Linux Lunacy 2003: Cruising the Big Picture, Part II

Our first port of call was the most unlikely looking capital city in the country, or perhaps anywhere. It's not even a city; it's a small collection of plain buildings squeezed between docks and cliffs at the bottom of a fjørd. The high school is as big as the capitol building. No roads lead in or out--if you want to leave town, you're taking a plane or a boat. But be careful. The airport is notoriously windy and dangerous for pilots unfamiliar with its peculiar conditions. And the harbor can get clogged up with the same cruise ships that provide the town's primary source of revenue.

But adversity breeds high degrees of competence, and there's no shortage of that, in either aviation or boating, in the Juneau Linux Users Group (JLUG). The JLUG members graciously volunteered to share "brats & beer", show us around town and demonstrate what Alaskan hospitality is all about.

We were greeted right off the boat by Bill Arnold (with the free beer), Jamie Brown and Fritz Funk (holding the sign). The three gents hauled about ten of us out to Jamie's hillside house, which looks straight down the airport runway. There we talked about all kinds of local, national and intergalactic Linux and geek stuff.

I was impressed especially with what the elders of the Juneau LUG tribe do for the younger generation. Fritz, retired from the Forest Service, works with young people on all kinds of projects involving the resurrection and rehabilitation of old computers. Fritz also is a pilot who home-schools his eleven-year-old son Joe (also a pilot) in the air as well as at sea.

We got an interesting education in a short time just by hanging out with these guys. (And we were treated to some of the best smoked porter I've ever tasted.)

[Note to selves: We should introduce these guys to Steve Roberts, who lives on Camino Island in Puget Sound. He introduced Linux Lunatics to his Linux-powered Microship when he spoke on board the M.S. Maasdam two Lunacies ago.]

After plowing through lunch at Jamie's house (the spread was excellent and went way beyond bratwurst), our hosts hauled us out to Mendenhall Glacier, which has been in retreat in recent years. Rocks that haven't seen daylight since the Pleistocene are appearing through the face of the advancing ice. Those of us with adequate footwear hiked over to a spectacular waterfall that used to land on the glacier, but now cascades down to sea level.

After the LUG guys dropped us off in town, a few of us took the tram up Mt. Rogers. From our elevated perspective, we could see how the four biggest buildings in town had hulls. We were too late to hike around (and the instructions for dealing with bears discouraged half-mile hikes into the tundra at sundown), but we did get to witness a perfect Alaskan sunset before we headed back to the boat. Most of the rest of the Lunatics still were out on one of Neil's legendary pub crawls.

While exploring the colder reaches of the Pacific in 1778, Captain James Cook and his men got a break in the weather and observed the highest coastal mountains in North America. Cook gave the name Fairweather to the range and to its tallest peak. On board were future captains William Bligh (later of the Bounty) and George Vancouver. When Vancouver returned with Joseph Whidbey to explore the same coast in 1794, the pair named and mapped Icy Straight at the south end of the range. Vancouver described the source of the strait's frozen hazards--a five-mile indentation in the coastline--as "a compact sheet of ice as far as the eye could distinguish".

That was at the end of the Little Ice Age. The Earth has warmed since then. Today that same sheet of ice has retreated sixty-five miles, exposing the full length of Glacier Bay, one of America's most remote and spectacular national parks.

For me the day started early, around 2am, when my sister woke me up and told me to go out on deck and look at the sky. At first I thought I was seeing clouds in the moonlight, but then I saw their shapes change. They stretched and shrank, disappeared and reappeared again, shifting in color from gray to greenish with hints of red. I'd waited more than 56 years to see the aurora borealis--the northern lights--and here they were.

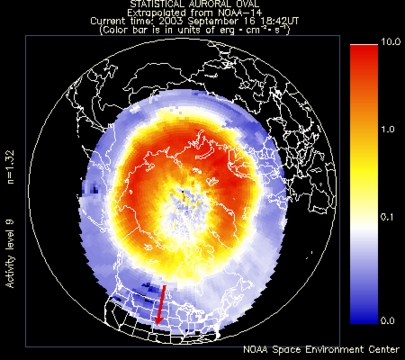

After watching the show for awhile, I came inside, checked the Auroral Activity page and found that we were right under the halo of luminosity that surrounds the north magnetic pole. I also saw that the solar wind pushes the halo around, sometimes as far south as San Diego, Texas and North Carolina. The image below was produced later in the same day by data from a POES polar orbiting satellite; the red arrow points toward the Sun. To gauge your own chances of catching the show this winter, check the Kp maps at the Space Environment Center's Viewing Tips page. For readers Down Under, it shows south polar conditions too.

[Note: I'm writing this on October 24, while a solar windstorm is raging. Watch Solar Terrestrial Dispatch for details, reports and forecasts of aurora displays at lower latitudes.)

We began moving north up the bay at sunrise, after a shore boat loaned us a ranger from park headquarters. Over the ship's public address system, the ranger explained that most of the land exposed by the retreating glacier had been buried under ice for at least the last 20,000 years. And because the glacier had evacuated the bay in only 200 years, the bare land it left behind served as an excellent laboratory for the study of pioneering and maturing plant and animal communities.

We could see plant succession at work as we sailed North up the bay. Mature hemlock forests gave way to younger and smaller trees (some turning to fall colors), followed by meadows thick with Sitka alder. As we neared the bay's branched sources, each with its own glacier, we watched the ecosystem grow younger. Plants became smaller and more sparse, until finally only the most primitive life forms coated the rocks and grew out of crevices beside the glaciers themselves. The Park Service explains how the system reveals itself:

Plant recovery may begin here with no more than "black crust", a mostly algal, felt-like nap that stabilizes the silt and retains water. Moss will begin to add more conspicuous tufts. Next come horsetail and fireweed, dryas, willows, alder, then spruce, and finally hemlock forest. In many areas the final or climax stage of plant succession may be the boggy muskeg, but this may take hundreds of years to develop, after the establishment of hemlock-spruce forest.Where plant's seeds happen to land can be critical. The chaotic rock-and-rubble aftermath of a glacial romp is deficient in nitrogen. Alder and dryas are important pioneers because they improve the soil by adding nitrogen to it... Sitka alder begins to form dense entanglements that are the bane of hikers. Spruce takes hold and eventually shades out the alder. A forest community is begun. Each successive plant community creates new conditions.

I began to think of plant succession as a useful metaphor for the growth of Linux and open source in the ecosystem of information technology. I also began to see Glacier Bay's rapidly fading Ice Age as an equally useful metaphor for the waning years of the Industrial Age.

Before I left Seattle, some friends there gave me a copy of Emile Zola's The Ladies Paradise (Au Bonheur des Dames), which describes the birth of modern retailing at Paris' large new department stores, which were the first in the world. The Bon Marché was born in 1853. The Louvre followed in 1855, and the Printemps in1883, the year of the book's publication. The Sam Walton of that time was Aristide Boucicault, who turned Bon Marché from a small retail store to a factory for the distribution, display and sale of wares, the production and pricing over which he enjoyed unprecedented control. Here's Kristin Ross from the introduction to The Ladies Paradise:

(Boucicault) initiated a number of startling practices designed to accelerate sales that would soon become the virtual commandments of commerce in Second Empire department stores. Boucicault was the first to bring an enormous variety of goods under the same roof, and he was the first to apply fixed prices to the merchandise. (Laws passed in the last decades of the ancien régime had forbidden retailers from displaying fixed prices.) He could also be called the inventor of "browsing"; passersby could, for the first time, feel free to enter a store without sensing an obligation to buy something. Goods were rotated frequently, with a low markup in price; high volume and frequent rotation created the illusion of scarcity in supply among what were in fact mass-produces and plentiful goods. Departments within the store increased dramatically in number; the illogical design of their layout served to increase customers' disorientation...

Thus, a new culture of commerce began as another one ended.

The old agrarian regime protected the public marketplace where people met to trade goods and make culture. In the new industrial regime, the meaning of marketplace shifted from real to abstract. Markets now were product categories, demographic groups and appetites for manufactured goods. Craftspeople displaced by industrial automation found new work serving as human parts of industrial machines. The marketplace was nothing more than a conceptual region where supply satisfied demand.

As Horatio Alger taught, success for individuals in the Industrial Age came not from overcoming The System but from rising up through it. After several generations passed, nobody remembered what life was like when your surname (Baker, Hunter, Marchant, Tanner, Weber) derived from your craft and your work was your own.

Like Alaska's glaciers, the industrial system pioneered so successfully by Boucicault is in retreat but is far from gone. For example, we still understand business largely in terms of shipping and retailing. Our language betrays those mental presets when we speak of moving goods through a value chain or of delivering services and experiences. Closer to home, it remains customary to assume that nearly all Good Things in the technical world come from manufacturers, distributors and vendors. This in spite of the fact that no company in any of those categories can lay legitimate claim to a starring role in the success of the Net or Linux, no matter how often or how prominently analysts and press put the Big Names up on the marquee.

The real stars were individuals and groups whose achievements were to create a new system -- one in which the demand side supplies itself. That's the story Paul Kunz told the night before, about the role of high energy physicists in the creation of the Net and the Web. It's also the story of Linux, Apache, Python and every other member of the LAMP suite.

"Networked markets get smarter faster than most companies", Chris Locke said. That's why, according to Netcraft, about 65% of all Web sites are now hosted by Apache, and the trend continues in an upward direction. Self-supply--scratching your own itch--is a development method that dates to the dawn of human intelligence, one that continued quietly throughout the Industrial Age.

What finally started melting industry's glaciers was the Net. And that's because they came to rely, unavoidably, on the Net as an environment for business. All the world's large companies today repose on the Net's infrastructure. In many cases, they contribute to the components of that infrastructure, including Linux and the whole LAMP suite. In other words, they too operate on the demand side of the marketplace.

Although Linux and LAMP are handy as can be, they have not established themselves fully in the habitats left bare by the retreating glaciers. Watching the rocky shore go by in Glacier Bay, I decided that we are somewhere between the horsetail and alder stages of plant succession in the marketplace. We will know the marketplace has reached maturity when everybody once again feels free to ply and sell their talents and crafts, with or without the assistance of large industrial manufacturers, distributors and retailers.

So that's roughly what I said in my keynote that evening, titled "Fortune 500 Domination: How Linux is Establishing a Healthy Businessphere". I told the story of plant succession in the marketplace, of how Linux is helping lead the world out of the Little Ice Age of industry-dominated thinking and commerce and of how I believe that the computer industry will resemble the construction industry when it's through maturing.

I pointed out that construction is the largest and oldest industry in civilization, that it has no single dominating vendor, that it subordinates sale value to use value, that it believes commodities are good things, that it finds ways to live with margins under 80% and that it makes room for everybody. (We also already borrow heavily from its vocabulary--we architect, design and build things like platforms and structures using tools, for example--so the transition shouldn't be too big a sweat.

I also talked about how the press gets it wrong when it insists, constantly, that Linus is in some kind of gladiator match with Bill Gates of Microsoft. If you follow both guys at all, you realize after awhile that the fight is entirely one-sided. That is, it's only being fought by one side. The other side doesn't even care. So, playing off Linus' book Just for Fun, I imagined that an equivalent book by Bill would be titled Just for Fight.

Which philosophy, I wondered, would be more viable in the new businessphere?

Doc Searls is Senior Editor of Linux Journal, covering the business beat. His monthly column in the magazine is Linux For Suits, and his bi-weekly newsletter is SuitWatch.

email: doc@ssc.com