At the Forge - Sunbird and iCalendar

When I first started to write server-side software, I laughed at the thought that I was writing applications. After all, I was writing only small bits of code; nothing I did could hold a candle to what a real program, running on the desktop of someone's computer, could do.

Of course, things have changed quite a bit in the computer industry since those early days. Today, Web-based applications are not only an established fact of life, but they seem to be playing an increasingly prominent role in our daily lives. Recently, I began to look into software that I could use to prepare my US income taxes. I shouldn't have been surprised to discover that many companies now are offering Web-based tax calculation programs. The term ASP, or application service provider, was hot several years ago, when it seemed as if all software would work over the Web. Although there have been some obvious success stories, there also were many failures, for technical and business reasons alike.

It's easy to understand why Web-based applications are attractive to a business: you no longer have to test your software on every platform but instead only on a handful of browsers. You no longer need to support many different versions of the software, because only one version is accessible at any given time. Bug fixes and software updates can be integrated into the system almost continuously. The software is available from anywhere with an Internet connection, instead of only on the computer on which it was installed. The list goes on and on. From many perspectives, this approach makes more sense than stamping out thousands of CDs, testing the software on hundreds of configurations and staffing a large call center to support all of those configurations.

But for all of the hoopla, Web applications still are limited compared to their desktop counterparts. Because all serious processing is done on the server, including writing to and reading from databases and files, instantaneous feedback from the interface is almost impossible. Even with the fastest servers and a lot of clever magic, such programs still can seem somewhat tedious. Google's new maps system (see the on-line Resources), for example, demonstrates that it is possible, albeit difficult, to create Web applications that feel much like their desktop counterparts.

Those of us without Google's resources increasingly are turning to another solution, namely using hybrid software—desktop applications that rely heavily on Web technologies. It used to be that Web technology could be described, with a fair degree of precision, as HTML-formatted documents retrieved by way of HTTP using a URL. Web browsers were, for a long time, the only programs that made serious use of these standards.

Today, however, a growing number of desktop programs make use of HTML, HTTP and URLs, even though they aren't Web browsers. They use URLs to locate remote resources, HTML for its simple, universally understood method of creating hyperlinked documents and HTTP because it is reliable, simple, universal and cacheable. There aren't too many examples of word processors and spreadsheets using these protocols—at least, not that I'm aware of—but one hybrid program has been playing an increasingly prominent role in my life, Mozilla Sunbird.

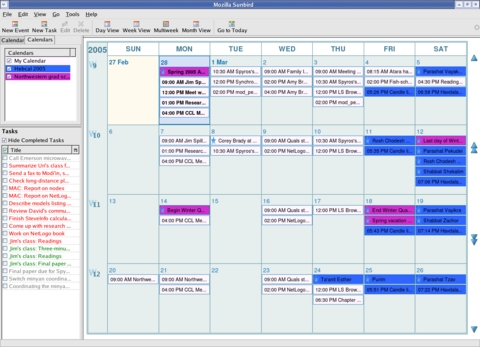

Sunbird (Figure 1) is the standalone version of the calendar extension that can be installed along with either Firefox or Thunderbird. Integration with these two programs is far from perfect, and I sometimes want to run or restart one without the other. So I installed Sunbird over the summer and have been pleased with each new release as it is made available.

Figure 1. The main Sunbird window, in multiweek mode. Two of my three calendars (Hebcal 2005 and Northwestern grad school) are color-coded, both in the definition pane and the main window. Also notice how items in my to-do list are color-coded, indicating whether they are on time, late, in need of attention or ongoing.

Now, you might think there is nothing inherently useful about having a calendar use Web technologies. But in the case of Sunbird and the iCalendar standard, there is a major benefit—namely, the ability to create calendars for public consumption. This month, we begin a several-month journey through the creation, distribution and sharing of calendars based on the iCalendar standard. Along the way, we'll see not only how to work with iCalendar, but how the hybrid applications can provide a powerful combination of features and an enhanced user experience.

iCalendar is an Internet standard for sharing calendar information across different computers. The basic idea is simple: if everyone at my office keeps track of their schedules on their own computers, it makes things efficient for those individuals but no better for the group than if everyone were using a pocket diary. Scheduling meetings still would be a hassle. Moreover, group events would have to be entered once on each person's calendar—meaning that when a meeting moves from Monday to Wednesday, each of the people on the team needs to adjust their individual calendars accordingly.

iCalendar was designed to solve this problem by standardizing the calendar files themselves such that those files can be transferred from one program to another. The original vision, as far as I can tell, pictured everyone using programs that implement iCalendar on their computers and sharing that information with others by way of the network and Internet. The reality has taken some time to catch up with this theory, but a variety of programs now are available that do implement parts of the iCalendar suite.

