Linux for Suits - Independent Identity

I've been delivering the closing keynote at Digital ID World (DIDW) since October 2002, when the show began. I've given it five times so far. From the beginning I've had a case to make. Here it is:

In a truly free marketplace, vendors in a category compete openly for a customer's business, based on information the customer supplies at his or her discretion to any or all of them. Customer data isn't isolated in vendor silos, and customers aren't forced to go from one silo to another and interact separately with each vendor's customer relationship management system, its lame marketing agendas and its locked-up data.

Customers won't have full power in any marketplace unless they control their own data, including data about their relationships with vendors, and selectively make private data available to vendors, with explicit permissions regarding each vendor's use of it. Drummond Reed of Cordance and Identity Commons calls this CoRM, or company relationship management.

Personal identity control and CoRM are powers customers have not experienced since the Industrial Age began and they first became “consumers”. As fully empowered customers, they will blow the CRM blinders off vendors, release a wave of entrepreneurship, differentiation and innovation and make markets grow in all directions. This won't be a market revolution but, rather, the dawn of a real market—where demand and supply have equal power.

CoRM requires identity services that do not yet exist. Those services also serve other purposes—SSO, or single sign-on, authentication, security, privacy and so on. But whatever those services may be, they share a point of origin: the individual. This invites adjectives such as grass-roots, lightweight, user-centric, next-generation, human origin, bottom-up and distributed. I like the literal meaning of the word independent. Every speech I make on this subject is a literal declaration of customer independence.

Independent Identity is a human quality more than an organizational one. Establishing and ubiquitizing Independent Identity therefore needs to be a grass-roots movement that grows on open standards and with support from the Open Source community. For that reason, it only makes sense for Independent Identity to grow from the bottom up rather than from the top down, from individuals rather than from organizations.

Andre Durand of Ping Identity Corp., on whose advisory board I now serve, inspired this thinking in 2001, when he was putting the company together. I wrote about Andre and Ping in “Identity from the Inside Out”, in the May 2002 issue of Linux Journal. In it I describe Andre's three-tier view of identity:

At the center is tier one: that's your core identity alone. You're in charge of it. Outside that is tier two. This is the identity issued to you by the government, by retailers, by airlines, by insurance companies, by credit-card companies. Every piece of plastic in your wallet is a tier-two identity. Tier three is the cloud of highly presumptuous identity information held by direct marketers and others who hope you may be the one consumer in 50 who responds to a promotional message.

When Andre laid this out for me the first time, I knew instantly that we could liberate markets simply by developing the means for individuals to assert their sovereign identities. It was a moment of revelation—like Neo had, just before he said “It's about choice” to the architect of The Matrix. In fact, The Matrix, one of my favorite movies ever, suddenly made sense as an allegory for the false world invented by marketing, where consumers live in blissful ignorance of their role as batteries whose energy maintains that world.

By the middle of 2004, however, I had begun to lose faith. Even Ping Identity was caught up with the rest of the supply side in a conversation about federation. In an interview last year, Eric Norlin, Director of Marketing at Ping Identity, said federation “leaves the distributed environment as it is, but seeks to let end users link together those pieces and still have control over their privacy, what gets shared, and how.” He said the Liberty Alliance spec, for example, “is purposefully designed to be opaque. [It] tries to accomplish one thing...to allow one end user to link one account to another account. But in order to protect the privacy of the end user...neither side of that account—either Company A or Company B—would know who the end user is that is being passed between them.”

I've summarized this as “large companies having safe sex using customer data”.

Federation is a big company concern, essentially a silo-to-silo “solution”—so far. Liberty Alliance isn't the only consortium devoted to federation. The other big one is WS-I, where WS stands for Web services. WS-I was founded by Microsoft, IBM and Verisign, partly in response to the Liberty Alliance, which was founded by Sun, partly in response to Microsoft's Passport. Anyway, the more I heard about federation, the more depressed I became about the prospects for Independent Identity.

Then, during LinuxWorld Expo in August 2004, I met Kaliya (“Identity Woman”) Hamlin at a San Francisco Giants baseball game. She told me she worked with Identity Commons, a grass-roots organization with a market-opening plan that leveraged some standards, notably XRI and XDI, and encouraged new ones, such as i-Names. A series of conversations with various Identity Commons people armed me with plenty of fodder for my keynote at DIDW in October 2004. I wrote up the story behind that keynote in “What's Your i-Name?”, my column for the January 2005 issue of Linux Journal. In that piece, I made something of a bet about Independent Identity: “We're not going to get that from the big vendors, for the same reason we didn't get Linux from big computer makers: big suppliers in any category have trouble pioneering anything that's good for everybody and not only for them.”

