Web Reporting with MySQL, CSS and Perl

In the March 2005 issue of Linux Journal, I used Maypole to create a Web-based database application in only 18 lines of Perl code. The functionality provided by Maypole is impressive except in one important area: reporting. Consequently, I started to research technologies for producing reports from my Soccer Club system. My goal was to provide a set of standard reports that could be executed from a Web interface.

Web reports can be produced in a lot of ways using any of the many server-side programming technologies, such as PHP, JSPs, Perl scripts and the like. Standalone desktop reporting tools also are available, and it's even possible to use OpenOffice.org to report on a MySQL database. As my reporting requirements are basic, however, I wanted to keep my intellectual effort to the minimum. What I didn't mind doing was spending time crafting the SQL queries that I'd need to produce my reports. Once written, I wanted my SQL query to produce an HTML table of results.

I can do this with Perl, of course, using the DBI and DBD::mysql modules, hand-crafting program code to send the query to the database. I then could post-process the results with more code, before—ultimately—writing yet more code to create the table. For my simple requirements, this felt like too much work. What I really wanted was a quick-and-dirty solution. In the remainder of this article, I detail the Web reporting solution I designed.

While browsing Paul DuBois' excellent MySQL Cookbook, I discovered a command-line option for turning the results of a command-line query into an HTML table (recipe 1.23, page 33). By way of example, consider the following command line:

mysql -e "select name from player" \

-u manager -ppwhere CLUB

which produces the following textual output when invoked:

+-------------+ |name | +-------------+ |Robert Plant | |Tim Finn | |James Taylor | |Bryan Adams | |Ian Gillen | |Mick Jagger | |Neil Young | |Bob Dylan | +-------------+

These results not only show the names of all of the players in the Soccer Club database, but they also appear to indicate that the club's players are named after some famous folk and rock singers. When re-run with the HTML creation option, like so:

mysql -H -e "select name from player" \

-u manager -ppwhere CLUB

the above command line produces the following, which, trust me, is an HTML table:

<TABLE BORDER=1><TR><TH>name</TH></TR><TR><TD> Robert Plant</TD></TR><TR><TD>Tim Finn</TD></TR> <TR><TD>James Taylor</TD></TR><TR><TD>Bryan Adams </TD></TR><TR><TD>Ian Gillen</TD></TR><TR><TD> Mick Jagger</TD></TR><TR><TD>Neil Young</TD></TR> <TR><TD>Bob Dylan</TD></TR></TABLE>

It is possible to put the SQL query into a file and then refer to the file on the command line. For example—and assuming the above query is in a file called name.sql—this command line produces the same HTML table:

mysql -H -u manager -ppwhere CLUB < name.sql

Knowing this much, I figured that if I could come up with a means of issuing the HTML-producing command line from a Web interface, I'd be most of the way toward providing my Web reporting solution. So, I wrote a small CGI script in Perl to execute the command line for me.

The strategy employed by my simple CGI script is straightforward: after determining the name of the query to execute, a command line is constructed and then issued by the CGI script. Any results produced from executing the command line are put inside the body part of the HTML page that the CGI script produces.

After the usual Perl startup lines, the runquery.cgi script starts by defining a series of constant values:

#! /usr/bin/perl -w use strict; use constant MYSQL => '/usr/bin/mysql'; use constant USERID => 'manager'; use constant PASSWD => 'pwhere'; use constant DBNAME => 'CLUB';

The location for the MySQL client on your computer may be different from where I have mine, so change the MYSQL constant value if need be. Also, note that I'm hard-coding the values for the database user (USERID), the password (PASSWD) and the database that is to be queried against (DBNAME). Although this may not be the best practice, I am going to explain it away by saying that this is the dirty part of my quick-and-dirty solution. With the constants defined, I indicate that I'm going to use the standard interface to Perl's CGI programming technology:

use CGI qw( :standard );

Two Perl scalars then are defined, taking their value from any parameters passed from a Web interface to the CGI script. The first parameter, called query, identifies the SQL file to use, while the second, called title, provides a report title to use when displaying results:

my $query = param( 'query' ); my $title = param( 'title' );

The script then creates the command line that runs the query through the MySQL client program. Note that Perl's dot operator is used to concatenate strings:

my $cmdline = MYSQL .

