Help Us Cure Online Publishing of Its Addiction to Personal Data

Since the turn of the millennium, online publishing has turned into a vampire, sucking the blood of readers' personal data to feed the appetites of adtech: tracking-based advertising. Resisting that temptation nearly killed us. But now that we're alive, still human and stronger than ever, we want to lead the way toward curing the rest of online publishing from the curse of personal-data vampirism. And we have a plan. Read on.

This is the first issue of the reborn Linux Journal, and my first as Editor in Chief. This is also our first issue to contain no advertising.

We cut out advertising because the whole online publishing industry has become cursed by the tracking-based advertising vampire called adtech. Unless you wear tracking protection, nearly every ad-funded publication you visit sinks its teeth into the data jugulars of your browsers and apps to feed adtech's boundless thirst for knowing more about you.

Both online publishing and advertising have been possessed by adtech for so long, they can barely imagine how to break free and sober up—even though they know adtech's addiction to human data blood is killing them while harming everybody else as well. They even have their own twelve-step program.

We believe the only cure is code that gives publishers ways to do exactly what readers want, which is not to bare their necks to adtech's fangs every time they visit a website—and at the same time allow sponsors to do advertising the old fashioned way: without tracking.

We're doing that by reversing the way terms of use work. Instead of readers always agreeing to publishers' terms, publishers will agree to readers' terms. The first of these will say something like this:

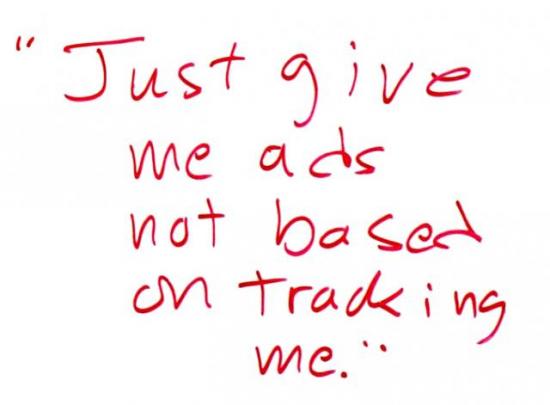

That appeared on a whiteboard one day when we were talking about terms readers proffer to publishers, if that option was available. Customer Commons calls these Personal Data Usage Terms, or #PDUTs. (Earlier work at ProjectVRM called these EmanciTerms. The idea behind Customer Commons (which I co-founded, and on the board of which I serve) is to do for personal terms what Creative Commons does for personal copyright. The first of those is #P2B1(beta), aka #NoStalking.

Publishers and advertisers can both accept that term, because it's exactly what advertising has always been in the offline world, as well as in the too-few parts of the online world where advertising sponsors publishers while not getting personal with readers.

By agreeing to #NoStalking, publishers will also have a stake it can drive into the heart of adtech.

At Linux Journal, we have set a deadline for standing up a working proof of concept: 25 May 2018. That's the day regulatory code from the EU called the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) takes effect. The GDPR is aimed at the same data vampires, and its fines for violations run up to 4% of a company's revenues in the prior fiscal year. It's a very big deal, and it has opened the minds of publishers and advertisers to anything that moves them toward GDPR compliance.

With the GDPR putting fear in the hearts of publishers and advertisers everywhere, #DoNotByte may succeed where DoNotTrack (which the W3C has now ironically relabeled Tracking Preference Expression) failed.

In addition to helping Customer Commons with #NoStalking, here's what we have in the works so far:

- Our steadily improving Drupal website.

- A protocol from JLINCLabs by which readers can proffer terms, plus a way to record agreements that leaves an audit trail for both sides.

- Code from Aloodo that helps sites discover how many visitors are protected from tracking, while also warning visitors if they aren't—and telling them how to get protected. Here's Aloodo's Github site. (Aloodo is a project of Don Marti, who precedes me as Editor in Chief of Linux Journal. He now works for Mozilla.)

We need help with all of those, plus whatever additional code and labor anyone brings to the table.

Before going more deeply into that, let's unpack the difference between real advertising and adtech, and how mistaking the latter for the former is one of the ways adtech tricked publishing into letting adtech into its bedroom at night:

- Real advertising isn't personal, doesn't want to be (and, in the offline world, can't be), while adtech wants to get personal. To do that, adtech spies on people and violates their privacy as a matter of course, and rationalizes it completely, with costs that include becoming a big fat target for bad actors.

