The Giant Zero, Part 0.x

Back in October, my keynote at New Media Days in Copenhagen was titled "The Internet: Not Just Another Medium". Although most of the talk was new, the core concept is was one I first presented at the Berkman Center three weeks earlier: that it helps to think of the Net as a "giant zero". Now that I've given the talk twice and thought about it for a month more, I'm almost ready to make the same case in text. So here goes:

1. The Net isn't a medium. It's a place.

Partly it's perception. The Net is something you go on, not thrrough. You look stuff up on the Net. You build stuff on it too. That's why it has addresses, locations, sites.

But what's its architecture? Its shape? Well, in reality it doesn't have one. Real as it may be, it's not solid, not physical. I'm not even sure it's virtual, because "virtual" implies unreal somehow; but the Net is very real. We relate to it as a real place.

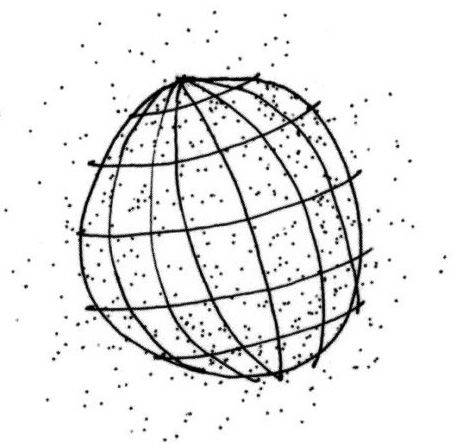

The metaphor I like best comes from Craig Burton, who first observed that a hollow sphere is the best geometrical characterization of an end-to-end network comprised of human and electronic peers that are all effectively zero distance from each other. (The concept was presented originally in End to End Arguments in System Design.) Here's how Craig put it in a 1999 interview for Linux Journal:

I see the Net as a world we might see as a bubble. A sphere. It's growing larger and larger, and yet inside, every point in that sphere is visible to every other one. That's the architecture of a sphere. Nothing stands between any two points. That's its virtue: it's empty in the middle. The distance between any two points is functionally zero, and not just because they can see each other, but because nothing interferes with operation between any two points. There's a word I like for what's going on here: terraform. It's the verb for creating a world. That's what we're making here: a new world. Now the question is, what are we going to do to cause planetary existence? How can we terraform this new world in a way that works for the world and not just ourselves?

In early 2003, David Weinberger and I called this conceptual sphere a "World of Ends", in a posted essay by that name (at worldofends.com). I still think that's a good way of describing it, but I also like The Giant Zero for several reasons.

First, nothing in a zero needs improvement. It's silly to say, "I'm going to get in the middle of this thing and improve it. This vacuum just doesn't suck enough." More importantly, a zero needs no mediation. It puts everybody, including The Media, on the outside. This doesn't mean The Media have no advantages, or that they can't help terraform the Net's world. It just means that their business isn't helping make the Net more of what it already is.

The carriers are in a somewhat different situation. Their job one they still haven't accepted is making the Net as "stupid" (as in empty, vacuum-filled, distance-free) as possible, even as they also work to improve the technology that makes this possible. The "stupid" label comes from David Isenberg, who wrote The Rise of the Stupid Network in 1997, while he was still at (the original) AT&T. The idea is not just to limit a network's duties to simply transporting bits, but to create a purely supportive infrastructure on which anything can be built stupid, that is, like the core of the Earth, on the surface of which we all live, as if it too were a giant zero.

This, by the way, is also what's meant by "net neutrality". The Net should be as neutral toward the bits it carries as Earth's gravity is toward everything that depends on it.

2. Distance is the main issue. Not bandwidth

The ideal perceived distance across any two points on the Net is the same as the one between your keyboard and your screen. You tap on the keyboard, and the results appear on the screen. Yes, there are delays there. But they don't matter. Nor does it make sense for anybody to charge a toll along the path between your fingers and your eyes. The functional distance, and the actual cost, are both zero.

In reality, of course, there are costs and delays in the way the Net actually works. But the ideal toward which we must work is one in which those costs and delays round down to zero.

3. The vacuum in the middle of the Giant Zero is sustained by light.

We can't help mixing metaphors when we speak of the Net's "backbone" and "trunks" of fiber optic cabling. But we can still sense the nature of the Net's zero-ness when we consider the friction involved in light that blinks in one end of a fiber optic cable and out the other. Even the most conductive wiring has some resistance to electrical current -- enough that you can detect that current with instruments. You can't do that with fiber optics. There is no physical difference between fiber optic cabling that's "dark" and cabling that's "lit".

Yes, it costs money to trench for cabling, to pull it through conduit and hang it from poles. But once the cable is installed, all the costs are at the ends. Unless the cabling is physically harmed, it just lays or hangs there, costing nothing. Unlike coaxial cable TV cable, or phone wiring, it isn't obsoleted by any imagined demands. Fiber capacity is that large. More importantly, it support endless possibilities for value creation. By anybody. Anywhere. With anybody else. Anywhere.

4) The Net is pure infrastructure.

As with the land and oceans Earth beneath our butts, the Net's primary role is supportive. It's a world whose supportive nature makes everything else possible. We cannot do without it.

Wikipedia calls infrastructure "interconnected structural elements that provide the framework supporting an entire structure". The Net is surely that, but as with oceans and land it is also also much more.