' -H -u ' .

USERID .

' -p' .

PASSWD .

' ' .

DBNAME .

"< $query ";

The script then starts to build an HTML page. The header function generates the correct Content-Type header, and the start_html function starts to create the HTML page using the value provided for the page's title:

print header; print start_html( -title => $title );

The next line of code uses Perl's qx operator to execute the command line and return any resulting output from its execution to a variable, called $results:

my $results = qx/ $cmdline /;

The rest of the script adds an HTML level 3 heading to the Web page, together with the query results and an HTML link to the reports page. The end_html function finishes the HTML page generation and concludes the script:

print "<h3>$title</h3>";

print $results;

print p, "Return to the ",

a( { -href => "/Club/Reports.html" },

"List of Reports" );

print end_html;

To run the script, you need to do two things: put the script in a place where your Web server can find it and put an SQL query into a file. On my Fedora Core 3 system running Apache 2, the /var/www/cgi-bin/ directory is used to hold the Web server's CGI scripts. So, I simply copy the CGI script into that location and make it executable:

cp runquery.cgi /var/www/cgi-bin/ chmod +x /var/www/cgi-bin/runquery.cgi

The above directory may not be the location used by your distribution for Web pages, so be sure to check first. As for a query, here's the contents of the file conditions.sql:

select player.name as 'Player',

condition.name as 'Medical Condition'

from player, condition

where player.medical_condition = condition.id and

player.medical_condition != 1;

The above SQL query joins the player and condition tables in order to list the names of each player together with his medical condition, assuming he has one. This query file also needs to be copied to the CGI directory on the Web server:

cp conditions.sql /var/www/cgi-bin/

To execute the query from the CGI script, type the following into your browser's address bar, substituting localhost with the name of your Web server:

https://localhost/cgi-bin/runquery.cgi? \

title=Results&query=conditions.sql

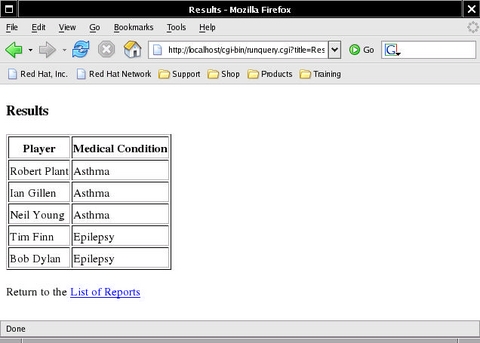

This URL produces the output shown in Figure 1, which, despite being a little plain, looks okay—but it could be nicer.

To produce a report with an improved look and feel, I created a small cascading style sheet (CSS), called reports.css, to improve the general appearance of the produced report:

body {

font-family: sans-serif;

}

table {

font-family: sans-serif;

background-color: LIGHTYELLOW;

}

table th {

background-color: LIGHTCYAN;

font-size: 75%;

}

h3 {

font-family: sans-serif;

color: BLUE;

}

As stylesheets go, mine is pretty simple. I declare a font for the text in my main body and then I fiddle with the font and background color of any tables that I put on my HTML page. The table headings are shown at 75% of the user's normal text size with a different background color from the data in the table. I then declare that my level 3 headings are colored blue.

The CSS file needs to be copied into the Web server's root directory so that my Web pages can find it:

cp reports.css /var/www/html

To use the CSS file, I changed the print start_html line from runquery.cgi to refer to the stylesheet, as follows:

print start_html( -title => $title,

-style => { -src => "/reports.css" } );

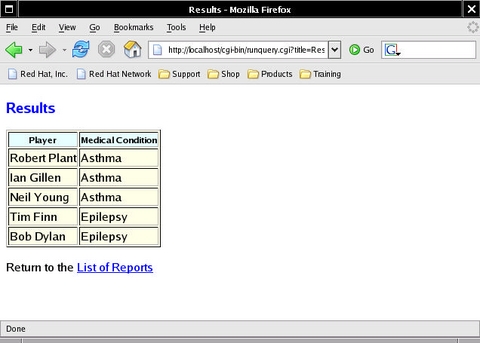

Reloading the query produces the output shown in Figure 2. It may not win me a Web design award, but it does look a whole lot better than the plain results shown in Figure 1.

