Cooking with Linux - Lights...Camera...Action!

I'm afraid it's true, François. The camera does not lie. That's what you look like when you are serving wine. Of course, mon ami, I have no intention of putting this little video on our restaurant's Web site. Why am I doing this? Ah, you have not yet looked at the feature for today's menu. Multimedia and entertainment is the ticket, mon ami, and you have to admit, this little video certainly is entertaining. Don't be upset, François, I have the ultimate respect for you. Besides, there's no time to fret, our guests will be here any moment. Ah, you see, they are already at the door.

Welcome, mes amis, to Chez Marcel! It's wonderful to see you all today here at the finest Linux restaurant on the planet, which also happens to be the home of one of the greatest wine cellars in the world. Please sit and make yourselves comfortable. François was just heading to the wine cellar now. The 2001 Santa Lucia Highlands Pinot Noir is drinking very nicely. It's a showy wine, bursting with hints of stardom—perfect for today's menu.

As you will notice, each workstation today is equipped with a small Webcam and microphone. The immediate idea is that we (or someone else) will wind up as the star of our little movie, but sometimes the software itself is the star. After all, many an application has shone on Chez Marcel's menu, non? And, this is where Karl Beckers' xvidcap comes into play. xvidcap is a great little tool for recording the action on your X desktop using a program called ffmpeg, which likely is already on your system. The result is an MPEG movie of your entire desktop or any portion thereof.

Why would you do such a thing, you might ask? Well, you can use this to create a training video to show others how to use an application or to show the world how good you are at playing your favorite first-person shooter. To get your copy of xvidcap, head on over to the official Web site (see the on-line Resources). The site offers both source and some binary packages, such as RPM or DEB. Should your particular distribution not be covered, building xvidcap from source is a simple extract and build five-step:

tar -xzvf xvidcap-1.1.3.tar.gz cd xvidcap-1.1.3 ./configure make su -c "make install"

The program name is either xvidcap or gvidcap. I say either because if you have the GTK2+ development libraries (version 2.2.1 or later), you get a second binary. Both work the same but, quite honestly, the GTK2+ interface looks and works better. If you don't have a recent GTK2+, you still may be able to get the interface by using one of the binary packages as opposed to source.

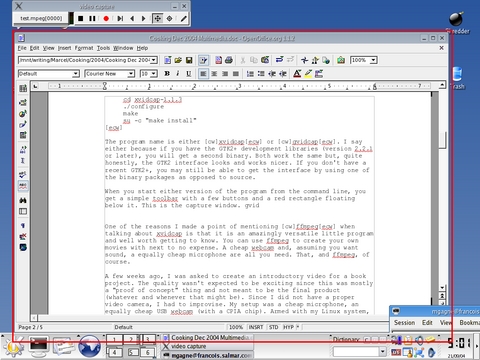

When you start either version of the program from the command line, you see a simple toolbar with a few buttons and a red rectangle floating below it. This is the capture window, and you can move it to cover whatever area you want to record. The default window, however, is fairly small. To change the area you want to record, click the crosshairs icon (second from the right on the toolbar), then click and drag the pointer to take in whatever area you want to include in your capture. The red rectangle will be resized. The toolbar contains buttons to record, stop, pause and so on. Pausing over the buttons will display tool tips. That's it, you are recording a movie of whatever transpires inside the red rectangle (Figure 1).

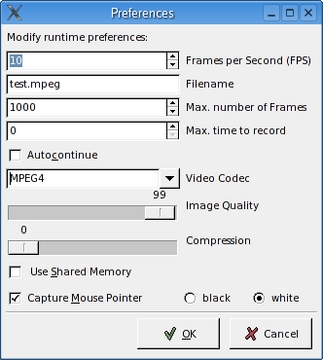

Some preference settings let you change the number of frames per second, the video codec and whether you want to capture the mouse pointer in the final video. Right-click on the frame button (first on the left) and select Preferences (Figure 2). After you've experimented for a while, type man xvidcap for details on running the program without the GUI. The added bonus is that you can capture audio as well, which is perfect if you are creating an instructional video.

One of the reasons I made a point of mentioning ffmpeg when introducing xvidcap is that it is an amazingly versatile little program and well worth getting to know. You can use ffmpeg to create your own movies with next to no expense. A cheap Webcam and, assuming you want sound, an equally cheap microphone are all you need (and ffmpeg, of course).

A few weeks ago, I was asked to create an introductory video for a book project. The quality wasn't expected to be exciting, because this was mostly a proof-of-concept thing and not meant to be the final product. Because I did not have a proper video camera, I had to improvise and thereby created what might well be the world's cheapest video recording studio (Figure 3). My setup was a cheap microphone and a cheap USB Webcam with a CPIA chip. Armed with my Linux system, I figured I was ready to go. The only question was “How?”

Using ffmpeg, I created my video clip, experimented with timing, frame rate and so on, until I had something that was getting pretty good. With the following command, I created an AVI format video clip at ten frames per second:

ffmpeg -vd /dev/video -ad /dev/sound/dsp -r 10 \ -s 352x288 video_test.avi

That's it. My video device input (indicated by the -vd option) is /dev/video and my sound, or audio, input was /dev/sound/dsp. That's the -ad option. Your own devices may be a little different of course. For instance, on another of my machines, the USB video device is /dev/video0. As it stands, the command continues to record until you run out of disk space. So, to limit a recording to ten seconds, I use the -t option:

ffmpeg -vd /dev/video -ad /dev/sound/dsp -r 10 \ -s 352x288 -t 10 video_test.avi

The resulting clip, which I called video_test.avi, can be played with Xine, Kmplayer, MPlayer or whatever video player you prefer.

Well, mes amis, my foray into video production on the cheap was a success, or so I thought. When I sent the video clip for approval, I was asked whether they could have it in MPG format instead. Rather than redoing what obviously was a great work of cinematography, I converted it using the following command:

ffmpeg -i video_test.avi video_test.mpg

As versatile as ffmpeg is, you certainly should spend a few minutes looking at the man page. I promise you'll discover a lot of really cool uses for it.

For those of you who already own a digital video camera, recording high-quality video is not a problem. The challenge is to get the video on your hard disk for editing, compressing and eventually burning to disk for sending to friends and family. I have a Sony Handycam. It comes with a USB port, but it also has a much faster means of getting the video transferred through a high-performance serial bus or, as most people know it, a FireWire port. The real techies out there refer to it as an IEEE1394 port. Your computer also needs to have such a port (or card) in order to transfer the information, but the performance of the IEEE1394 port truly is worth the investment.

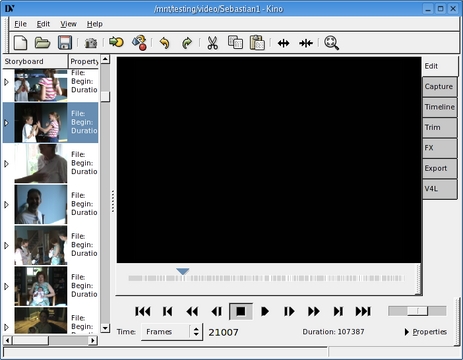

To manipulate the resulting video in a friendly way, however, you need to get your hands on a video editor like Arne Schirmacher's Kino (see Resources). The dvgrab program, also available from the Kino Web site, is built-in to Kino so you don't need a separate copy. You see, mes amis, like xvidcap, Kino uses a few command-line tools under the pretty interface. One of those tools is our old friend ffmpeg.

These days, Arne has some great developers working on the project, and they have put together a rather nice and easy-to-use video editor for Linux. See the feature article on page XX. The beauty of Kino is that you can use it to extract and edit video directly from your IEEE1394-compatible video camera. If you have such a device, which can be connected with a FireWire cable, Kino even lets you control the device through the application. Before I continue on, let me step back and say something about the IEEE1394 support. Any recent Linux distribution should have IEEE1394 support included (through loadable kernel modules), but on my test system, the drivers weren't loaded automatically. No problem—I loaded them manually:

modprobe ohci1394 modprobe raw1394 chmod 666 /dev/raw1394

Getting your digital video across the IEEE1394 cable and onto your computer can be done easily from the command line with dvgrab. After all, that's what Kino does to capture video. Although you can type dvgrab and start capturing, the best way to do this is by using the -i option, meaning interactive. You then can control the camera and capture using simple single key presses.

dvgrab -i Going interactive. Press '?' for help. q=quit, p=play, c=capture, Esc=stop, h=reverse, j=backward scan, k=pause, l=forward scan, a=rewind, z=fast forward, 0-9=trickplay, <space>=play/pause Capture Started

We become accustomed to working with graphical interfaces, but this is a lot easier and nicer to use than it sounds. The resulting video file on your system is called dbgrab-XXX.avi by default, the XXX being a three-digit extension.

Kino's interface is clean and easy to navigate (Figure 4). To the right of the main window, tabs indicate the various functions, from capturing to editing to exporting the finished product. The Edit tab is where most of the work happens (after the Capture, of course). This is where you cut or join scenes, or even insert additional files in to your video project. The Timeline tab breaks up the current scene (and video clip) into multiple frames, so you can jump to any part of the video without having to play the whole thing.

An FX tab lets you add various special effects to your videos. These include things like reverse video, sepia tones, mirror and kaleidescope effects and so on. Audio effects include fade in, fade out and silence.

Once you start truly enjoying your digital video camera, you are going to record more than a few minutes of tape. The reason I mention this is that when you are capturing output from your digital camera with Kino, a number of large files will be created, each about 820MB in size and each sequential for the duration of the video. Those mega-files aren't what you want your final product to be, however. That's what the Export tab is all about. Various options are available here (in a group of sub-tabs) including exporting only the audio tracks to WAV files. I also like the fact that I can export stills of individual frames. The option I tend to use the most, however, is DV pipe, and this is where ffmpeg makes an encore appearance.

After all the editing, cutting and pasting is done, I export my finished product using ffmpeg to either video CD AVI files or DVD format. The resulting files (for example, VCD AVI format) are much smaller and much more manageable. One hour of digital video takes up about 9GB of disk space. The exported video, however, fits nicely on a single 700MB CD-ROM.

As you can see mes amis, your Linux system provides some great tools to make you, or your software, a star. Speaking of which, it seems as though closing time has arrived already and judging by the wine-induced smiles on some of your faces, we have the opportunity to capture some memorable video. I jest, of course. François, do be so kind as to refill our guests' glasses one more time. Perhaps what we should capture for posterity is our parting toast. Until next time, mes amis, let us all drink to one another's health. A votre santé Bon appétit!

Resources for this article: www.linuxjournal.com/article/7808.

Marcel Gagné (mggagne@salmar.com) lives in Mississauga, Ontario. He is the author of the all new Moving to the Linux Business Desktop (ISBN 0-131-42192-1), his third book from Addison-Wesley. In real life, he is president of Salmar Consulting Inc., a systems integration and network consulting firm. He is also a pilot, writes science fiction and fantasy, and folds a mean origami T-Rex.