New Projects - Fresh from the Labs

People interested in sharpening their mental faculties in an environment that is genuinely challenging would do well to give this a go. According to gbrainy's Web site:

gbrainy is a brain-teaser game and trainer to have fun and to keep your brain trained. It provides the following types of games:

Logic puzzles: games designed to challenge your reasoning and thinking skills.

Mental calculation: games based on arithmetical operations designed to prove your mental calculation skills.

Memory trainers: games designed to challenge your short-term memory.

Verbal analogies: games that challenge your verbal aptitude.

gbrainy provides different difficulty levels, making gbrainy enjoyable for kids, adults or senior citizens. It also features player's game history, player's personal records, tips for the player, or fullscreen mode. gbrainy also can be extended easily with new games developed by third parties.

Installation

For those chasing binaries, packages are available for Debian, Ubuntu, Fedora, SUSE, Mandriva, One Laptop Per Child and NetBSD. Also available is the obligatory source tarball, and for those who want to run the bleeding-edge version, you can grab it using git. I won't be covering how to run git here, but nevertheless, I will incorporate git users into a line of my instructions. As usual, I'm going with the source tarball.

Here are the library requirements, according to the gbrainy Web site:

intltool 0.35 or higher.

Mono 1.1.7 or higher.

GTK and GTK Sharp 2.8 or higher.

librsvg 2.2 or higher.

Cairo 1.2 or higher.

Mono.Addins 0.3 or higher.

And, also according to the Web site, for a standard Ubuntu installation, the packages required for compiling gbrainy are intltool, mono-gmcs, mono-devel, libmono-dev, libgnome2-dev, libgnomeui-dev and libmono-cairo2.0-cil.

Download the latest tarball, extract it, and open a terminal in the new folder. If you've downloaded the development git version, before carrying on, enter:

$ ./autogen.sh

For everyone else, simply enter:

$ ./configure

If your distro uses sudo:

$ sudo make install

If your distro doesn't use sudo:

$ su # make install

Note that compilation doesn't seem to require the use of make. Once the installation is finished, run the program with the command:

$ gbrainy

Usage

Once you're inside, using gbrainy is pretty straightforward. The GUI layout and design are excellent, along with many other functions, such as text input, difficulty settings and so on. gbrainy even has a special setting to adjust for the color blind. Starting out in gbrainy is obvious. There are buttons for testing the following subjects: Logic, Calculation, Memory, Verbal or All (for taking every subject at once).

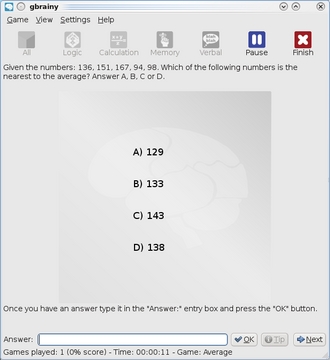

gbrainy presents you with challenging mathematical problems that often test your spatial abilities alongside arithmetic.

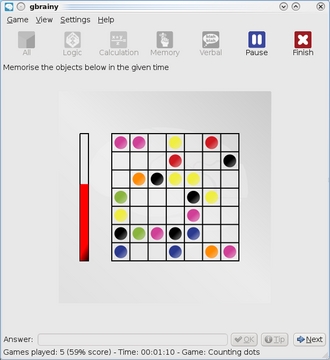

In the Memory tests, you'll find yourself using different ways to memorize things from what you may have done previously, especially when you're given such a short time limit.

As each test starts, bear in mind that most questions aren't in the realm of “mildly taxing”. Even on the default medium setting, most of these questions are quite tricky. It quickly will become apparent which subjects you have a knack for and which you'll struggle with.

Logic uses puzzles, such as number and block sequences, grid layouts and so on, generally for guessing the next number or arrangement in a sequence.

Calculation typically has you guessing for the closest number to something, using very thought-intensive divisions, multiplications, averages and so on, that seem to move beyond basic arithmetic skills.