I was wrong about that. When the conversation started to heat up after DIDW, the Neo role was being played by a character with the unlikely title of “Architect”, working inside the most unlikely company of all: Microsoft. Kim Cameron is his name, and his architecture is the Identity Metasystem. Note that I don't say “Microsoft's Identity Metasystem”. That's because Kim and Microsoft are going out of their way to be nonproprietary about it. They know they can't force an identity system on the world. They tried that already with Passport and failed miserably.

Kim came to Microsoft by way of acquisition, when Microsoft bought Zoomit, a Toronto company specializing in the “metadirectory” field. I came to know Kim through Craig Burton of The Burton Group, back in the early 1990s. Craig and his organization saw non-interoperable directories as a problem that could be solved only by a system that was intentionally inclusive and respectful toward all directories and their countless differences. Craig labeled the required system a metadirectory and called for vendors to fill the market's need for one. Kim and Zoomit stepped forward and developed a metadirectory product, along with a lot of deep thinking about directories and related issues, including security and identity. During that time I became good friends with Kim, an occasional consultant to Zoomit.

Microsoft acquired Zoomit at about the time it was becoming clear that Passport was failing. At Microsoft Kim took a leading role in re-thinking the company's approach to identity. It became clear to him that taking a “meta” approach would open a whole new marketplace—for Microsoft and everybody else:

At first I didn't think it was possible. But while I was scrounging around one day I ran across this one protocol that was so simple I could hardly believe it. I saw how it could work like a conduit for the simple exchange of tokens and how it could bridge many different identity systems.

Craig Burton took a natural interest in Kim's identity work at Microsoft. Before DIDW/2004, Craig began telling me that Kim's architecture had the potential to seed and support—in an open way—the kind of grass-roots movement I'm looking for.

So I made sure Kim got to connect with the other grass-roots advocates attending the conference: Drummond Reed, Fen LaBalme, Mark LeMaitre, Kaliya Hamlin, Jan Hauser and Owen Davis of Identity Commons and also, for several on that list, of Seattle-based Cordance; Dick Hardt of Sxip; Marc Canter, currently of Broadband Mechanics but perhaps best known as a founder of Macromind, which later became Macromedia; Simon Grice of MiDentity; and Phil Windley of Brigham Young University, also the former CIO of Utah and the author of a new book from O'Reilly on digital identity. All are open-source and open standards advocates, and all consider open-source involvement essential to the success of whatever it was Kim and Microsoft had in the works, which still wasn't clear at the time.

An informal group began to form. Meetings followed in Seattle and other places. And right after DIDW/2004, Kim also began posting his Seven Laws of Identity. He did this on an installment plan to give everybody time to talk about each one before moving on to the next. His First Law appeared on November 16, 2004, and his Seventh Law appeared in March 2005. In summary form, here they are:

User Control and Consent: digital identity systems must reveal information identifying a user only with the user's consent.

Limited Disclosure for Limited Use: the solution that discloses the least identifying information and best limits its use is the most stable, long-term solution.

The Law of Fewest Parties: digital identity systems must limit disclosure of identifying information to parties having a necessary and justifiable place in a given identity relationship.

Directed Identity: a universal identity metasystem must support both “omnidirectional” identifiers for use by public entities and “unidirectional” identifiers for private entities, thus facilitating discovery while preventing unnecessary release of correlation handles.

Pluralism of Operators and Technologies: a universal identity metasystem must channel and enable the interworking of multiple identity technologies run by multiple identity providers.

Human Integration: a unifying identity metasystem must define the human user as a component integrated through protected and unambiguous human-machine communications.

Consistent Experience across Contexts: a unifying identity metasystem must provide a simple consistent experience while enabling separation of contexts through multiple operators and technologies.

The Laws serve two purposes. The first is to guide conversation and development in an emerging marketplace. The second is to guide conversation and development inside Microsoft. Kim says he often finds himself saying stuff like, “No, that would break the Fifth Law” or “That misses the point of the Seventh Law.”

Microsoft is and will remain an issue. In October and November 2004, Marc Canter and others wondered out loud about how we could ever trust the company or its partners, such as Sun Microsystems. Craig Burton acknowledged the problem in a December 4th blog posting:

Marc contends that people don't want to get locked into standards owned by Microsoft or Sun. Kim wants to look beyond the past and create a “big bang” of distributed computing that would eclipse the petty Microsoft bashing. In Marc's defense, Microsoft is an unabashed bully. The leaders of Microsoft—Bill Gates and Steve Ballmer—lead the bully behavior. I have personal experience of this behavior from both of them. Microsoft doesn't and isn't going to play fair anytime in the future—in general.