I should note that the entire iCalendar Project has been the victim of some bad and unlucky naming problems. The file in which data is stored and that can be used to interchange information is called vCalendar, just as the electronic business-card format is known as vCard. But many people and applications, including Sunbird, refer to the file format as iCalendar, even though the file identifies itself as vCalendar. As you can imagine, the term iCalendar has been shortened to iCal, which is especially unfortunate, given that Apple's Mac OS X operating system comes with a program called iCal that uses the vCalendar file format. Because the use of vCalendar to describe these files seems to have gone the way of the dodo, I simply use the word iCalendar to refer to both the file format and the overall standard.

Download and install the appropriate version of the Sunbird standalone calendar program; see Resources for the URL. If you're a bit more daring, you can install one of the nightly builds; I actually am using Sunbird as my primary calendaring application, so I have been using the official builds. If you prefer to have your calendar integrated into either Firefox or Thunderbird, go to the main download page and choose the appropriate extension and version that you would like to install. If you install an extension to Firefox or Thunderbird, you need to restart the host program before continuing.

Sunbird allows you to create two types of items, events and tasks. Events normally appear on the calendar itself and can include holidays and meetings. Tasks normally appear on the left side of the screen and indicate things that you should get done, with an optional starting and ending date. Sunbird changes the color of tasks according to how soon they need to be done; overdue tasks are in red, current ones are in blue and future ones are in green. Gray tasks are in the far-off future, and crossed-out ones—if you choose to display them—are completed tasks.

Both events and tasks can be repeating, meaning we can schedule a meeting for every Wednesday at 4 pm over the next ten weeks rather than entering ten individual events in the calendar. We can enter exceptions to such recurring events as needed, and we can set them to recur every few days, months or years, with “every few” being user-definable.

The way in which Sunbird structures these events and tasks strongly mirrors the vCalendar files in which they are stored. Although you might expect a modern Internet standard to use XML, iCalendar's file format consists of name-value pairs separated by a colon (:). Each event or task has its own begin or end line, and the entire calendar file similarly is nested between overall begin and end lines. Normally, each name-value pair in an iCalendar file sits on a single line. However, indenting a line with any whitespace means that it continues the data from the previous line, as in:

name:value name2: value2 name3 :value3

The above example defines three name-value pairs, each making slightly different use of whitespace. Sunbird normally uses the third option, such that each name is on a line by itself with its associated value indented on a subsequent line. Sunbird, as with other Mozilla products, puts all of its data files in a profile directory whose name is created randomly when you first start the program. The iCalendar files themselves are placed in the Calendar subdirectory within the profile directory.

The beauty of iCalendar is you aren't expected to have all of the calendar data in one file or even on one computer. An iCalendar-compliant program displays the union of all calendar data from all of the data files it has been instructed to read. You thus can have several different calendar files on your own computer, each of which reflects a different aspect of your life, for example, personal vs. professional. You also can retrieve calendar data files from other sources, including over HTTP, meaning that group calendars can be stored on a public server but displayed on your own computer.

When you first start Sunbird or when you first create a calendar with it, the program creates a CalendarDataFile.ics file. If you have more than one calendar, you end up with a number of such files on your system. Each file has the name CalendarDataFileN.ics, where N represents the number of the calendar you have created.

The structure of the file itself is pretty simple. For example, here is an iCalendar file with a single event, namely this month's Linux Journal deadline:

BEGIN:VCALENDAR VERSION :2.0 PRODID :-//Mozilla.org/NONSGML Mozilla Calendar V1.0//EN BEGIN:VEVENT UID :05e55cc2-1dd2-11b2-8818-f578cbb4b77d SUMMARY :LJ deadline STATUS :TENTATIVE CLASS :PRIVATE X-MOZILLA-ALARM-DEFAULT-LENGTH :0 DTSTART :20050211T140000 DTEND :20050211T150000 DTSTAMP :20050209T132231Z END:VEVENT END:VCALENDAR

As you can see, the file begins and ends with VCALENDAR declarations. Each event is surrounded by BEGIN:VEVENT and END:VEVENT. Each event then has a unique ID; a summary, which normally is displayed in the calendar; a status; a class, which indicates whether you want to share this calendar information with others; and then the starting and ending times. It also has a timestamp showing when the event was last modified.

