Cooking with Linux - Performing at the Speed of Light

You are right, François, computers and operating systems have come a long way. Not only do we have the good fortune to be running the operating system of the future today, but we can take advantage of machines that are faster than ever before. I remember with some, well, I hesitate to call it fondness, but I do remember my first x86-based PC. It was a turbo-charged XT with a processor that ran at 10MHz. I also spent a small fortune upgrading its RAM from 640K to 1,024K by plugging a couple of dozen chips in to IC slots on the main board.

Quoi? Of course not, mon ami, although that stuff was fun at the time, I would not give up the technology of today. That almost would be like giving up Linux for another operating system. You know, François, it's interesting to think about exactly how far we have come—from megahertz to gigahertz processors in only a few short years! Where will we end up in another ten years? I suppose that faster than the speed of light may be possible, though I fear it may take somewhat longer, mon ami. Still, you have given me an idea.

Mon Dieu! Our guests are here already. To the wine cellar, immédiatement! Head to the north wing and check behind that new shipment of Bordeaux wines Henri delivered yesterday. You'll find a few cases of 2000 Châteauneuf-du-Pape. Forgive me, mes amis. Please sit and make yourselves comfortable. François and I were discussing how far technology has come in the last few years. My faithful waiter brought up the idea of faster-than-light computing, certainly the ultimate in high-performance computing, this issue's theme. Even if we could have computers delivering information at beyond light speed, we still would need to absorb information at our own pace. One thing is for sure, we wouldn't see the stars zipping by as we read the latest on-line Linux Journal column.

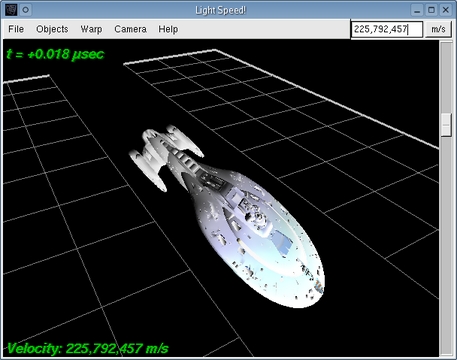

In terms of high performance, nothing beats the speed of light, at least not without some strange matter or access to a matter/anti-matter engine and some dilithium crystals. You can get that feeling by firing up your screensaver and selecting rocks if you are using xscreensaver or the OpenGL space in KDE's own list. How objects look as you approach the speed of light is a popular mainstay of science-fiction films, but generally speaking, we never get to see what it actually might look like. That was the inspiration behind Daniel Richard G.'s Light Speed!, a program designed to show precisely what happens to our view of an object as it approaches the speed of light. The program takes into consideration various relativistic effects, such as Lorentz contraction, red/blue Doppler shift, headlight effect and optical aberration. The About page on the Light Speed! Web site describes all these effects (see the on-line Resources).

Mes amis, you are sure to enjoy this wine—truly high-performance strength, dark fruit flavors, a hint of coffee and mocha and a long finish. Enjoy it while we crank up the speed a bit. The build is very easy. You should be aware that you need the OpenGL or Mesa development libraries loaded as well as the gtkglarea libraries. From there, it's a simple extract and build five-step:

tar -xzvf lightspeed-1.2a.tar.gz cd lightspeed-1.2a ./configure make su -c "make install"

Start the program by running lightspeed. You should see a window appear with a three-dimensional lattice cube. In the upper right-hand side, an input box lets you enter a speed in meters per second. Start with something fairly high; you also can use the up and down arrow keys to increase or decrease speed with finer control. When you press Enter, the object is accelerated to that speed with the resulting effects shown in the graphical window.

A cube getting distorted as it approaches the speed of light is only so interesting, although you can create a more complex lattice by clicking File on the menu bar, selecting New Lattice and choosing the number of points in three dimensions. The real question on my mind is what happens to a spaceship as it approaches the speed of light? Luckily, the Light Speed! Web site also has an objects download feature that you should pick up too. It contains three additional objects, including a model of the starship from Star Trek Voyager (Figure 1). To use a different model, click File and select Load Object.

One of the more interesting things you can do to extend this bit of educational fun is to head over to the 3-D Cafe (see Resources), where you will find a lot of three-dimensional models and meshes to try. Don't limit yourself to spaceships, though; a race car approaching light speed also is fun to use. Keep in mind that only models with a 3DS (3D Studio) or LWO (LightWave 3D) extension work with this feature.

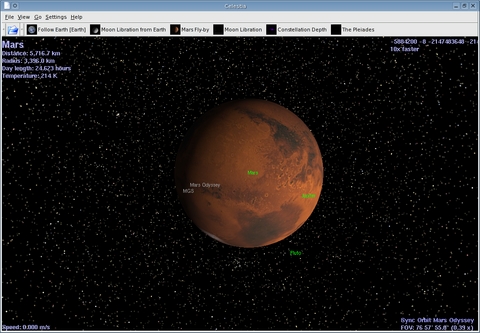

As much fun as it is to imagine what really happens under these conditions, what we all really want to do is go flying through space at warp ten while the stars zip by, arriving at some distant world before we can empty another bottle of wine. For just such a trip, get your hands on Chris Laurel's Celestia. With Celestia, you can tour around our solar system, visit over 100,000 different stars, check out what's happening with various Earth-launched spacecraft and much more. Source is available on the site, but there are binaries for Mandrake and SuSE and others also are available. If you can't find binaries for your distribution, never fear. Because this is an OpenGL project, you need the 3-D libraries, but the build itself simply is another extract and build five-step:

tar -xzvf celestia-1.3.1.tar.gz cd celestia-1.3.1 ./configure make su -c "make install"

To run the program, call celestia from the command line or your command launcher. You need to know about a few keystrokes right now, because they make the experience that much more fun. Pressing the letter L accelerates time by a factor of ten. Doing so puts your travel through space in motion relative to whatever object you have chosen as your point of reference. Pressing K decelerates time, should you start going a little too fast. Pressing Alt-C brings up the Celestia browser from which you can select objects of many flavors. At the bottom of the screen are four radio buttons. Click the With planets button, and a list of stars with known planets appears. Want to visit the planet orbiting 51 Pegasi? Right-click on the object's name, select Goto and strap yourselves in for a faster-than-light trip to this alien world. Once there, right-click on the star, 51 Pegasi, select Follow and you can watch the planet's orbit as you remain focused on the star.

Keystrokes also let you specify the representation of stars, from tiny pinpricks to fuzzy points to scaled discs. To find out what all the keystrokes do, click Settings on the menu bar and select Configure Shortcuts.

Celestia is a great program to sit back and explore and is well worth the download. Aside from stars and planets, you can visit spacecraft currently orbiting nearby worlds, such as the Mars Global Surveyor. Try heading for the spacecraft, click on Mars and then select follow (Figure 2). Now accelerate time. A number of major asteroids also are in the database if you'd prefer a trip to Eros.

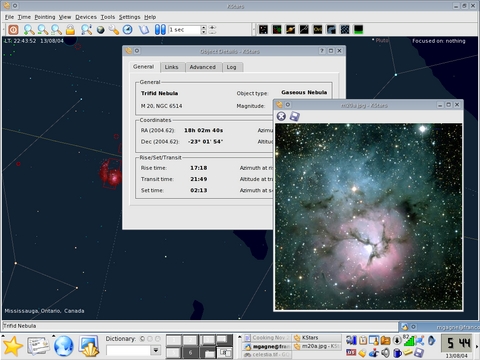

If zooming through space at or exceeding the speed of light is enough to turn your stomach not to mention your face a few shades of green, then perhaps a more down-to-earth space-based approach is in order. Why not observe the stars and planets from the comfort of your non-moving seat? The best way to do this is with a great program called KStars, originally created by Jason Harris.

KStars is a desktop planetarium program that displays the locations of stars and planets on your desktop. Because KStars is a part of the KDE desktop environment—included in the kdeedu package—you don't have to look far to get a copy. You can find the latest on the package by visiting the Web site.

KStars is amazing fun but much more than a toy. With a database of the planets, 130,000 stars, 13,000 deep-sky objects, the planets and many asteroids, KStars is an astronomical treasure. With it, you visually can identify the position of stars, galaxies, nebulae and other glories of the night sky. You can control what is displayed, zoom in on objects and—I love this part—download images from on-line resources, such as the Hubble and the Space Telescope Science Institute. Simply right-click on an object of interest, and the pop-up offers you additional information and links to high-resolution images of those objects when appropriate. Figure 3 shows my KStars session pulling up information on the Trifid Nebula.

When you start KStars, it assumes your location is Greenwich, United Kingdom, which probably is not what you want. Start by clicking Location on the menu bar and selecting Geographic. A dialog box will appear with a world map. Click an area on the map close to where you live. Doing so provides you with a list of geographical points in a list to the right of the map. Make your selection and click OK. Should you happen to know your latitude and longitude, you can enter that at the bottom of the window instead.

KStars includes much more than what I can cover in this short visit. For instance, KStars can control your telescope, locating and tracking objects. Furthermore, if you are into astro-photography, KStars can control CCDs, currently supporting Finger Lakes Instruments devices with others in development.

Mon Dieu! Although it may not have happened at hyper-light speeds, it certainly has happened fast. Yes, I'm talking about the clock, mes amis, which already is telling us it is closing time. With talk of moving so quickly, it is at times like this that we can truly appreciate sitting back under a starlit night, slowly sipping a little more of this excellent Châteauneuf-du-Pape. Until next time, mes amis, let us all drink to one another's health. A votre santé Bon appétit!

Resources for this article: /article/7753.

Marcel Gagné (mggagne@salmar.com) lives in Mississauga, Ontario. He is the author of the all-new Moving to the Linux Business Desktop (ISBN 0-131-42192-1), his third book from Addison-Wesley. In real life, he is president of Salmar Consulting Inc., a systems integration and network consulting firm. He is also a pilot, writes science fiction and fantasy, and folds a mean origami T-Rex.