Perspective: Craig fought Microsoft when he was at Novell in the 1980s—and usually won. One high-level Microsoft executive told me years later that Craig was perhaps the only leader at a competing company that truly understood how to compete and win against Microsoft. Craig continues:

I say “in general” for a reason. There are good people with vision and integrity at Microsoft. Kim Cameron is one of those people. You can't go wrong working with Kim. Further, it is just ludicrous to think that Microsoft is of one voice and has an overarching plan with which to rule everything always and forever....I have said before to Kim that working at Microsoft is like working inside ten tornadoes. I am changing that to a thousand tornadoes. Each tornado (or hailstorm if you like) has its own path, thinking and objective. They seldom cross paths and are too busy dealing with the issues at hand to even talk to each other. Microsoft is a thousand tornadoes deep.

Microsoft bashing aside, when two people like Marc and Kim get together and collaborate, expect good things to happen that go beyond the history of giants—even the giant of all time—Microsoft.

The most significant push-back we received was from Dave Winer, whom Kim considered to be an important role model. Dave had success at launching standards, including XML-RPC, SOAP—which Dave and his company, Userland, co-developed with Microsoft—and RSS, and he made it all happen without the clout of a large organization behind him. RSS was an especially interesting case, because it established a service, syndication, that is rapidly moving toward ubiquity.

On his blog, Scripting News, Dave wrote:

Doc Searls...offered RSS and podcasting as examples of technologies that were simple, therefore successful, and suggests that identity, if it were to be approached the same way, might have similar success. Bzzzt. Wrong. RSS was not easy, it was hard, for exactly the same reasons identity is hard. Too many cooks spoil the broth. Two ways to do identity is one too many.

Politics spoiled identity and would have spoiled RSS had the major players not converged on RSS 2.0. The difference this time was that there was a Switzerland, me, to guide RSS through its gauntlet, and I clearly wasn't in bed with any of the major publishers or vendors. The Harvard connection didn't hurt because it's a highly respected university that hadn't been involved in tech standards. Had identity had that kind of champion-ship it might not be the mess it is today.

I didn't think identity was spoiled in the least. But I also realized something. Identity needs a Dave Winer: an independent developer and free-range technologist who tirelessly advocates something that can work for everybody.

On December 30th, Steve Gillmor called. He was hunting up guests for the “Gillmor Gang” scheduled the next day: New Year's Eve. I suggested bringing in the “Identity Gang”—or as many as wanted to come on the show. Steve said yes, and I sent out an e-mail to nine people, including Dave Winer, whose experience, example and skepticism I thought were essential. To my surprise, nearly all of them, including Dave, agreed and took part in the show.

The conversation was all over the place. But it served as a public meeting to which many could listen and link. The “Identity Gang” show was energizing. Starting on January 1, 2005, I saw Independent Identity issues being discussed—not only in blogs and podcasts but in trade pubs and in halls at conferences—with considerable optimism. In the past, discussions always seemed to go sideways into energy-draining digressions on privacy, crypto and other muddy subjects, such as “Microsoft Sucks”.

Kim bled off a lot of steam by publishing his Fifth Law on New Year's Day. Craig Burton wrote this about it:

The Law of Pluralism is contrary to the laws of customer control.

Let's be clear: the Law of Pluralism requires operating system independence—by definition. This means the Microsoft Identity Architect is calling for a system that is not necessarily Windows-centric by design. This—of course—is the only way such a system can really work. But consider the implications.

A cross-platform identity metasystem is sun-spot hot and—with the other laws being discussed here—changes everything.

The Identity Metasystem looked to each of us—so far as we could understand it, which wasn't enough—as though it had the makings of a Net-native system that would embrace and accommodate everybody's separate efforts. It helped especially that Drummond Reed and the Identity Commons people already were figuring out ways of working with the Identity Metasystem.

Kim also demonstrated InfoCards, a Microsoft identity implementation that can work within the Metasystem. Everybody was eager to think about or find other implementations—so nobody would confuse the InfoCard implementation with the Identity Metasystem architecture. At one point I asked if it was possible for InfoCards, or anything Microsoft was doing in the Identity Metasystem framework, to plug in to Firefox. Kim said, “Yes, of course.” I invited Mitchell Baker to the next meeting we held, and she and Kim agreed that it ought to be workable.

The Identity Gang has grown since then. DIDW gave us a room to use on May 8th, the day before the show started. About 40 people met all day around a large table. Kim explained the Identity Metasystem in more detail than we had heard before. There was a lot of discussion, including plenty of skepticism, but more than enough positive energy to keep everybody interested.

