Everything You Need to Know about the Cloud and Cloud Computing, Part I

An in-depth breakdown of the technologies involved in making up the cloud and a survey of cloud-service providers.

The cloud has become synonymous with all things data storage. It additionally equates to the many web-centric services accessing that same back-end data storage. But the term also has evolved to mean so much more.

Cloud computing provides more simplified access to server, storage, database and application resources, with users provisioning and using the minimum set of requirements they see fit to host their application needs. In the past decade alone, the paradigm shift toward a wider and more accessible network has forced both hardware vendors and service providers to rethink their strategies and cater to a new model of storing information and serving application resources. As time continues to pass, more individuals and businesses are connecting themselves to this greater world of computing.

What Is the Cloud?

Far too often, the idea of the "cloud" is confused with the general internet. Although it's true that various components making up the cloud can be accessible via the internet, they are not one and the same. In its most general terms, cloud computing enables companies, service providers and individuals to provision the appropriate amount of computing resources dynamically (compute nodes, block or object storage and so on) for their needs. These application services are accessed over a network—and not necessarily a public network. Three distinct types of cloud deployments exist: public, private and a hybrid of both.

The public cloud differentiates itself from the private cloud in that the private cloud typically is deployed in the data center and under the proprietary network using its cloud computing technologies—that is, it is developed for and maintained by the organization it serves. Resources for a private cloud deployment are acquired via normal hardware purchasing means and through traditional hardware sales channels. This is not the case for the public cloud. Resources for the public cloud are provisioned dynamically to its user as requested and may be offered under a pay-per-usage model or for free.

Some of the world's leading public cloud offering platforms include:

- Amazon Web Services (AWS)

- Microsoft Azure

- Google Cloud Platform

- IBM Cloud (formerly SoftLayer)

As the name implies, the hybrid model allows for seamless access and transitioning between both public and private deployments, all managed under a single framework.

For those who prefer either to host their workload internally or partially on the public cloud—sometimes motivated by security, data sovereignty or compliance—private and hybrid cloud offerings continue to provide the same amount of service but all within your control.

Using cloud services enables you to achieve the following:

- Enhance business agility with easy access and simplified deployment of operating systems/applications and management of allocated resources.

- Reduce capital expenses and optimize budgets by reducing the need to worry about the hardware and overall data center/networking infrastructure.

- Transform how you deliver services and manage your resources that flexibly scale to meet your constantly evolving requirements.

- Improve operations and efficiency without worrying about hardware, cooling or administration costs—you simply pay for what you need and use (this applies to the public option).

Adopting a cloud model enables developers access to the latest and greatest tools and services needed to build and deploy applications on an instantly available infrastructure. Faster development cycles mean that companies are under pressure to compete at a faster velocity or face being disrupted in the market. This new speed of business coupled with the mindset of "on-demand" and "everything-as-a-service" extends beyond application developers into finance, human resources and even sales.

The Top Players in the Industry

For this Deep Dive series, I focus more on the public cloud service providers and their offerings with example deployments using Amazon's AWS. Why am I focusing on the public cloud? Well, for most readers, it may appear to be the more attractive option. Why is that? Unlike private cloud and on-premises data-center deployments, public cloud consumption is designed to relieve maintainers of the burden to invest and continuously update their computing hardware and networking infrastructures. The reality is this: hardware gets old and it gets old relatively quickly.

Public clouds are designed to scale, theoretically, without limit. As you need to provision more resources, the service providers are well equipped to meet those requirements. The point here is that you never will consume all of the capacity of a public cloud.

The idea is to reduce (and potentially remove) capital expenditure (capex) significantly and focus more on the now-reduced operational expenditure (opex). This model allows for a company to reduce its IT staffing and computing hardware/software costs. Instead of investing heavily upfront, companies are instead subscribing to the infrastructure and services they need. Remember, it's a pay-as-you-go model.

Note: service providers are not limited to the ones mentioned here. This listing consists of the providers with the largest market share.

Amazon

First launched in 2006, Amazon Web Services (AWS) offers a suite of on-demand cloud computing, storage and networking resources, and data storage. Today, AWS additionally provides an extensive list of services that focus on compute, storage, networking, database, analytics, developer tools and many more. The most well known of these services are the Amazon Elastic Compute Cloud (EC2) and the Amazon Simple Storage Service (S3). (I cover those offerings and more in Part II of this series.)

