Cooking with Linux - François, Can You Keep a Secret?

It really is a shame François, but we simply will have to make sure it is available for next time. Everything else looks perfect, mon ami; all the workstations booted up to a login. Wonderful! Ah, I see that our guests are here! François, head down to the east wing of the wine cellar. There is a small cache of 1999 Côte-Rôtie next to that old sealed-in door. Yes, the door we never were able to open. Vite, François! I promise you there is nothing frightening down there.

Please sit, mes amis. We have an almost perfect menu for you today, but sadly it's missing one item. Still, the Côte-Rôtie Rhône, red that is both sexy and mysterious, should help take away from its absence. I had so wanted to prepare my famous Crème Linuxaise for you today, but there were problems. You see, the Linuxaise is an old and secret family recipe, and I could not risk it falling into the wrong hands. Nor could I risk sending it by e-mail for fear of it being intercepted or read by a network sniffer; otherwise, François could have prepared it in advance. It is that secret!

Next time, however, will not be a problem. I am setting up all users at the restaurant with GnuPG and public key encryption so that sensitive communications can be sent without fear. GnuPG is the GNU Privacy Guard, a program that makes it possible to encrypt messages and data in general. It is a patent-free, open-source replacement for PGP (Pretty Good Privacy). A number of Linux e-mail packages allow you to send and receive encrypted e-mails using GnuPG, and this is what I'd like to show you today. Most modern distributions have GnuPG included, so if you don't have it on the system, check your CD first. You also can find the latest version at www.gnupg.org, but first, a little background.

Now, where was I? Ah, yes. Historically, all encryption methods worked on the premise of a shared key file. You would give the person with whom you wanted to communicate the same key by which the message was encoded. Think secret decoder ring and you aren't far off the mark. The catch is that anyone intercepting the key then could decipher all your messages. With GnuPG, messages are encrypted with two keys, one being your private key, which you guard jealously and never hand out to anyone. When I encode a message, I do so by combining my private key with a public key, not my public key, but one supplied to me by the person with whom I want to communicate, François, for instance. Both keys are required for the encryption/decryption process, and anyone having one-half of the key pair has nothing, which is why you never hand out your private key. To get in on this top-secret action, you need to create a key pair, containing both your private and jealously guarded key and your public key, the one you hand out to all your friends. Here is the command:

gpg --gen-key

What follows is a small question-and-answer session. The first question has to do with the encryption algorithm, or cipher. The default is DSA and ElGamal. Accept the default. When asked about key length, you can choose from 768, 1,024 and 2,048 bytes. Because the DSA standard is 1,024, choose that for now. Then, you are asked for the expiration date of your key, the default being no expiration date. You can, however, define days, weeks, months and even years. For now, choose the default and confirm your choice. Finally, you are asked to supply the name of the key user, the e-mail address and a comment.

It's all over but the passphrase, which is your final step. Make sure you choose something secure but also something that you can remember. When you have entered your phrase, the GnuPG program generates your secure key pair. After the command completes its work, you can verify the result by looking in the .gnupg directory in your home directory:

$ cd /home/marcel/.gnupg $ ls gpg.conf pubring.gpg random_seed secring.gpg trustdb.gpg

The gpg.conf file contains a list of default options for the gpg command and makes for good reading. The pubring.gpg and secring.gpg files are particularly important. Make backups of these files immediately and store them somewhere other than your computer and never lose them—the secring.gpg file contains your personal secret key. The last file, trustdb.gpg, is your database of trust. It defines the level of trust that you assign to the public keys you collect.

Users need to exchange keys in order to exchange encrypted information. As you might guess, the option to export a key is --export, but you may want to include the -a option as well to confine the output to ASCII format:

gpg -a --export 3E2FCF7D > marcelkey.asc

The resulting file is a simple ASCII text file; how you get it to the other person is up to you. There are key servers where you can upload your public keys so that anyone can download them (which makes it easier for large-scale distribution), key-signing parties where groups get together and exchange public keys or e-mail attachments. The recipient then could import the key like this:

gpg --import marcelkey.asc

At any point, you can choose to see the keys in your key ring with:

gpg --list-keys

The results of that command depend on how many keys you have, but the following should give you an idea of what to expect. In particular, take note of the hexadecimal number following the 1024D. That is the key ID to which you will be referring in the future:

/home/marcel/.gnupg/pubring.gpg ------------------------------- pub 1024D/3E2FCF7D 2004-01-07 Marcel Gagné ↪(Writer and Free Thinker at Large) <mggagne@salmar.com> sub 1024g/B24717BE 2004-01-07 pub 1024D/EE392B87 2004-01-07 Francois ↪(I am but a humble waiter) <francois@salmar.com> sub 1024g/F4E07040 2004-01-07