Since then, Kim and his team have published a whitepaper titled “Microsoft's Vision for an Identity Metasystem”. The paper outlines the architecture in some detail. Here are the key paragraphs:

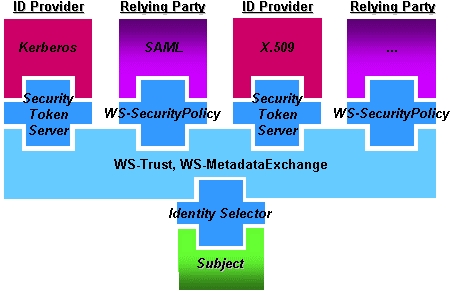

The encapsulating protocol used for claims transformation is WS-Trust. Negotiations are conducted using WS-MetadataExchange and WS-SecurityPolicy. These protocols enable building a technology-neutral identity metasystem and form the “backplane” of the identity metasystem. Like other Web services protocols, they also allow new kinds of identities and technologies to be incorporated and utilized as they are developed and adopted by the industry.

To foster the interoperability necessary for broad adoption, the specifications for WS-* are published and are freely available, have been or will be submitted to open standards bodies and allow implementations to be developed royalty-free.

Deployments of existing identity technologies can be leveraged in the metasystem by implementing support for the three WS-* protocols above. Examples of technologies that could be utilized by way of the metasystem include LDAP claims schemas; X.509, which is used in Smartcards; Kerberos, which is used in Active Directory and some UNIX environments; and SAML, a standard used in inter-corporate federation scenarios.

Figure 1 shows the graphic illustration.

Figure 1. The WS-* Architecture

The Independent Identity would be one of the ID providers, part of the metasystem. It could be hosted locally, on a Linux box in the clouds, on a phone—wherever someone wanted to put one.

I've told Kim that he and Microsoft need to do more before my constituency—the Linux and Open Source development communities—takes a serious interest in the Identity Metasystem. I said, “If you don't have an open-source license or if you start talking about IP Frameworks, my readers will leave the room.” The term IP Frameworks was used by somebody from another part of Microsoft, in respect to the WS-* standards process. Kim replied:

It's essential to have the Open Source community involved. And I wish we were already at some point in the future when we have some of these things cleared up. But we're talking about slow processes here. The standards process is incredibly complicated. You get a bunch of companies together, and the process is like nuclear disarmament. The only way to get a royalty-free standard is to negotiate IP in such a way that nobody can sue because it's a standoff. What an “IP Framework” means to me—though I am not a lawyer and can's speak for Microsoft on IP issues—is that everybody puts their IP in and agrees not to charge royalties. Ironically, the biggest concern may not be each company's IP, but submarine patents that can surface later and screw up everybody.

As for open-source licensing, Kim has said encouraging things to me privately, but for now there's nothing to report. I'm hoping, for everybody's sake, there will be an accepted open-source license or licenses in place by the time you read this.

Meanwhile, everybody in the open-source camp seems to be scratching their own itches, each in their own simplifying way.

Open ID says, “This is a distributed identity system, but one that's actually distributed and doesn't entirely crumble if one company turns evil or goes out of business.” Its identities are URL-based.

LID's goal is to “empower individuals to keep control over and manage their digital identities, using VCards, FOAF and GPG. It is very REST-ful and fully decentralized. It is also a great mechanism to add accountability to REST-based Web services, even if no (human) digital identities are involved.” Johannes Ernst, one of LID's creators, says “it's the simplest scheme there is, so simple that, just like a few other folks have done already, you can probably implement it yourself over the weekend and add five new profiles to it that we didn't even think of.” There are several LAMP and J2EE implementations available for download.

Sxip is more ambitious and has several parts. Sxip.net (Sxip Network) is “a simple, secure and open digital identity network that offers a user-centric and decentralized approach to identity management. This key piece of Internet infrastructure, based on a network architecture similar to DNS, can be used by people to develop their own identity management solutions, enabling distinct and portable Internet identities.” Sxip.com (Sxip Identity) “provides identity management solutions that leverage the Sxip Network and drive Identity 2.0 infrastructure. Sxip empowers individuals to create and manage their on-line digital identities and enables enterprises to instantly provision and manage their users.” Sxip.org provides developer resources, including a Subversion code repository.

Moebius “builds on the success of e-mail-based identity systems by adding a few important but incremental improvements while laying the foundation for more advanced identity systems in the future. Moebius is more convenient to use, easier to deploy and safer for all concerned, without requiring expensive investments in new infrastructure or adoption of untried, centralized identity systems.” Editors' Note: Moebius has changed its name to Passel.