- Real advertising's provenance is obvious, while adtech messages could be coming from any one of hundreds (or even thousands) of different intermediaries, all of which amount to a gigantic four-dimensional shell game no one entity fully comprehends. Those entities include SSPs, DSPs, AMPs, DMPs, RTBs, data suppliers, retargeters, tag managers, analytics specialists, yield optimizers, location tech providers...the list goes on. And on. Nobody involved—not you, not the publisher, not the advertiser, not even the third party (or parties) that route an ad to your eyeballs—can tell you exactly why that ad is there, except to say they're sure some form of intermediary AI decided it is "relevant" to you, based on whatever data about you, gathered by spyware, reveals about you. Refresh the page and some other ad of equally unclear provenance will appear.

- Real advertising has no fraud or malware (because it can't—it's too simple and direct for that), while adtech is full of both.

- Real advertising supports journalism and other worthy purposes, while adtech supports "content production"—no matter what that "content" might be. By rewarding content production of all kinds, adtech gives fake news a business model. After all, fake news is "content" too, and it's a lot easier to produce than the real thing. That's why real journalism is drowning under a flood of it. Kill adtech and you kill the economic motivation for most fake news. (Political motivations remain, but are made far more obvious.)

- Real advertising sponsors media, while adtech undermines the brand value of both media and advertisers by chasing eyeballs to wherever they show up. For example, adtech might shoot an Economist reader's eyeballs with a Range Rover ad at some clickbait farm. Adtech does that because it values eyeballs more than the media they visit. And most adtech is programmed to cheap out on where it is placed, and to maximize repeat exposures wherever it can continue shooting the same eyeballs.

In the offline publishing world, it's easy to tell the difference between real advertising and adtech, because there isn't any adtech in the offline world, unless we count direct response marketing, better known as junk mail, which adtech actually is.

In the online publishing world, real advertising and adtech look the same, except for ads that feature this symbol:

![]()

Only not so big. You'll only see it as a 16x16 pixel marker in the corner of an ad, so it actually looks super small.

Click on that tiny thing and you'll be sent to an "AdChoices" page explaining how this ad is "personalized", "relevant", "interest-based" or otherwise aimed by personal data sucked from your digital neck, both in real time and after you've been tracked by microbes adtech has inserted into your app or browser to monitor what you do.

Text on that same page also claims to "give you control" over the ads you see, through a system run by Google, Adobe, Evidon, TrustE, Ghostery or some other company that doesn't share your opt-outs with the others, or give you any record of the "choices" you've made. In other words, together they all expose what a giant exercise in misdirection the whole thing is. Because unless you protect yourself from tracking, you're being followed by adtech for future ads aimed at your eyeballs using source data sucked from your digital neck.

By now you're probably wondering how adtech has come to displace real advertising online. As I put it in "Separating Advertising's Wheat and Chaff", "Madison Avenue fell asleep, direct response marketing ate its brain, and it woke up as an alien replica of itself." That happened because Madison Avenue, like the rest of big business, developed a big appetite for "big data", starting in the late 2000s. (I unpack this history in my EOF column in the November 2015 issue of Linux Journal.)

Madison Avenue also forgot what brands are and how they actually work. After a decade-long trial by a jury that included approximately everybody on Earth with an internet connection, the verdict is in: after a $trillion or more has been spent on adtech, no new brand has been created by adtech; nor has the reputation of an existing brand been enhanced by adtech. Instead adtech does damage to a brand every time it places that brand's ad next to fake news or on a crappy publisher's website.

In "Linux vs. Bullshit", which ran in the September 2013 Linux Journal, I pointed to a page that still stands as a crowning example of how much of a vampire the adtech industry and its suppliers had already become: IBM and Aberdeen's "The Big Datastillery: Strategies to Accelerate the Return on Digital Data".

The "datastillery" is a giant vat, like a whiskey distillery might have. Going into the top are pipes of data labeled "clickstream data", "customer sentiment", "email metrics", "CRM" (customer relationship management), "PPC" (pay per click), "ad impressions", "transactional data" and "campaign metrics". All that data is personal, and little if any of it has been gathered with the knowledge or permission of the persons it concerns.

At the bottom of the vat, distilled marketing goop gets spigoted into beakers rolling by on a conveyor belt through pipes labeled "customer interaction optimization" and "marketing optimization."

Now get this: those beakers are human beings.

Farther down the conveyor belt, exhaust from goop metabolized in these human beakers is farted upward into an open funnel at the bottom end of the "campaign metrics" pipe, through which it flows back to the top and is poured back into the vat.

This "datastillery" is an MRI of the vampire's digestive system: a mirror in which IBM's and Aberdeen's reflection fails to appear because their humanity is gone.

Thus, it should be no wonder ad blocking is now the largest boycott in human history. Here's how large:

- PageFair's 2017 Adblock Report says at least 615 million devices were already blocking ads by then. That number is larger than the human population of North America.