Memory introduces a time factor, so pay close attention. Things such as a series of directions, a grid containing different objects or words spelling out colors that are actually colored with something different (such as the word yellow colored blue) are shown on-screen for a very short amount of time, and you'll be asked about an individual element that's usually pretty hard to recall.

And finally, there's Verbal, which plays games like finding the odd word out, identifying the word most suitable for a given situation, choosing what word can be used in relation to a certain word pairing and so on.

Thankfully, the text input is very dynamic in that the developers have thought ahead about what possible combinations people may enter, so chances are if you enter something in a different case or some other kind of textual variation, the input accepts it or instructs you as to how to answer the question.

All in all, this is a very challenging package. I wouldn't be surprised if it becomes a mainstay of educational distros, but hopefully, it catches on in standard distributions as well.

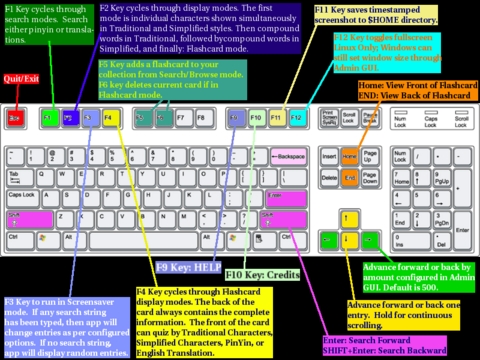

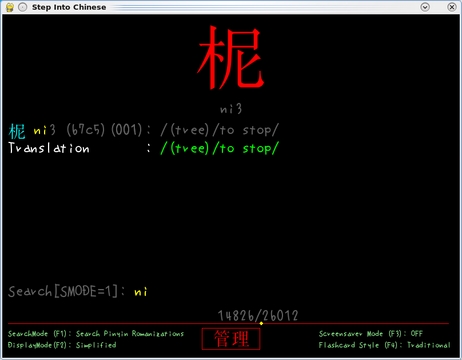

If you've been playing around with other flashcard systems trying to learn Chinese or perhaps running into problems with switching between Traditional Chinese, Simplified Chinese and Pinyin, this may be the project for you. To quote the Freshmeat page and parts of the Web site:

Step Into Chinese is a flexible language-mining and flashcard system to assist English speakers seeking to understand the Chinese language. It was designed to address the lack of a one-to-one correspondence between Chinese characters and corresponding Pinyin morphemes.

The lack of a one-to-one correspondence between Chinese characters and the corresponding Pinyin is often regarded as the greatest difficulty facing learners of Chinese. Step Into Chinese has been designed to address exactly this difficulty.

Inside is an extensively cross-referenced data structure that allows the user to pursue deeper understanding of contexts, for example, by “locking on” to a particular Pinyin context and viewing successive instances of the same morpheme used in similar contexts.

The user can also “lock on” to English words in the Pinyin translations, English words in the collective phrase translations, and even Unicode strings used to represent Chinese characters in either traditional or simplified representations. Frequency information relative to the number of occurrences of each Pinyin morpheme, in each context throughout the data structure, is displayed for each entry.

The application data structure contains over 26,000 modern Chinese words and concepts, corresponding to over 8,300 separate Chinese characters. Colors are used consistently throughout the application for rapid location and absorption of information.

Installation

Apologies for the long project URL above—you're probably better off just visiting the main page at new.asymptopia.org. Why this confusion? Well, Step Into Chinese (SIC) is part of a collection of software developed by Asymtopia Software, a grass-roots open-source development company. In order to download SIC, you first need to create an account at the Web site, but don't worry, it's “free and only to prevent excessive download abuse by non-humans”. It also allows you to participate on the Web site. I'm interested in several projects from Asymtopia and probably will be highlight them in the coming months, so you might want to go ahead and make an account now.