There are other open-source and Linux-related efforts around identity, and I'm sure this article will flush out those who feel offended by their exclusion. I invite them to join the Identity Gang or whatever name it uses by the time you read this.

Things are moving so fast, in so many directions at once and with so many individuals involved, that it's impossible to cover the subject completely. This piece sets a record of frustration for me, personally. I've been working on it since January, and I've rewritten it countless times. I was going through a series of rewrites when I missed my deadline last month. And I almost decided to make it a Linux Journal Web site piece several days ago, when I still wasn't sure if Kim and his Identity Metasystem would take the heat from interested skeptics like Julian Bond and Dave Smith—or from those of us (a percentage that rounds to “everybody”) who see a lock-in agenda behind every Microsoft move. So I posted some tough public questions on IT Garage. Kim has met every challenge with grace, humor and backbone. I'm sure he needs all three to make this project fly inside Microsoft.

I also want to thank Microsoft for giving Kim a way to apply his genius. If this thing flies, high fives are due all around.

The best any of us can do is stay true to our own principles and purposes. Kim's are embodied in his “meta” understanding of the world. The man is the best includer I've ever known. Microsoft is lucky in the extreme to have him working there. Mine are embodied in an NEA understanding of the Net—as something Nobody can own, Everybody can use and Anybody can improve.

There is an improvement I want to see, and it's something only Independent Identities can produce. I want anybody to be able to pay for anything on a voluntary basis, because I believe the voluntary ability to pay whatever one wants is at the heart of a free and open marketplace. I also believe we haven't experienced that power since the Industrial Revolution put huge suppliers in charge, even of democratic governments. We certainly haven't had it since the invention of the price tag.

I'm not saying I want to turn every store into a commodities pit where everybody haggles over prices. I'm not saying “Let's get rid of fixed prices.” I am saying, let's give consumers the power to be customers. I am saying, let's start by making this work in markets where no prices have yet been set, where sellers and buyers don't yet have the means for discovering what their goods are worth, where—because that mechanism is absent—most of the goods are free, as in beer.

I have two markets in mind: “podsafe” (non-RIAA, Creative Commons-licensed) music and podcasts. I would like to be able to express my willingness to pay for music I like and for podcasts I like and to do that at my discretion, quickly and easily. And, to extend that ability to other services that welcome voluntary payment, such as public radio and TV, churches, charities and so on.

I would like that capability to be built in to my browser, as a plugin probably, and my RSS aggregator. Later, I'd like to see it in cell phones and other mobile devices.

I would like the Open Source community to step into those markets with me and say, “We have a way that anybody can pay anybody for anything, on their own or mutually agreeable terms.” And free has to be an alternative. Free still has to be okay.

You might say I'm talking about a more robust shareware market here. One where suppliers don't beg or cajole, make goods scarce or call those who get goods for free “pirates”. I'm talking about making the Net as open and responsible as a farmers market: a place where customers are as unlikely to filch from an artist's site as they are to take an apple from a farmer's cart. And where artists of all kinds still can give away all they like.

Can this be done? I don't know. I can think of a hundred reasons why it can't. I'm sure the rest of you can think of more. Between me writing the last sentence and this one, Johannes Ernst wrote this to me:

The trouble though, is, that we are miles away from being able to understand what the technical requirements are for such a transformational system, because we haven't thought through the transformational applications that need to be supported.

Yet I feel certain there's a way of doing this, and experimenting with it, and seeing what works and what doesn't, and showing the world how a free and open marketplace can work.

I want to give the old choose-your-silo system a bad case of Innovator's Dilemma. We need something disruptive here. Something simple and new. An invention that mothers necessity.

We won't get it if we get bogged down in long-winded digressions about privacy and crypto and the big awful companies that want to keep their hands—oops, credit and membership cards—in our pockets. Those are legitimate and necessary concerns, but they are secondary to the purpose of establishing methods and protocols and technologies for the assertion of Independent Identity. And for changing the world by saving markets from the producerist mentality that has kept everybody, producers included, in darkness for more than a century.

I also feel certain that forces far more nefarious than Microsoft are hell-bent on putting the Net genie back in the telco and cableco bottles—and turning it into the distribution system for “protected content” they imagined when they made sure the “information superhighway” had asymmetrical driveways to every “consumer's” home.

If we don't want that, we have to show we're customers and not just consumers. And real customers don't just shop in silos.

Resources for this article: /article/8401.

Doc Searls is senior editor of Linux Journal.