An Immodest Proposal for the Music Industry

How music listeners can fill the industry's "value gap".

From the 1940s to the 1960s, countless millions of people would put a dime in a jukebox to have a single piece of music played for them, one time. If they wanted to hear it again, or to play another song, they'd put in another dime.

In today's music business, companies such as Spotify, Apple and Pandora pay fractions of a penny to stream songs to listeners. While this is a big business that continues to become bigger, it fails to cover what the music industry calls a "value gap".

They have an idea for filling that gap. So do I. The difference is that mine can make them more money, with a strong hint from the old jukebox business.

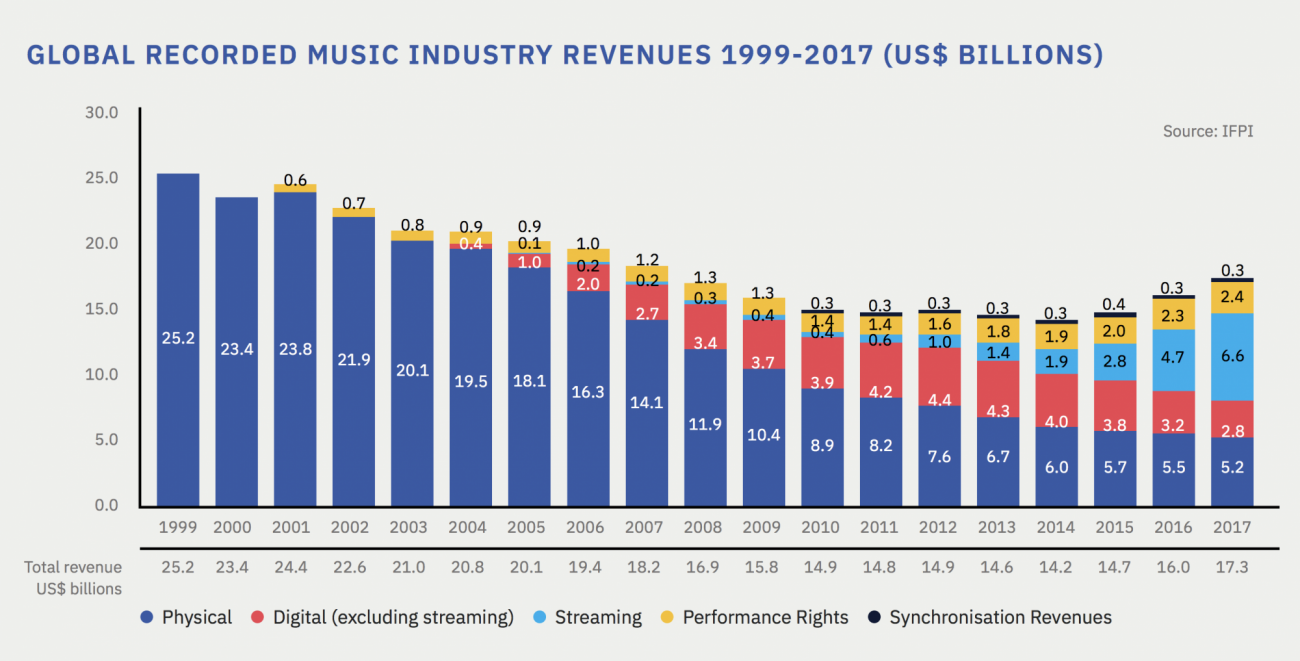

For background, let's start with this graph from the IFPI's Global Music Report 2018:

Figure 1. Global Music Report 2018

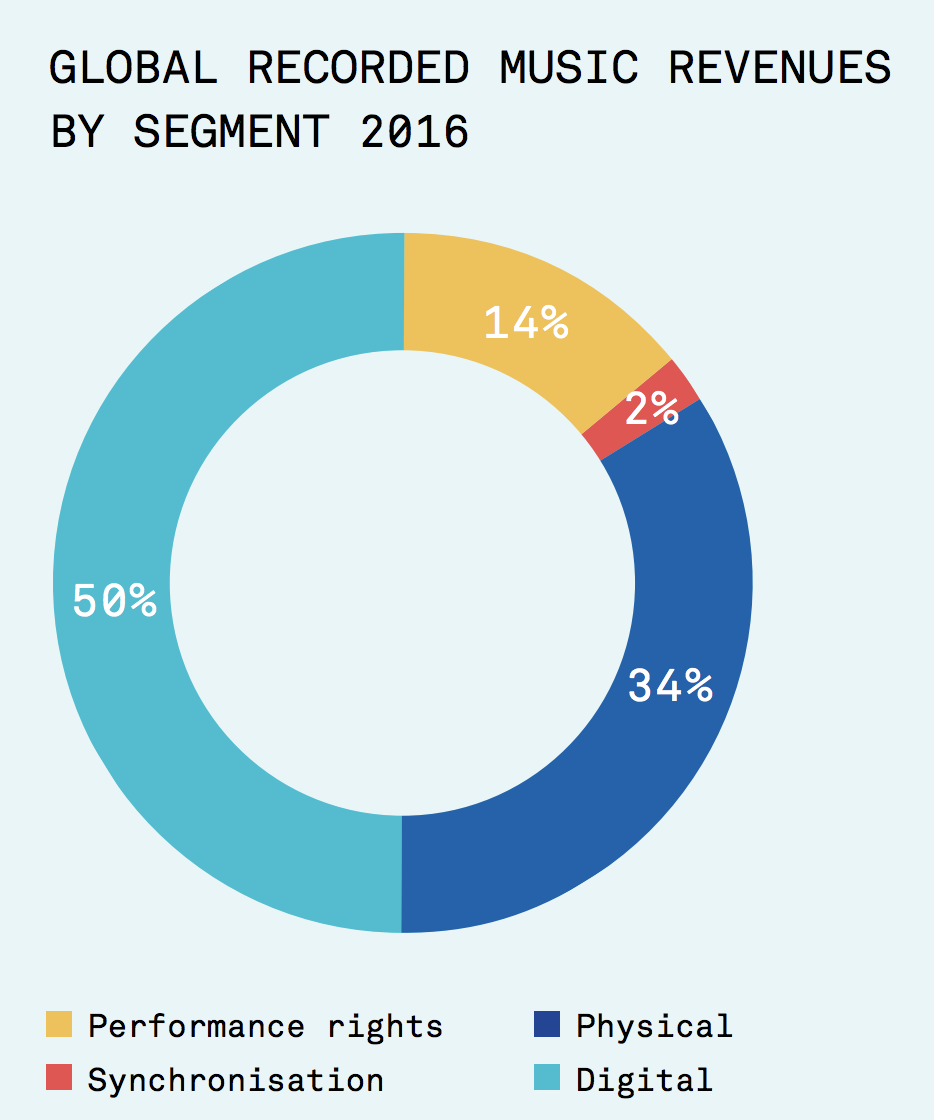

You can see why IFPI no longer gives its full name: International Federation of the Phonographic Industry. That phonographic stuff is what they now call "physical". And you see where that's going (or mostly gone). You also can see that what once threatened the industry—"digital"—now accounts for most of its rebound (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Global Recorded Music Revenues by Segment (2016)

The graphic shown in Figure 2 is also a call-out from the first. Beside it is this text: "Before seeing a return to growth in 2015, the global recording industry lost nearly 40% in revenues from 1999 to 2014."

Later, the report says:

However, significant challenges need to be overcome if the industry is going to move to sustainable growth. The whole music sector has united in its effort to fix the fundamental flaw in today's music market, known as the "value gap", where fair revenues are not being returned to those who are creating and investing in music.

They want to solve this by lobbying: "The value gap is now the industry's single highest legislative priority as it seeks to create a level playing field for the digital market and secure the future of the industry." This has worked before. Revenues from streaming and performance rights owe a lot to royalty and copyright rates and regulations guided by the industry. (In the early 2000s, I covered this like a rug in Linux Journal. See here.)

But, there's another way to fill that gap: on the listening side. You can see a hint in that direction from growth in live performance revenues. According to Statista, live music industry revenue:

...will grow from 9.28 billion U.S. dollars in 2015 to 11.99 billion in 2021. Of the revenue generated in 2016, over two billion U.S. dollars was generated in sponsorship, and a further 7.4 billion U.S. dollars came in ticket sales. The industry is expected to grow further in the coming years as the compound annual growth rate for live music ticket sales is estimated at 5.23 percent between 2015 and 2020.

According to a July 16, 2018, post in Pollstar:

There is perhaps no better indicator of a robust 2018 live market than Pollstar's Mid-Year Top 50 Worldwide Tours chart. This year's survey saw a 12% jump in total gross from last year's $1.97 billion to a record-setting $2.21 billion—a $240 million increase. It's the chart's biggest rise since 2015–16...