- GlobalWebIndex says 37% of all mobile users worldwide were blocking ads by January 2016, and another 42% would like to. With more than 4.6 billion mobile phone users in the world, that means 1.7 billion people were blocking ads already—a sum exceeding the population of the Western Hemisphere.

Naturally, the adtech business and its dependent publishers cannot imagine any form of GDPR compliance other than continuing to suck its victims dry while adding fresh new inconveniences along those victims' path to adtech's fangs—and then blaming the GDPR for delaying things.

A perfect example of this non-thinking is a recent Business Insider piece that says "Europe's new privacy laws are going to make the web virtually unsurfable" because the GDPR and ePrivacy (the next legal shoe to drop in the EU) "will require tech companies to get consent from any user for any information they gather on you and for every cookie they drop, each time they use them", thus turning the web "into an endless mass of click-to-consent forms".

Speaking of endless, the same piece says, "News sites—like Business Insider—typically allow a dozen or more cookies to be 'dropped' into the web browser of any user who visits." That means a future visitor to Business Insider will need to click "agree" before each of those dozen or more cookies get injected into the visitor's browser.

After reading that, I decided to see how many cookies Business Insider actually dropped in my Chrome browser when that story loaded, or at least tried to. Here's what Baycloud Bouncer reported:

That's ten-dozen cookies.

This is in addition to the almost complete un-usability Business Insider achieves with adtech already. For example:

- On Chrome, Business Insider's third-party adtech partners take forever to load their cookies and auction my "interest" (over a 320MBp/s connection), while populating the space around the story with ads—just before a subscription-pitch paywall slams down on top of the whole page like a giant metal paving slab dropped from a crane, making it unreadable on purpose and pitching me to give them money before they lift the slab.

- The same thing happens with Firefox, Brave and Opera, although not at the same rate, in the same order or with the same ads. All drop the same paywall though. It's hard to imagine a more subscriber-hostile sales pitch.

- Yet, I could still read the piece by looking it up in a search engine. It may also be elsewhere, but the copy I find is on MSN. There the piece is also surrounded by ads, which arrive along with cookies dropped in my browser by only 113 third-party domains. Mercifully, no subscription paywall slams down on the page.

So clearly the adtech business and their publishing partners are neither interested in fixing this thing, nor competent to do it.

But one small publisher can start. That's us. We're stepping up.

Here's how: by reversing the compliance process. By that I mean we are going to agree to our readers' terms of data use, rather than vice versa. Those terms will live at Customer Commons, which is modeled on Creative Commons. Look for Customer Commons to do for personal terms what Creative Commons did for personal copyright licenses.

It's not a coincidence that both came out of Harvard's Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society. The father of Creative Commons is law professor Lawrence Lessig, and the father of Customer Commons is me. In the great tradition of open source, I borrowed as much as I could from Larry and friends.

For example, Customer Commons' terms will come in three forms of code (which I illustrate with the same graphic Creative Commons uses):

Legal Code is being baked by Customer Commons' counsel: Harvard Law School students and teachers working for the Cyberlaw Clinic at the Berkman Klein Center.

Human Readable text will say something like "Just show me ads not based on tracking me." That's the one we're dubbing #DoNotByte.

For Machine Readable code, we now have a working project at the IEEE: 7012 - Standard for Machine Readable Personal Privacy Terms. There it says:

The purpose of the standard is to provide individuals with means to proffer their own terms respecting personal privacy, in ways that can be read, acknowledged and agreed to by machines operated by others in the networked world. In a more formal sense, the purpose of the standard is to enable individuals to operate as first parties in agreements with others—mostly companies—operating as second parties.

That's in addition to the protocol and a way to record agreements that JLINCLabs will provide.

And we're wide open to help in all those areas.

Here's what agreeing to readers' terms does for publishers:

- Helps with GDPR compliance, by recording the publisher's agreement with the reader not to track them.

- Puts publishers back on a healthy diet of real (tracking-free) advertising. This should be easy to do because that's what all of advertising was before publishers, advertisers and intermediaries turned into vampires.

- Restores publishers' status as good media for advertisers to sponsor, and on which to reach high-value readers.

- Models for the world a complete reversal of the "click to agree" process. This way we can start to give readers scale across many sites and services.

- Pioneers a whole new model for compliance, where sites and services comply with what people want, rather than the reverse (which we've had since industry won the Industrial Revolution).

- Raises the value of tracking protection for everybody. In the words of Don Marti, "publishers can say, 'We can show your brand to readers who choose not to be tracked.'" He adds, "If you're selling VPN services, or organic ale, the subset of people who are your most valuable prospective customers are also the early adopters for tracking protection and ad blocking."

But mostly we get to set an example that publishing and advertising both desperately need. It will also change the world for the better.

You know, like Linux did for operating systems.