The Digital Unconformity

Will our digital lives leave a fossil record? Or any record at all?

In the library of Earth's history, there are missing books. All were written in rock that is now gone. The greatest example of "gone" rock first was observed by John Wesley Powell in 1869, on his expedition by boat through the Grand Canyon. Floating down the Colorado river, he saw the canyon's mile-thick layers of reddish sedimentary rock resting on a basement of gray non-sedimentary rock, and he correctly assumed that the upper layers did not continue from the bottom one. He knew time had passed between the basement rock and the floors of rock above it, but he didn't know how much. The answer turned out to be more than a billion years. The walls of the Grand Canyon say nothing about what happened during that time. Geology calls that nothing an unconformity.

In fact, Powell's unconformity prevails worldwide. The name for this worldwide missing rock is the Great Unconformity. Because of that unconformity, geology knows comparatively little about what happened in the world through stretches of time ranging regionally up to 1.6 billion years. All of those stretches end abruptly with the Cambrian Explosion, which began about 541 million years ago. Many theories attempt to explain what erased all that geological history, but the prevailing paradigm is perhaps best expressed in "Neoproterozoic glacial origin of the Great Unconformity", published on the last day of 2018 by nine geologists writing for the National Academy of Sciences.

Put simply, they blame snow. Lots of it—enough to turn the planet into one giant snowball, already informally called Snowball Earth. A more accurate name for this time would be Glacierball Earth, because glaciers, all formed from snow, apparently covered most or all of Earth's land during the Great Unconformity—and most or all of the seas as well.

The relevant fact about glaciers is that they don't sit still. They spread and slide sideways, pressing and pushing immensities of accumulated ice down on landscapes that they pulverize and scrape against adjacent landscapes, abrading their way through mountains and across hills and plains like a trowel spreading wet cement. Thus, it seems glaciers scraped a vastness of geological history off the Earth's surface and let plate tectonics hide the rest of the evidence. As a result, the stories of Earth's missing history are told only by younger rock that remembers only that a layer of moving ice had erased pretty much everything other than a signature on its work.

I bring all this up because I see something analogous to Glacierball Earth happening right now, right here, across our new worldwide digital sphere. A snowstorm of bits is falling on the virtual surface of that virtual sphere, which itself is made of bits even more provisional and temporary than the glaciers that once covered the physical Earth. All of this digital storm, vivid and present in our current moment in time, is not only doomed to vanish, but it lacks even a glacier's talent for accumulation.

There is nothing about a bit that lends itself to persistence, other than the media it is written on, if it is written at all. Form follows function, and right now, most digital functions, even those we call "storage", are temporary. The largest commercial facilities for storing digital goods are what we fittingly call "clouds". By design, these are built to remember no more of what they contained than does an empty closet. Stop paying for cloud storage, and away goes your stuff, leaving no fossil imprints. Old hard drives, CDs and DVDs might persist in landfills, but people in the far future may look at a CD or a DVD the way a geologist today looks at Cambrian zircons: as signatures of digital activity in a lost period of time. If those fossils speak of what's happening now at all, it will be of a self-erasing Digital Earth that began in the late 20th century.

This isn't my theory. It comes from my wife, who has long claimed that future historians will look on our digital age as an invisible one, because it sucks so royally at archiving itself. I think she's right.

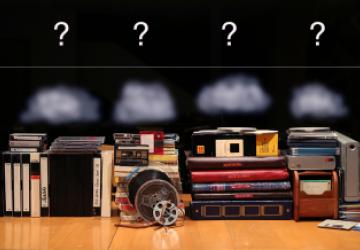

For example, this laptop currently sits atop a stack of books on my desk. Two of those books are self-published compilations of essays I wrote about technology in the mid-1980s, mostly for publications that are long gone. The originals are on floppy disks that can be read only by PCs and apps of that time, some of which are buried in lower strata of boxes in my garage. I just found a floppy with some of those essays. (It's the one with a blue edge in the wood case near the right end of the photo above.) But I'll need to find an old machine to read it. Old apps too, all of them also on floppies. If those still retain readable files, I am sure there are ways to recover at least the raw ASCII text. But I'm still betting the paper copies of the books under this laptop will live a lot longer than the floppies or the stored PCs will—if those aren't already bricked by decades of un-use.

As for other media, the prospect isn't any better.

At the base of my video collection is a stratum of VHS videotapes, atop of which are strata of Video8 and Hi8 tapes, and then one of digital stuff burned onto CDs and stored in hard drives, most of which have been disconnected for years. Some of those drives have interfaces and connections no longer supported by any computers being made today. Although I've saved machines to play all of them, none I've checked still work. One choked to death on a CD I stuck in it. And that was just one failure among many that stopped me from making Christmas presents of family memories recorded on old tapes and DVDs. I may take up the project again sometime before next Christmas, but the odds are long against that (hey, I'm busy) and short toward the chance that nobody will ever see or hear those recordings again. And I'm not even counting my parents' 8mm and 16mm movies made from the 1930s to the 1960s. In 1989, my sister and I had all of those copied over to VHS tape. We then recorded my mother annotating the tapes onto companion cassette tapes while we watched the show. I still have the original film in a box somewhere, but I can't find any of the tapes.

The base stratum of my audio past is a few dozen open reel tapes recorded in the 1950s and 1960s. Above that are cassette and microcassete tapes, plus some Sony MiniDisks recorded in ATRAC, a proprietary and incompatible compression algorithm now used by nobody, including Sony. Although I do have ways to play some (but not all) of those, I'm cautious about converting any of them to digital formats (Ogg, MPEG or whatever), because all digital storage media becomes obsolete, dies, or both—as do formats, algorithms and codecs. Already I have dozens of dead external hard drives in boxes and drawers. And no commercial cloud service is committed to digital preservation in perpetuity in the absence of payment. This means my saved files in clouds are sure to be flushed after neither my heirs nor I continue paying for their preservation.

Same goes for my photographs. My old photographs are stored in boxes and albums of photos, negatives and Kodak slide carousels. My digital photographs are spread across a mess of duplicated back-up drives totaling many terabytes, plus a handful of CDs. About 60,000 photos are exposed to the world on Flickr's cloud, where I maintain two Pro accounts (here and here) for $50/year a piece. More are in the Berkman Klein Center's pro account (here) and Linux Journal's (here). It is unclear currently whether any of that will survive after any of those entities stop paying the yearly fee. SmugMug, which now owns Flickr, has said some encouraging things about photos such as mine, all of which are Creative Commons-licensed to encourage re-use. But, as Geoffrey West tells us, companies are mortal. All of them die.

As for my digital works as a whole (or anybody's), there is great promise in what the Internet Archive and Wikimedia Commons do, but there is no guarantee that either will last for decades more, much less for centuries or millennia. And neither are able to archive everything that matters (much as they might like to).

It also should be sobering to recognize that we only rent the "sites", "locations" and "addresses" at "domains" that we talk about "owning". The plain and awful fact is that nobody "owns" a domain on the internet. They pay a sum to a registrar for the right to use a domain name for a finite period of time. There are no permanent domain names or IP addresses. In the digital world, finitude rules.

So the historic progression I see, and try to illustrate in the photo at the beginning of this article, is from hard physical records through digital ones we hold for ourselves, and then up into clouds that go away, inevitably. Everything digital is snow falling and disappearing on the waters of time.

Will there ever be a way to save for the very long term what we ironically call our digital "assets" for more than a few dozen years? Or is all of it doomed by its own nature to disappear, leaving little more evidence of its passage than a digital unconformity?

I can't think of any technical questions more serious than those two.