The deep and fundamental nature of the Net's infrastructure is a hard concept for people to get their heads around, when they're used to looking at the Net as an extra charge on their cable TV or phone bills. But in the long run video and telephone will just become breeds of data. Once the Net's light-based infrastructure is fully built out, it's as naturally costless as the crusts and oceans and the Earth.

5) The cost of building out the Net is secondary to its benefits.

Estimates for building out fiber to premises in most towns range up to $2000 per connection. But once the connection is there, and the resident is on the Net, the benefits of that connection are incalculable. There is no good way to calculate the unknown heights to which the Net's tide will lift the boats it floats.

Still, this is the place where many arguments come up. Who's going to pay for building out FTTx (Fiber To The Whatever)? If we borrow the money, how do we pay it down? Do we want to write off billions of dollars in the carriers' sunk capital expenses? Don't the carriers have the right to charge for using their "pipes", which are their property? How can we think this infrastructure is going to get built out, or improved over time, if there's no profit to be made by the businesses doing the science and the work?

Most of those arguments assume that the main (or only) benefits of incumbency for carriers come from charging for use of the "pipes". In fact, there are countless advantages for incumbents as alpha inhabitants of this new Earth's surface. There are services to create and sell. There are millions of existing customer relationships. There is physical real estate and office space out the wazoo. There are rights of way. There are support services to sell to persons and companies that build businesses on top of the Net's infrastructure. Why not get into those games as well? Why not look toward those games as motivation for building out the raw infrastructure?

The simple reason is that phone companies come from telephony and cable companies come from cable TV. They can't help thinking in terms of those businesses, and working to protect and leverage those businesses. That's why they fight those who appear to threaten those businesses. But at some point they'll stop doing that, and start taking advantage of this:

6) The Giant Zero is built to support an infinitude of business.

When the non-physical distance between everything in the world becomes zero, there's no limit to what you can do with that fact. This should be good news for anybody with imagination and entrepreneurial spirit. (Not to mention an equally endless variety of non-business possibilities.) Especially for businesses that already have advantages in their marketplaces. As phone and cable companies certainly do. They need to stop thinking of their corner of the Net as their private silo, and start thinking about the zillions of businesses that become possible, faster, with their help. And how they can make money in a wide-open and much bigger marketplace.

7) The Net is a public utility, like electricity, gas, water, waste treatment and roads.

Of course, there are costs of maintaining and improving the Net as a utility. We just need to appreciate the abundant lack-of-distance the Net is made to provide. By its nature the Net is less scarce -- once it's installed -- than other utilities.

8) We need to understand The Because Effect, and how it explains the real value of pure infrastructure.

The Because Effect happens when you make more money because of something than with something. For example, Google makes more money because of Linux than with Linux. Or because of search than with search.

With the Net, we have a because/with ratio that yearns toward the infinite. The more distance we get out of the Giant Zero, the more supportive it becomes. And the more money we make because of it than with it.

9) The Live Web is branching off the Static Web.

If you go to Google Blogsearch, you'll face two buttons. One allows you to "search blogs" and the other to "search the Web". The former delivers Live Web results. The latter delivers Static Web results from Google's familiar basic search engine.

Why does Google make that distinction? I think it's because there is not only a radical difference between the two kinds of search, but also between the natures of what they search.

The Static Web is the familiar one we describe in the static language of real estate and construction. We have sites that we architect, design and build. They have addresses and locations. We look for traffic to navigate its way through our facilities. This is the Web that Google and Yahoo index and search. It's the one that holds still long enough for the search engines' bots to index everything.

The Live Web is the one that we write and publish and put up and edit and syndicate and feed. It's the one that Google Blogsearch and IceRocket and Technorati index when they hear the pings that are the pulses of blogs, photo collections, news services, retailers and everybody else who exerts a living presence on the Web. Time-to-index with some of these services is under a minute. Sometimes only seconds pass between a blog post and a search result that includes that same blog post. "Rivers of news" are an example of how independent developers and users are terraforming the Net's giant zero. Dave Winer created the River of News concept many years ago, and gave it fresh relevance to hand-held Web browsers through bbcriver.com and nytimesriver.com, which flow fresh news items down simple html pages that are especially suitable for viewing on Blackberries, Treos, Nokia 770s and cell phones with Web browsers. In the course of an IM session this week, David Sifry created a subject-based river that flows news from New Media Days. The index page is myne.ws ('MyNews'), a new service allowing anybody to set up rivers form single sources (newspapers, magazines, blogs), multiple sources (e.g. favorites) or subjects (fed by syndicated keyword and/or tag search results). While it's still in alpha, it's a demonstration of how "live" the Web can get.

10) On the Live Web, immediacy matters more than mediation.Immediacy supports conversation and relationship, as well as transaction.

11) Works of art, good or bad, are not commodities. Nobody writes (or draws, or shoots, or sculpts) cargo.

When we talk about "content" all the time, we package out the fecundity of creative power, on the part of all the artists who work we de-characterize.

12) There's a new economy coming together around The Live Web.

It's the same as the old economy, only networked.

In the new networked economy, power isn't re-distributed. It's re-originated.

It originates with those who converse and relate, and not just those who transact.

13) In the Live Web economy, the value chain is replaced by the value constellation. There are only stars here.

Those stars are independent individuals who can contribute to whatever they please, provided they bring value. This is the mash-up economy, in which everybody needs to be open to possibilities in a market ecosystem that obsoletes silos.