This part of my solution was easy. All I needed was a simple Web page describing a list of reports. As with the generated reports, I use my simple stylesheet to improve the look of the reports page. Here's the HTML I used:

<HTML>

<HEAD>

<TITLE>Soccer Club Reporting System</TITLE>

<LINK rel="stylesheet" type="text/css"

href="/reports.css" />

</HEAD>

<BODY>

<H3>Soccer Club Reporting System</H3>

Choose from one of these reports:

<OL>

<LI>List players that have a

<a href="/cgi-bin/runquery.cgi?

title=Players with a Medical Condition&

query=conditions.sql">Medical Conditions</a>

<LI>List all players,

<a href="/cgi-bin/runquery.cgi?

title=Listing of all Players (Youngest First)&

query=desc_dob.sql">youngest first</a>

</OL>

Return to the <A HREF="/Club">Soccer Club</A>

database system.

</BODY>

</HTML>

As shown above, each report is executed with two parameters: title, which provides a report description, and query, which identifies the SQL query file to run through MySQL. With my Web page created, I copied it into the root directory of the Soccer Club Web site:

cp Reports.html /var/www/html/Club/

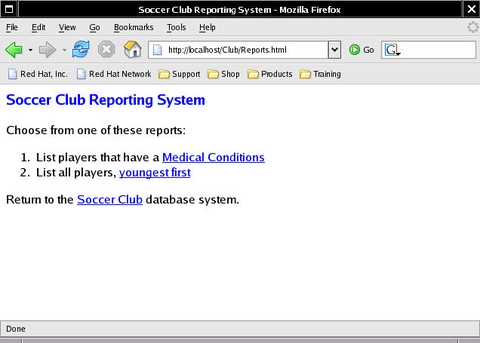

When loaded into a Web browser, the reporting Web interface looks like that shown in Figure 3.

At this point, I think I'm done. I have a simple Web interface to a standard report producing mechanism. If I write more queries, I can put them into their own SQL query file, copy the file to my cgi-bin directory and update my HTML reports Web page to invoke the query as required. My solution is quick-and-dirty and more than good enough.

Or is it?

The security of my solution is very, very poor. I need to worry about two things, protecting my CGI script and SQL query files from user tampering and protecting my system from the CGI script.

When it comes to tampering with the CGI script and SQL query files, the problem is—by default—all of the files can be read by any user logged in to the system that runs the Web server; a simple cat or less command would do the trick. Any user can look inside runquery.cgi and display the user ID and password used in accessing the database, which is not good.

The User and Group directives in the Apache httpd.conf configuration file indicate which user and group the Apache Web server runs under. On my computer, this user and group is set to apache. Knowing this, I issued the following commands to ensure that the contents of my CGI script and SQL query files are owned by the apache user and that they can be read from and written to only by the same apache user. This stops any other user—except root, of course—from examining their contents:

cd /var/www/cgi-bin chown apache:apache * chmod 600 * chmod 700 *.cgi

The first chmod command ensures the files in the cgi-bin directory can be read from and written to solely by the apache user. The second chmod command switches on the executable bit for any CGI scripts, but only for the owner of the file. With these simple precautions, my solution is now safe from user tampering.