Amazon stands at the forefront of the public cloud with the largest market share of users—by a substantial amount at that. Being one of the very first to invest in the cloud, Amazon has been able to adapt, redefine and even set the trends of the industry.

Microsoft

Released to the general public in 2010, Microsoft Azure redefined computing to existing Microsoft ecosystems and beyond. Yes, this includes Linux. Much like AWS, Azure provides customers with a large offering of attractive cloud products that cover compute, storage, databases and more. Microsoft has invested big in the cloud, and it definitely shows. It's no surprise that Microsoft currently is the second-largest service provider, quickly approaching Amazon's market share.

Google's entry into this market was an evolving one. Embracing the cloud and cloud-style computing early on, Google essentially would make available internally implemented frameworks to the wider public as it saw fit. It wasn't until around 2010 with the introduction of Google Cloud Storage that the foundations of the Google Cloud Platform were laid for the general public and future cloud offerings. Today, Google remains a very strong competitor.

IBM

IBM announced its cloud ambitions in 2012. The vision (and name) has evolved since that announcement, but the end result is the same: compute, storage and so on, but this time, with an emphasis on security, hybrid deployments and a connection to an Artificial Intelligence (AI) back end via the infamous Watson framework.

Architectural Overview

The whole notion of cloud computing has evolved since its conception. The technology organically grew to meet new consumer needs and workloads with even newer features and functionality (I focus on this evolution in Part II of this series). It would be extremely unfair and unrealistic of me to say that the following description covers all details of your standard cloud-focused data centers, so instead, I'm making it somewhat general.

Regions and Zones

In the case of Amazon, AWS places its data centers across 33 availability zones within 12 regions worldwide. A region is a separate geographic location. Each availability zone has one or more data centers. Each data center is equipped with 50,000–80,000 servers, and each data center is configured with redundant power for stability, networking and connectivity. Microsoft Azure runs across 36 global regions, each region consisting of a single data center serving that particular region. IBM Cloud operates from at least 33 single data-center regions worldwide, each consisting of thousands (if not tens of thousands) of servers.

As a user, you are able to place a virtual instance or resource in multiple locations and across multiple zones. If those resources need to be replicated across multiple regions, you need to ensure that you adjust the resource to do exactly that.

This approach allows both users and corporations to leverage the cloud provider's high availability. For instance, if I am company foo, providing service bar and, in turn, rely on AWS to expose all the components I need to host and run service bar, it would be in my best interest to have those resources replicated to another zone or even a completely different region. If, for instance, region A experiences an outage (such as an internal failure, earthquake, hurricane or similar), I still would continue to provide service bar from region B (a standard failover procedure).

Every server or virtual instance in the public cloud is accessible via a public IP address. Using features like Amazon's Virtual Private Cloud (VPC), users are able to provision isolated virtual networks logically to host their AWS resources. And although a VPC is restricted to a particular region, there are methods by which one private network in one region can peer into the private network of another region.

Storage

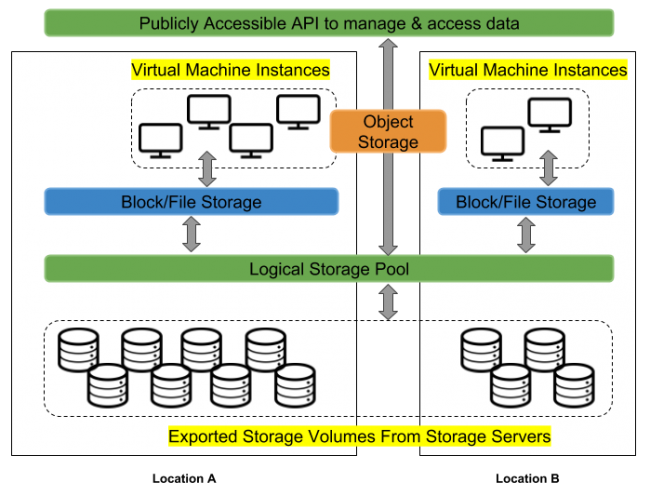

When it comes to storage in the cloud, things begin to get interesting. At first glance and without any explanation, the illustration shown in Figure 1 may appear somewhat complicated, but I still ask that you take a moment to study it.