Concert promoters also are raising prices. Says a July 9, 2018, report by ABC News:

The average price of a concert ticket during the first six months of the year was $46.69—4.2 percent higher than the average cost of a ticket for the same period last year, according to the latest figures from music industry magazine Pollstar. That price is almost 7 percent higher than the average for all of 2000, and an even more startling 43 percent increase over what concert tickets cost just three years ago, according to Pollstar.

That same report says sales are going down: a market signal that the prices are too high. But hey, people are clearly willing to pay a lot for live music and a participatory experience. This is an important clue.

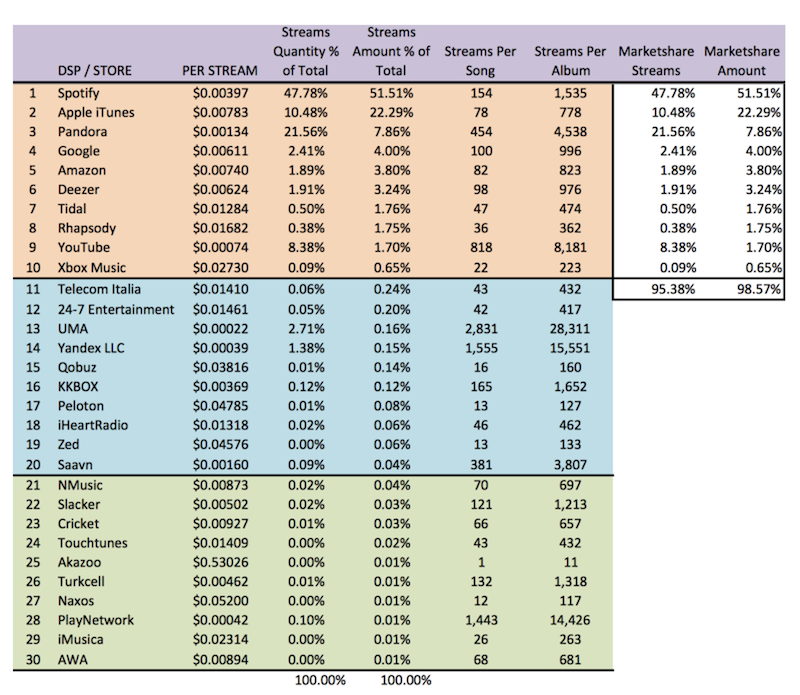

Participation requires good signaling from both sides of the marketplace. So let's look at the demand side, shown in Figure 3, starting with what the streaming services pay to play us a tune.

Figure 3. What the Streaming Services Pay to Play a Tune (from Trichordist

To make that clearer, the top three streamers pay between 13.4% (Pandora) and 78.3% of a penny ($.01) to play you a song.

SiriusXM pays (it says here) "19.1% of the price of all audio packages which include music channels". That means the $209.76 I paid last August for my SiriusXM subscription sent $40.01 to the rights-holders of all the music played on all the SiriusXM channels for my account over the following year, whether I listened to any music or not. (And mostly I listen to non-music channels.)

YouTube is another special case. The 2018 IFPI report says, "From publicly available data, IFPI estimates that Spotify paid record companies US$20 per user in 2015, the last year of available data. By contrast, it is estimated that YouTube returned less than US$1 for each music user." That's a big part of the "value gap".

Some of those rates are negotiated, others are set by regulation, and most are informed—one way or another—by both.

In no case, however, does the music listener pay for digital music on the jukebox model: with cash on a per-listen, per-song basis. (Note that a dime in 1960 was more than 100x what a streamer pays for the right to play a song for somebody.)

So that's my proposal: create an easy way for any of us to pay what we want for the music we hear. This will give music lovers their own way to close the value gap—and then some.

As it happens, an easy way to do this was proposed by ProjectVRM (which I run at Harvard's Berkman Klein Center) way back in 2009. It's called EmanciPay, and here is how it is described on the project wiki:

Simply put, EmanciPay makes it easy for anybody to pay (or offer to pay) —

- as much as they like

- however they like

for whatever they like- on their own terms

— or at least to start with that full set of options, and to work out differences with sellers easily and with minimal friction.