The above chmod command lines protect the files from other users logged in to the system, but my solution still is vulnerable. Unfortunately, it is open to exploitation by any user with access to the Web server by way of any Web browser. For example, consider what happens if the following URL is sent to the CGI script:

https://localhost/cgi-bin/runquery.cgi? \ title=Ha!&query=conditions.sql | cat runquery.cgi

The contents of the CGI script appear in the browser, and the issuer easily can read the database name, the user ID and password contained within the file. This is bad enough, but imagine if the cat runquery.cgi pipe in the above URL is replaced with this:

cat /etc/passwd

or the potentially disastrous:

rm -rf /

The problem with the CGI script as written is it blindly trusts the issuer not to fiddle with the URL. By simply adding the pipe symbol and any other shell command line to the URL, the issuer exploits this poorly designed CGI script, effectively executing other commands of the issuer's choosing on the Web server. By passing the query string unaltered to the operating system to execute, the CGI script makes it far too easy for such a vulnerability to be exploited.

Thankfully, Perl has a special mode of operation that can help, and it is called taint mode. Most any book on Perl describes taint mode, and the second edition of Christiansen and Torkington's Perl Cookbook provides a handy primer (recipe 19.4, page 767). By turning on taint mode, the Perl interpreter is instructed not to trust data that originates outside the script. As the data is not trusted—it's “tainted”—Perl won't let you use the data in an unsafe way without raising a run-time exception.

I can turn on Perl's tainting technology by changing the first line of my CGI script to include the taint mode switch:

#! /usr/bin/perl -wT

When I reload the fiddled-with URL, the resulting HTML page is empty and Apache's error_log has been appended with an insecure dependency error. This is Perl's way of telling me that the script failed due to tainting errors. Obviously, with the script failing in this way, it is no longer a security threat to the system. However, it also is no longer doing what it was designed to do, which makes it all but unusable. To make the script usable again, we need to untaint the input data using Perl's regular expression technology. The idea is straightforward: by defining a pattern representing safe data, the pattern can be applied to the tainted data and—assuming the pattern matches—any results are untainted and considered safe. With the CGI script, there are two data inputs, query and title. I added the following regular expressions to the CGI script to untaint the input data:

$query =~ /^([-\w]+\.sql)$/; $query = $1; $title =~ /^([\w:.?! ]+)$/; $title = $1;

The first regular expression matches on a string that has any combination of hyphens or word characters, followed by a period and the letters s, q and l. Anything else doesn't match and is considered suspect. If a match does occur, Perl remembers the match in the $1 match-variable, which then is assigned back to the now untainted $query. With titles, the pattern allows any combination of word characters and those characters included within the square brackets of the regular expression. Again, the $title variable is untainted when a successful match occurs.

As the CGI script executes an external executable—namely, the MySQL client—the environment's path also needs to be untainted. This is accomplished by setting the PATH variable within the environment to a safe list of directories, as follows:

$ENV{'PATH'} = "/usr/bin";

With these changes made to the runquery.cgi script, it is usable once more. As well as being quick-and-dirty and safe from user tampering, my solution is no longer a potential security threat to my system.

To link my simple reporting interface into my Soccer Club application, I changed the custom/frontpage template to include an additional list item that refers to the reporting Web page:

<ul>

[% FOR table = config.display_tables %]

<li>

<a href="[%table%]/list">Work with the

[%table %] data</a>

</li>

[% END %]

<li>Work with the <a href="Reports.html">

Reports System</a>

</ul>

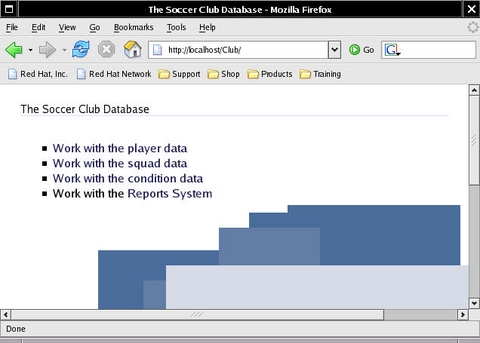

When the application is loaded into a browser, the link appears as part of the initial Maypole menu, as shown in Figure 4. My Web-based reporting system is simple, safe and easily extended. All I need to do now is write some more SQL queries.

Paul Barry (paul.barry@itcarlow.ie) lectures at the Institute of Technology, Carlow, in Ireland. Information on the courses he teaches, in addition to the books and articles he has written, can be found on his Web site, glasnost.itcarlow.ie/~barryp.