Before I go further, in terms of library requirements, you need to install the pygame libraries, which on my Kubuntu system were named python-pygame. As far as package options go, there seems to be only a .tar.gz file (no binaries), but don't fret, the installation is easy. Download the newest tarball, extract it, and open a terminal in the new folder.

If your distro uses sudo, enter:

$ sudo setup.py

If your distro doesn't use sudo, enter:

$ su # setup.py

From here, you can run the program with:

$ stepintochinese

Usage

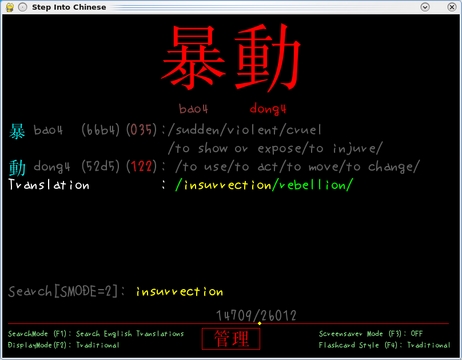

First, a screen displays the status of some postprocessing, which has to do with Pinyin morphemes and their usage contexts. This may take a minute, but let it be. Soon you'll be inside the main screen. To give you an idea how it works, SIC already will have a word entered (that word being hello) and in the process of being displayed in “screensaver mode”, where each English word is shown along with its Chinese translation in both Pinyin (Romanized letters) and Chinese characters, which can be set to either Traditional or Simplified.

Step Into Chinese allows you to look up English words in both Traditional and Simplified Chinese, as well as Pinyin.

You also can look up words in Chinese using Pinyin (Romanized letters); here I'm displaying a word in Chinese Simplified.

Now all this might be a bit confusing to take in at first, so let me break it down for you. The word hello will be on-screen, but you'll want to enter your own words to translate, so let's do that now. First, press backspace once, and screensaver mode (which I'll explain in a minute) will stop, allowing you to enter your own text. Now, keep pressing backspace until hello is gone, enter your own text, and press Enter. Your word now will appear in translated form above or at least a part of it in another English word (for instance, “car” may be inside “careless” or “carriage” and so on).

If the displayed translation isn't the one you want, press Enter again, and the next translation will be displayed. Keep pressing Enter, and you can scroll through all translated possibilities. Note that SIC accepts only American English. As an Australian and like most of the English-speaking world, I actually speak British English (this is an American publication; I don't normally spell this way), so entering something like “mum” or “colour” turned up with nothing. So if your entry doesn't produce any results, it might be that you're not using American English.

Let's move on to the screensaver mode. This is where the traditional flashcard system comes into place. Press F3, and all of the possible translation options will cycle through the display at a default rate of ten-second intervals. If you want to use SIC as a screensaver of sorts, pressing F12 puts SIC in full-screen mode.

As for Chinese characters, you probably will want to switch between Chinese Traditional and Chinese Simplified, so press F2 to do so for the standard display mode, and then press F4 for screensaver mode.

So far, I've dealt only with English text input, and SIC isn't restricted to that. You also can enter words in Chinese to display their meaning, albeit in the Romanized Pinyin form (actual Chinese text input is a much more complicated process in a non-Chinese OS setup, and this is aimed at foreign international users after all). Pressing F1 switches the search mode's parameters between English, Pinyin Chinese or Unicode searches.

That's about all I have space for this month, but ultimately, my time with Step Into Chinese has been a pleasant one. Although the interface is initially confusing, once you've been introduced to the basics, operating SIC actually is quite a simple process. I also like how the Asymtopia folks have shown some artistic flair in using fonts that are funky and colorful to make a pleasant working environment. SIC is highly recommended.

Brewing something fresh, innovative or mind-bending? Send e-mail to newprojects@linuxjournal.com.

John Knight is a 25-year-old, drumming- and climbing-obsessed maniac from the world's most isolated city—Perth, Western Australia. He can usually be found either buried in an Audacity screen or thrashing a kick-drum beyond recognition.