EmanciPay turns consumers (aka users) into customers by giving them a pricing gun (something which in the past only sellers used) and their own means to make offers, to pay outright, and to escrow the intention to pay when price and other requirements are met. Payments themselves can also be escrowed.

In slightly more technical terms, EmanciPay is a payment framework for customers operating with full agency in the open marketplace. It operates on open protocols and standards, so it can be used by any buyer, seller or intermediary...

So, as currently planned, EmanciPay would —

- Provide a single and easy way that consumers of "content" can become customers of it. In the current system—which isn't one—every artist, every musical group, every public radio and TV station, has his, her or its own way of taking in contributions from those who appreciate the work. This can be arduous and time-consuming for everybody involved. (Imagine trying to pay separately every musical artist you like, for all your enjoyment of each artist's work.) What EmanciPay proposes, however, is not a replacement for existing systems, but a new system that can supplement existing fund-raising systems—one that can soak up much of today's MLOTT: Money Left On The Table.

- Provide ways for individuals to look back through their media usage histories, inform themselves about what they have been enjoying, and to determine how much it is worth to them. The Copyright Arbitration Royalty Panel (CARP), and later the Copyright Royalty Board (CRB), both came up with "rates and terms that would have been negotiated in the marketplace between a willing buyer and a willing seller"—language that first appeared in the 1995 Digital Performance Royalty Act (DPRA), and was tweaked in 1998 by the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), under which both the CARP and the CRB operated. The rates they came up with peaked at $.0001 per "performance" (a song or recording), per listener. EmanciPay creates the "willing buyer" that the DPRA thought wouldn't exist.

- Stigmatize non-payment for worthwhile media goods. This is where "social" will finally come to be something more than yet another tech buzzmodifier.

All these require micro-accounting, not micro-payments. In fact micro-accounting can inform ordinary payments that can be made in clever new ways that should satisfy everybody with an interest in seeing artists compensated fairly for their work. An individual listener, for example, can say "I want to pay one cent for every song I hear on the radio", and "I'll send SoundExchange a lump sum of all the pennies I wish to pay for songs I hear over the course of a year, along with an accounting of what artists and songs I've listened to"—and leave dispersal of those totaled pennies up to the kind of agency that likes, and can be trusted, to do that kind of thing.

Similar systems can also be put in place for readers of newspapers, blogs and other journals. What's important is that the control is in the hands of the individual, and that the accounting and dispersal systems work the same way for everybody.

I also proposed this earlier in "EmanciPay: A Content Monetization Plan for Newspapers", and later in "An Easy Way to Pay for Journalism, Music and Everything Else We Like". In the first of those, I wrote:

Think of EmanciPay as a way to unburden sellers of the need to keep trying to control markets that are beyond their control anyway. Think of it as a way that "free market" can mean more than "your choice of captor". Think of it as a way that "customer relationships" can be worthy of the label because both sides are carrying their ends of the relationship burden—rather than the sellers' side carrying the whole thing.

It'll be fun to start doing that in the music industry.

A number of developments make the opportunity ripe now:

- The music industry is far less scattered and conflicted about its nature (digital now) and future (gotta make up that value gap) than it ever was in the past.

- Former enemies can be friends. For example, open source and the music industry have both won, and many aligned incentives can be found between them.

- Music listeners are clearly willing to pay value for value. We just need to create the ways. And it shouldn't be hard. (Especially for Linux Journal readers.)

- The jukebox and live performance examples both suggest that people shouldn't have a problem saying "I'll be glad to set up a way to pay one cent every time I hear music I like."

- Apple just bought Shazam, which is a way to identify music people hear. That kind of functionality can be brought into standard ways people can pay for music they passively hear (for example, in a restaurant or at parties) and like.

- We've long needed a standards-based approach to tipping artists—or anybody—with maximal ease and minimal friction. One can be crafted out of work on EmanciPay.

While most of my usual appeals in Linux Journal are to the hackers among us, this appeal is mostly to my friends (old and new) in the music industry. They have the connections, the talent, the legal smarts, the money and the motivation required to make this thing work.

So let's bring the people who love music into the marketplace as willing buyers. And let's do it by standardizing simple ways people can, by routine or impulse, be real customers of music and not just passive consumers (or worse, what the industry used to call pirates). Let's also create new ways, beyond payments alone, that artists and music lovers can signal each other, and have all kinds of creative fun.

The time is right. Let's not let the opportunity pass.

Note: Jukebox image by Davide Cavalli [CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons.