. Although most of the world looked at the charming heart-shaped area on the photo (Figure 5), scientists were wondering where the craters were and how on earth mountains formed. See, a lack of craters means the surface is changing and reforming, covering up impact craters. And the mountains mean there has been some sort of geological action like we see on Earth.

Figure 5. I <3 you too, Pluto!

We have no idea why—and that's awesome. Jupiter's moon Io is geologically active, but we understand why. With Jupiter's gravity squeezing it, Io has no choice but to spew lava out of volcanoes. If you've ever bent a metal coat hanger back and forth, you know firsthand how friction can cause heat. Jupiter's squeezing literally causes enough friction on Io to make it geologically active. Our own planet has an active, molten core that causes our geologic activity.

Pluto shouldn't have either. Charon isn't large enough to squeeze Pluto, and the dwarf planet is so small it should have cooled off long ago. So why is Pluto geologically active? We don't know! Yay for science!

I won't get too high on my soapbox about how sad I am over the budget slashing our space program has received during the past 50 years. Space exploration is a passion of mine, and until it's a passion for the rest of the world, its budgetary importance will remain low. Although I won't urge you one way or another politically, I will urge you to introduce your spouses, kids, nephews, nieces and grandkids to the cosmos. You can use Linux to make it technological and relevant, and with smartphones, you even can make it relevant to teenagers!

And really, you should read that Andy Weir book. It's incredible!