Before you can start your friend's key to encrypt e-mail messages, you need to sign the key to verify its authenticity. This involves doing two things. If you are absolutely, positively sure of the key's origins, you might skip the first step, which is to get the key's fingerprint:

$ gpg --fingerprint francois pub 1024D/EE392B87 2004-01-07 Francois ↪(I am but a humble waiter) <francois@salmar.com> Key fingerprint = 8C5B 775C 33F8 E97C 5ADC ↪019D C6C8 4B83 EE39 2B87 sub 1024g/F4E07040 2004-01-07

Notice that I used the person's name in the above command, which is part of the key information. If you have more than one person with that name in their key information, specify the key ID instead. To verify this fingerprint, ask your friend to check the fingerprint of his or her personal key in exactly the same way. The final step is to sign the key. You do that with the --edit-key option:

gpg --edit-key francois

The whole process isn't too complicated. You are asked to confirm that you really, genuinely want to sign this public key; you are asked to confirm again with your passphrase. You need to do this with all the people with whom you want to exchange encrypted e-mail. Once finished, however, let the secret messages flow.

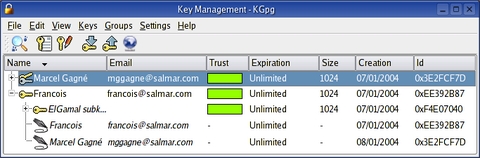

Incidentally, a number of nice, graphical utilities for GnuPG exist, essentially friendly wrappers for the command-line utility. KDE comes with a slick utility called KGpg that integrates nicely with the desktop and the e-mail system. For instance, if someone sends you a public key as an attachment in KMail and you have started KGpg (command name: kgpg), rather than having to save the attachment to a file, drop down to the command line and perform the above steps. You should get a friendly pop-up like the one in Figure 1.

Figure 1. KMail confirms key imports.

With this tool, which docks in your panel, you can edit keys; add, remove and change trust levels; and do all those things you can do with command-line GnuPG but with a click of your mouse. You even can do key server lookups over the Net and use photo IDs as well. Its integration with other KDE tools means you can drag and drop to encrypt or access GnuPG functions with a click from Konqueror or the clipboard. KGpg is an add-on to KDE 3.1, but with the release of KDE 3.2, it will become part of the standard distribution. Figure 2 shows KGpg in action.

Another graphical administration tool worth your time is gpa. This is the default GNU Privacy Assistant and the official key ring editor of the GnuPG Project. It also is available from www.gnupg.org.

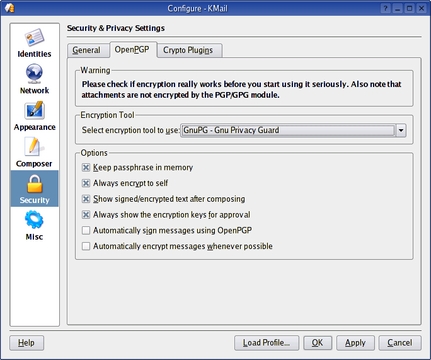

Now, it's time to send out those encrypted e-mails. Open KMail, click on Settings in the menubar and choose Configure KMail, after which the Configure KMail dialog appears. In the sidebar to the left, find the icon labeled Security, and click it (Figure 3).

The new window to the right has three tabs: General, OpenPGP and Crypto Plugins. We are interested in the OpenPGP tab. On that tab, look at the drop-down box labeled Select encryption tool and choose GnuPG - GNU Privacy Guard from the list. For the time being, don't choose to sign and encrypt all messages automatically. You might, however, want to keep the passphrase in memory; you still are asked the first time an encrypted message is encountered. Click Apply.

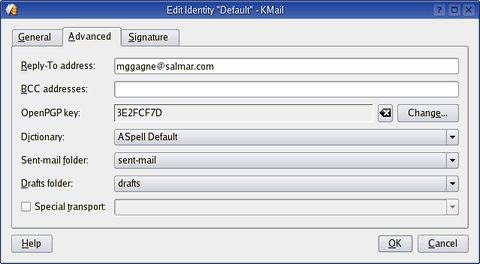

Next, click on the Identity tab to the left. Unless you have defined multiple e-mail identities, there should be only one entry. Click Modify, and select the Advanced tab from the resulting dialog. In the middle of that panel (Figure 4) is a space for OpenPGP key. That's your personal private key. Click Change here to open another window from which you can select your private key information.

When finished, click OK to close the Edit Identity window, and click OK again to close the Configure KMail window. In order to reload the keys into KMail properly, you may have to shut down KMail and restart it.

You now are able to send encrypted e-mails, in principle at least. If you already have your friend's public key in your key ring and you have signed the key, nothing is left to do but write your e-mail. Start a new message, and write what you need to write. When you are ready to send, click Options on the message's menubar. Notice two interesting options here related to encryption. One says Sign Message, and the other says Encrypt Message.