Figure 1. A High-Level Overview of a Typical Storage Architecture in the Cloud

At the bottom, there are storage servers consisting of multiple physical storage devices or hard drives. There will be multiple storage servers deployed within a single location. Those physical volumes are then pooled together either within a single location or spanning across multiple locations to create a logical volume.

When a user requests a data volume for either a virtual machine instance or even to access it across a network, that volume of the specified size will be carved out from the larger pool of drives. In most cases, users can resize data volumes easily and as needed.

In the cloud, storage is presented to users in a few ways. First is the traditional block device or filesystem, following age-old access methods, which can be mapped to any virtual machine running any operating system of your choice. These are referred to as Elastic Block Storage (EBS) and Elastic File System (EFS) on AWS. The other and more recent method is known as object storage and is accessible over a network via a REpresentational State Transfer (REST) API over HTTP.

Object storage differs from block/filesystem storage by managing data as objects. Each object will include the data itself, alongside metadata and a globally unique identifier. A user or application will access this object by requesting it by its unique identifier. There is no concept of a file hierarchy here, and no directories or subdirectories either. The technology has become quite standard for the more modern web-focused style of computing. It is very common to see it used to store photos, videos, music and more. Mentioned earlier, the AWS object solution is referred to as S3.

Virtualization

The key to the cloud's success is centered around the concept of Infrastructure-as-a-Service (IaaS) and its capabilities to serve virtual machines via a hypervisor's API. A hypervisor allows you to host multiple operating systems (that is, virtual machines) on the same physical hardware. Most modern hypervisors are designed to simulate multiple CPU architectures, which include Intel (x86 and x86-64), ARM, PowerPC and MIPS. In the case of the cloud, through a web-based front end, you are in complete control of all your allocated computing resources and also are able to obtain and boot a new server instance within minutes.

Think about it for a second. You can commission a single server or thousands of server instances simultaneously and within minutes—not in hours or days, but minutes. That's pretty impressive, right? All of this is controlled with the web service Application Program Interface (API). For those less familiar, an API is what glues services, applications and entire systems together. Typically, an API acts as a public persona for a company or a product by exposing business capabilities and services. An API geared for the cloud can be invoked from a browser, mobile application or any other internet-enabled endpoint.

With each deployed server instance, again, you are in full control. Translation: you have root access to each one (with console output) and are able to interact with them however you need. Through that same web service API, you are able to start or stop whichever instance is necessary. Cloud service providers allow users to select (virtual) hardware configurations—that is, memory, CPU and storage with drive partition sizes. Users also can choose to install from a list of multiple operating systems (including Linux distributions and Microsoft Windows Server) and software packages. And finally, it's worth noting, the more resources selected, the more expensive the server instance becomes.

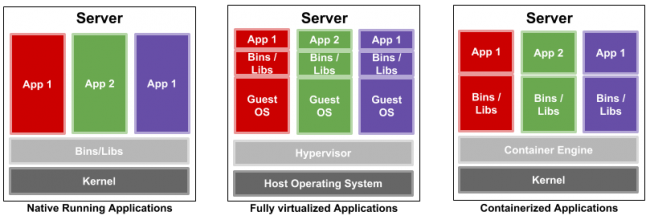

Figure 2. Illustrating the Difference between Running Applications on Bare-Metal Systems, Hypervisors and Containers

Containers

Containers are about as close to bare metal that you can get when running virtual machines. Hosting virtual machines imposes very little to no overhead. This feature limits, accounts for and isolates CPU, memory, disk I/O and network usage of one or more processes. Essentially, containers decouple software applications from the operating system, giving users a clean and minimal operating environment while running everything else in one or more isolated "containers".

This isolation prevents processes running within a given container from monitoring or affecting processes running in another container. Also, these containerized services do not influence or disturb the host machine. The idea of being able to consolidate many services scattered across multiple physical servers into one is one of the many reasons data centers have chosen to adopt the technology. This method of isolation adds to the security of the technology by limiting the damage caused by a security breach or violation. An intruder who successfully exploits a security hole on one of the applications running in that container is restricted to the set of actions possible within that container.

In the context of the cloud, containers simplify application deployment immensely by not only isolating the application from an entire operating system (virtualized or not) but also by being able to deploy with a bare minimum amount of requirements in both software and hardware, further reducing the headache of maintaining both.