Timestamps in iCalendar files adhere to a slightly strange format of YYYYMMDD representing the date and then a T followed by the 24-hour clock time, followed by an optional time zone and a Z. Because I currently am living in Chicago, the timestamp represents not the time at which I made the entry, but the time it is in the time zone six hours ahead of me, one hour later than GMT (1Z).

What happens if I have a monthly deadline, and I want to include that in this calendar event? In Sunbird, I can go into the recurrence tab in the event editor by double-clicking on the event. There, I indicate that I want this event to repeat once every month, which changes the interface such that I'm now asked if it should be on the 11th of every month—that is, on the same date—or on the second Friday of every month, relative to the month. If I choose the first, my iCalendar file looks like this:

BEGIN:VCALENDAR VERSION :2.0 PRODID :-//Mozilla.org/NONSGML Mozilla Calendar V1.0//EN BEGIN:VEVENT UID :05e55cc2-1dd2-11b2-8818-f578cbb4b77d SUMMARY :LJ deadline STATUS :TENTATIVE CLASS :PRIVATE X-MOZILLA-ALARM-DEFAULT-LENGTH :0 X-MOZILLA-RECUR-DEFAULT-UNITS :months RRULE :FREQ=MONTHLY;INTERVAL=1 DTSTART :20050211T140000 DTEND :20050211T150000 DTSTAMP :20050211T132231Z LAST-MODIFIED :20050211T153505Z END:VEVENT END:VCALENDAR

Notice how a RRULE property has been added, with values of FREQ=MONTHLY and INTERVAL=1. You might imagine that if I were to change this deadline to be every two weeks, it would be FREQ=WEEKLY and INTERVAL=2. This is true, except that it also adds a BYDAY=FR field, indicating that the event happens on Fridays.

If I choose to make this event occur on the second Friday of each month, the iCalendar file looks like this:

BEGIN:VCALENDAR VERSION :2.0 PRODID :-//Mozilla.org/NONSGML Mozilla Calendar V1.0//EN BEGIN:VEVENT UID :05e55cc2-1dd2-11b2-8818-f578cbb4b77d SUMMARY :LJ deadline STATUS :TENTATIVE CLASS :PRIVATE X-MOZILLA-ALARM-DEFAULT-LENGTH :0 X-MOZILLA-RECUR-DEFAULT-UNITS :months RRULE :FREQ=MONTHLY;INTERVAL=1;BYDAY=2FR DTSTART :20050211T140000 DTEND :20050211T150000 DTSTAMP :20050211T132231Z LAST-MODIFIED :20050211T153824Z END:VEVENT END:VCALENDAR

Notice how our RRULE property now is FREQ=MONTHLY, because this happens every month, with an INTERVAL=1. Also notice that BYDAY=2FR has been added, meaning that the event takes place on the second Friday of each month.

Finally, let's take advantage of Sunbird's ability to have remote calendars by moving this file out of our directory and onto another system. I move the CalendarDataFile7.ics file, which was so named because it was the seventh calendar I created, to /tmp. I then copy it to my Web site so it can be available at the URL https://reuven.lerner.co.il/CalendarDataFile7.ics. I double-check that the file is available from this URL by trying to download it using wget. When I see that it works fine, I know I can put this information into Sunbird.

Now I go into Sunbird and delete the ATF calendar; Sunbird won't let you remove the filename of an existing local calendar. I then choose subscribe to remote calendar from the File menu, and enter the URL at which I have placed my .ics file. Once the calendar has been downloaded, I see the LJ deadline event on my calendar each month, exactly as if it were on my local machine. And in fact, if you look in the Calendar directory, you can see that the file is on your local machine. It has been downloaded and installed into that directory, and it can be refreshed whenever you request. Simply right-click on the calendar name and select reload remote calendar).

Our investigation of hybrid desktop-Web applications has begun with an examination of the iCalendar/vCalendar file format, using the Mozilla standalone Sunbird application. We were able to create different types of events and then move the resulting iCalendar file from our local machine to a remote server.

However, our calendar is static, meaning that someone has to modify it by hand or by uploading a calendar file each time it changes. In my next column, we will learn how to create iCalendar files dynamically, using a Web/database application. We then will look at different ways in which calendars created on one computer can be written to a server and shared with other people.

Resources for this article: /article/8128.

Reuven M. Lerner, a longtime Web/database consultant and developer, now is a graduate student in the Learning Sciences program at Northwestern University. His Weblog is at altneuland.lerner.co.il, and you can reach him at reuven@lerner.co.il.