Signing a message makes use of your key by attaching an electronic signature to your message but not encrypting it. The person receiving the message then has a means of verifying that the message did indeed come from you, should they want to verify it. Because the message is not encrypted, anyone still can read it. This is simply a means to confirm that the message came from the person who claims to have sent it. Encryption goes one step further in that you are using your friend's public key to encrypt the message. In both cases, KMail asks you for your passphrase before sending the message.

Unfortunately, not all e-mail packages follow the same rules for encryption. That would be too simple, non? Let's use the two gentlemen at table 17, Larry and Michael, in a hypothetical scenario. Each needs to send the other sensitive corporate information, so the information must be encrypted. Larry uses Evolution and Michael uses KMail. We already have covered KMail for sending encrypted mail, so let's spend a moment looking at the process in Ximian Evolution.

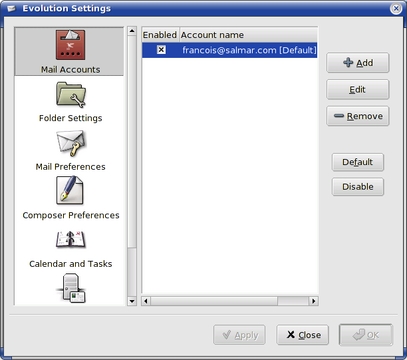

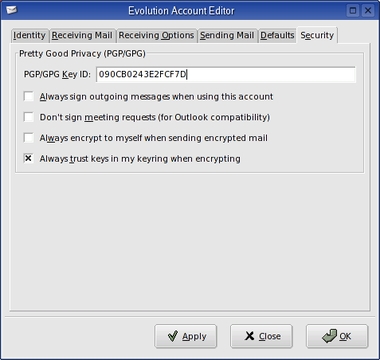

With Evolution open, click on your inbox. Now, click Tools on the menubar and select Settings. You now are looking at the Evolution Settings window (Figure 5). If the Mail Accounts icon in the left-hand sidebar isn't selected, click to select it now. Most people have one main account. If you have more than one, select the one you want to use with encryption and click the Edit button to the right. The Account dialog appears with several tabs along the top. The one you are interested in is labeled Security. Look for a field labeled PGP/GPG Key ID and enter your key ID there. Click OK to close that dialog, then OK again to get out of the Evolution Settings window.

Assuming that Larry and Michael already have exchanged public keys, Larry now is ready to send encrypted e-mail. To do so, he composes an e-mail normally. When he is ready to send, he clicks Security on the menubar and selects PGP Encrypt. When he clicks Send, Larry is asked for his GPG passphrase. Once entered, the message is sent. Before I move on, I should mention that you can select PGP Sign from the Security menu if all you want to do is sign the message.

As wonderful as all this encryption and decryption stuff is, there are some problems. For instance, many packages (including KMail) will encrypt the message in-line, but a few others, such as Evolution, do not. Instead, encrypted messages are MIME attachments. Consequently, reading a message from KMail (or Eudora or Outlook) in Evolution requires that you save the message as a text file. You then can decrypt it with this:

gpg -d message.txt

To read an Evolution-encrypted message sent to KMail (and a few others) you need to save the attachment as opposed to the message itself. Decrypting it is the same process as above.

Many e-mail clients are available in the Linux world. KMail and Evolution are popular graphical choices, but so is Mozilla. For users of Mozilla, a plugin called Enigmail allows for seamless encryption and signing of messages. Text-based clients also support encryption, either on their own or through plugins; mutt and pine are popular examples.

Mon Dieu! Has the time gone by so quickly? I fear, mes amis, that closing time is upon us once again. François will refill your glasses once more before you go. As you leisurely sip that last glass, take some time to create and exchange public keys with one another. Perhaps I may be convinced to share the Crème Linuxaise with some of you—assuming proper security precautions, of course. Who knows, our security may be the very reason that door in the wine cellar remains tightly shut! Until next time, mes amis, let us all drink to one another's health. A vôtre santé! Bon appétit!

Resources

Gnu Privacy Guard (GnuPG): www.gnupg.org

KMail: kmail.kde.org

Mozilla: www.mozilla.org

Mozilla Enigmail: enigmail.mozdev.org

Ximian Evolution: www.ximian.com/products/evolution

Marcel's Web Site (check out the wine page): www.marcelgagne.com

Marcel Gagné (mggagne@salmar.com) lives in Mississauga, Ontario. He is the author of Moving to Linux: Kiss the Blue Screen of Death Goodbye! (ISBN 0-321-15998-5) from Addison Wesley. His first book is the highly acclaimed Linux System Administration: A User's Guide (ISBN 0-201-71934-7). In real life, he is president of Salmar Consulting, Inc., a systems integration and network consulting firm.