Serverless Computing

Cloud native computing or serverless computing are more recent terms describing the more modern trend of deploying and managing applications. The idea is pretty straightforward. Each application or process is packaged into its own container, which, in turn, is orchestrated dynamically (that is, scheduled and managed) across a cluster of nodes. This approach moves applications away from physical hardware and operating system dependency and into their own self-contained and sandboxed environment that can run anywhere within the data center. The cloud native approach is about separating the various components of application delivery.

This may sound identical to running any other container in the cloud, but what makes cloud native computing so unique is that you don't need to worry about managing that container (meaning less overhead). This technology is hidden from the developer. Simply upload your code, and when a specified trigger is enabled, an API gateway (maintained by the service provider) deploys your code in the way it is intended to process that trigger.

The first thing that comes to mind here is Amazon's AWS Lambda. Again, under this model, there's no need to provision or manage physical or virtual servers. Assuming it's in a stable or production state, simply upload your code and you are done. Your code is just deployed within an isolated containerized environment. In the case with Lambda, Amazon has provided a framework for developers to upload their event-driven application code (written in Node.js, Python, Java or C#) and respond to events like website clicks within milliseconds. All libraries and dependencies to run the bulk of your code are provided for within the container.

As for the types of events on which to trigger your application, Amazon has made it so you can trigger on website visits or clicks, a REST HTTP request to their API gateway, a sensor reading on your Internet-of-Things (IoT) device, or even an upload of a photograph to an S3 bucket.

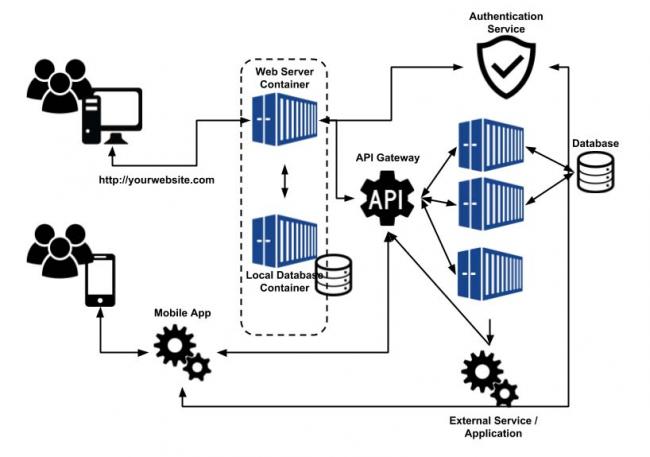

Figure 3. A Typical Model for Cloud Native Computing

Now, how do all these components come together? It begins with users accessing your service through a website or via an application on their mobile devices. The web server and the various components on which it relies may be hosted from locally managed containers or even virtual machines. If a particular function is required by either the web server or the mobile application, it will reach out to a third-party authentication service, such as AWS Identity and Access Management (IAM) services, to gain the proper credentials for accessing the serverless functions hosted beyond the API gateway. When triggered, those functions will perform the necessary actions and return with whatever the web server or mobile application requested. (I cover this technology more in-depth in Part II.)

Security

It's generally assumed that private cloud and on-premises solutions are more secure than the public cloud options, but recent studies have shown this to not be the case. Public cloud service providers spend more time and resources consulting with security experts and updating their software frameworks to limit security breaches. And although this may be true, the real security challenge in leveraging public cloud services is using it in a secure manner. For enterprise organizations, this means applying best practices for secure cloud adoption that minimizes lock-in where possible and maximizes availability and uptime.

I already alluded to identity and authentication methods, and when it comes to publicly exposed services, this feature becomes increasingly important. These authentication services enable users to manage access to the cloud services from their providers. For instance, AWS has this thing called IAM. Using IAM, you will be able to create and manage AWS users/groups and with permissions that allow/deny their access to various AWS resources or specific AWS service APIs. With larger (and even smaller) deployments, this permission framework simplifies global access to the various components making up your cloud. It's usually a free service offered by the major providers.

Summary

It's fair to say that this article covers a lot: a bit about what makes up the cloud, the different methods of deployment (public, private and hybrid) and the types of services exposed by the top cloud-service providers, followed by a general overview of how the cloud is designed, how it functions and how that functionality enables the features we enjoy using today.

In Part II of this series, I further explore the cloud using real examples in AWS. So, if you haven't done so already, be sure to register an account over at AWS. Charges to that account may apply.